HISTORY[]

Marsupials are the first of the two great groups of therian (live-bearing) mammals, distinguished by their tendency to expel the embryo from the womb at a very early stage, and then nurse the infant externally while it develops. The clade in which they are part of, the metatheres, originated in the Early Cretaceous, possibly in North America, and then spread around the globe. Today, marsupials are most numerous in Australia , where almost every mammal belong to that order. They also exist in great numbers in South America and some dwell in Eurasia and North America.

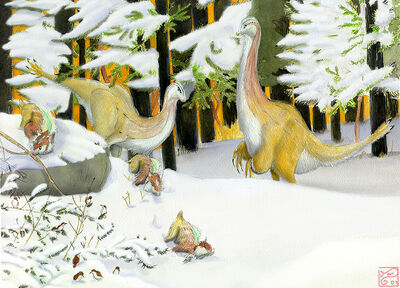

For the most part, Spec's metatherians are normal, diminutive Spec mammals, but this rule of thumb is not always followed. The Pliocene and Pleistocene brought with them massive environmental changes that did much to loosen the dinosaurs' hold on terrestrial niches. The Ice Age replaced the forest and jungle of the dinosaur world with tundra and steppe, driving many clades to extinction and opening opportunities to others.

The oceans were also open for colonization by mammals, and the otter-like selkies and each-uisges have made full advantage of this habitat, even going so far as to push the dinosaurian hesperornithians out of many of their niches over the course of the Neogene.

NESODELPHIA (Malagasy 'possums')[]

SUCHOTHERIIDAE (Selkies, Selters, Jarrks and Each-Uisges)[]

These primitive metatherians are otter-like, with stumpy legs and long, flexible bodies, but possess large conical teeth more similar to crocodilians than those of any mammalian group. They range across the Arctic oceans, in both freshwater and saltwater environments, eating fish and (in some species) larger game. Unlike their pinniped counterparts, however, suchotheriids lack insulating blubber, and so grow dense coats of fur to keep them alive in the frigid water that are their home. Selkies keep their fur water-repellent by producing oil from a preen gland (rather like that of a duck) and spreading it over their bodies.

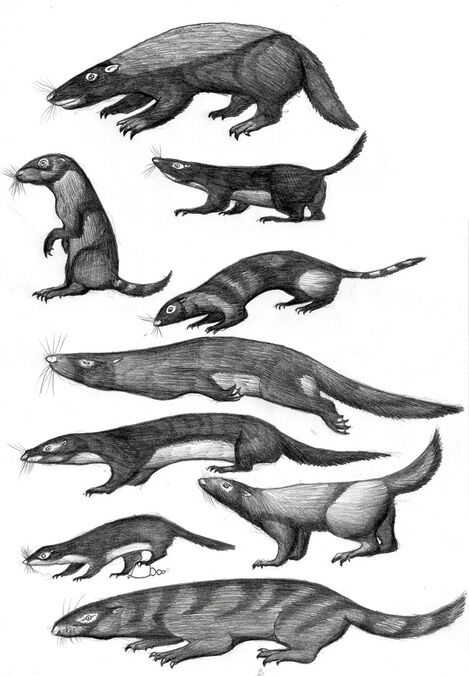

From their general morphology and from a few scant fossils, suchotheriids seem to derive from the very base of the metatherian family tree. Their dentition, having been adapted for the use of fish-catching, tells us little about their ancestry, but the selkies are probably derived from small, weasel-like carnivores such as Deltatheridium, which inhabited Asia during the Cretaceous. Eocene fossils show that these little carnivores were quite widespread during the Paleogene, and inhabited a wide number of niches. It was not until the Miocene, however, that we begin to find fossils that can be reliably ascribed to Suchotheriidae.

As marsupials, suchotheriids cannot give birth to their young in the water, as walduks or RL cetaceans do. A mother selky comes to shore to give birth to her single, fetus-like baby, which crawls from the womb into an insulated pouch on the belly. While her baby is in this pouch, the female cannot enter the water, and so she depends upon the infant's father, who either must catch fish for her to eat, or transfer the baby into his own pouch. The portion of time spent between mother and father varies widely between selky species, although there is little physical variation in a species.

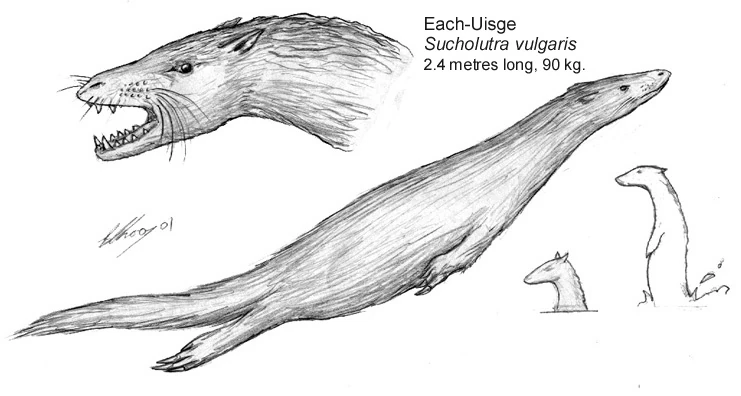

Each-Uisge (Sucholutra vulgaris)[]

The each-uisge ("ehk-whizkee") is found in cool lake environments in Great Britain and Scandinavia. Although beautifully streamlined for swimming, the each-uisge can travel considerable distances overland when looking for a new territory.

Voracious carnivores, each-uisges will take a wide range of fish, crustaceans, turtles and amphibians. They will opportunistically attack small dinosaurs by the waters' edge but their lack of a reptilian metabolism prevents them from mounting lengthy croc-style ambushes.

Each-uisges pair for life, the female gives birth to 3-5 semi-developed young which are nursed in a burrow or den to which the male brings food. Both partners retreat to the burrow to hibernate during winter.

The animal has unusual spy-hopping habits in the water, often pricking it's ears with its head and neck raised out of the water, giving it a horse-like appearance (leading to its common name). Occasionally, it will briefly raise the upper 2/3 of it's body out of the water vertically, giving a distinctly serpentine impression. This habit is almost certainly the source of unsubstantiated but persistent reports of a late-surviving elasmosaurid dwelling in Loch Ness.

Caspian Seawolf (Selkis chooi)[]

The head of a Caspian seawolf (Selkis chooi).

Unlike their relatives,caspian seawolves (Selkis chooi) are not at all social, and in fact individuals of this highly territorial species are fully capable of killing their co-specifics in battles over hunting grounds. The only time these predators tolerate each other is during and immediately after mating, when the male and female must first conceive, and then nurture the season's litter. Seawolf child-rearing follows the same general pattern of other suchotheriids, but in a dramatically shorter time, and on a much larger scale. Seawolves time their births to coincide with seaguin and jarrk nesting, and for a single month during which eggs and nestlings offer abundant food at little metabolic cost, the seawolf pups are stuffed with calories. They mature at one of the most rapid pace of any synapsid known. From birth to their first month, the pups literally grow from the size of a plantain to nearly 1.5 meters and 30-40 kilos.As food supplies diminish, the seawolves' old territorial instincts kick in and the parents drive off both each other and their pups. At this point, the pups, of which there are often over half a dozen, can more or less fend for themselves, and after the elements and a few violent intraspecific battles have winnowed the new generation down, the territorial lines have been redrawn, seawolf affairs return to normal.caspian seawolves are actually more widespread than their name sake indicates. Populations range along the European Atlantic coast into the Mediterranean and both the Black and Caspian sea. The size range can vary greatly. The originally described Baltic populations generally reach 300 kilos. The more southerly populations rarely exceed 200 kilos. These seawolves also are quite common in the reaches of very large rivers, such as the Danube and Dnieper. They are the fatal horror of unwary dinosaurs and mammals who wander down for a drink.

Rhoan Selkie (Selkis mysticum)[]

Rhoan Selkie, Selkis mysticum (Arctic Ocean )

Weighing up to 700 kg and often over 7 meters in length, the rhoan selkie is the largest metatherian on the planet. These predators travel in closely-knit packs through the waters of the Arctic, hunting their favorite food, seaguins . These large aquatic birds are formidable prey, and must be driven nearly to exhaustion by the pack before they can be safely killed and eaten. Selkies are easily capable of keeping up with a fleeing seaguin, propelling themselves through the water with undulations of the spine that must be similar

to the locomotion of our own time-line's early whales. Indeed, while the convergent each-uisges of Europe retain large and functional limbs, selkies, like those ancient whales, have begun to lose their hind legs, which are nearly functionless in their aquatic lives.

Rhoans breed toward the end of the long arctic winter, using their short gestation period to swim southward into either the Atlantic or Pacific depending on the population. The mated pair mark out an isolated backwater cove, even scratching out a den of sorts if needed. As soon as they have left the water, the females curl up to allow their tiny, marsupial pups to crawl out of their wombs. For roughly four weeks, these tiny babies feed upon high-calorie milk, while their father makes daily fishing trips in search of nourishment for their land bound mother. Once the pups are weaned, they are transferred to the father, who begins to teach them to swim and hunt while the mother fishes for the family. The rhoan parents may switch off as many as five times before the winds of winter rive them and their pups into the water, where they integrate themselves into a pack.

CROCOPHOCINAE (Selters)[]

Selters could be called be the 'little brothers' of their close relatives, the selkies. Smaller and more secretive, they are restricted in range and diversity due to competion with their relatives. Selters are known from about a dozen species found in Scandinavia, Africa, and the Americas, where they are most diverse. Diverging from the larger stagodonts in the late Eocene/early Oligocene, selters are less agressive and more playful in nature. Also, they differ in diet, selters prefering fish to red meat as a rule. More primitive than selkies, selkers' limbs are still developed enough for them to run on land (in short bursts).

Boreal "Gatordog"/Gotter (Crocophoca crocophoca)[]

The gatordog, a relatively small 4 to 12 kilo aquatic selter that has found the vast wetland expanses of Russia and North America beyond human ken. Yet in spite of their discomfort, many humans bypass the dry arctotitan steppes for the mosquito and fly bitten taiga. The taiga has secrets yet revealed, and Spec has been harsh in this area. Gotters prey on various fish and crustaceans, but thick cyprinoids are favored.

Even so, the gotter is a delightful aquatic predator to watch. They are quite curious, often coming up to boats and even clambering inside at times to sniff spexplorers. The first incident with a clan on the Lena river resulted in many startled folks dumping themselves in the drink. This resulted in the entire clan playfully nipping at fingers and toes. The second time, level heads waited calmly as the parents sniffed and licked the them before retreating in a bored manner back to their cubs.

Azorean Quout (Azorias quoallia)[]

The quout is a derived terrestrial selter that has reached the isolated Azores. Quouts prey on game fowl and nesting sea fowl, but also take various lizards and nestling turtles when available. Quouts also consume berries and nuts when in season. These 10 kilo critters mate during the spring, with both sexes sharing in the rearing of the young.

Amazonian Selter (Thylacolutra amazoniensis)[]

A typical species, the Amazonian Selter (Thylacolutra amazoniensis) is found throughout the Amazon River and most of it's tributaries. At up to 5 feet in length, the only predators they have are anacondas [if they or something like them exists in Spec] and large coelacanths.

Dobhar-choo (Thylacolutra maximus)[]

The largest selter is the Dobhar-choo (Thylacolutra maximus) of Scandinavia. At 8 feet long, it is the only selter that will normally eat large game, including small dinosaurs. Dobhar-choos have a distinct color pattern: mostly white, with black paws and a red 'dagger' on the back which is only present in males. These creatures live in pairs which share very deep bonds. When hunting, pairs will ambush most animals that come to drink, from dogbunnies to streks. If the the prey attempts to run away, a Dobhar-choo will run onto land if it's prey is close enough to the water and attempt to drag them into the water.

Water Panther (Selkis americium)[]

Water panthers can be found throughout the Mississippi drainage and across the great lakes of the boreal north as far as the Yukon. They also can be seen near shore along the eastern seaboard as far south as the Carolinas, preying on seaguins and duckotters. Water panthers are more primitive than their more ocean going cousins. They have fairly well developed legs, allowing them to lope like giant otters across great distances over land. These 250 kilo 3 meter long critters have been known to drive draks and errotyrants from their kills near the water's edge.

Clans may be very large, with a mated pair and several generations of their children all working together in a tight knit family. This is especially important for the Great Lakes bound members of the species, who often must share the onerous duty of keeping breathing holes open while hunting for the abundant shoaling fish.

Water panthers, along with seawolves, routinely kill inexperienced diving spexplorers. Both species regard wet suited humans as territorial competitors to be assessed. When around selkies, it is important to assume complete submission. This usually involves allowing a selky to grab a limb and drag you along for a short

distance; or a display gape which one should immediately insert your hand or camera into, substituting the head of a submissive selkie individual. Even the dangerous seawolves will quickly abandon their initial aggressive display for bored indifference.

PHOCASEIKINAE (Jarrks)[]

Jarrks are small selkies of many varied species. They have thick crushing molars and pointed premolars for a varied diet of clams, ammonites and pelagic fish. Average adult size in the clade is about 40 kilos, with the smallest species just 20 kilos and the largest topping out at 120 kilos. Jarrks are unusual among selkies in that they form gigantic rookeries right alongside or between seaguins. However, the resemblance to HE pinnipeds ends there, for jarrks form monogamous pairings just like their cousins.

Jarrks are more land bound than true selkies, they prefer to ride out storms in grottos and sheltered beaches. Jarrks, unlike selters and true selkies, have a moderate layering of body fat that gives them a plumper appearance, though nowhere near as rotund as HE seals. Jarrks and seaguins are often seen in mixed company, since both are heavily preyed on by selkies, sharks and empress seaguins.

Jarrk (Phocaselkis cacophonis)[]

The originally described species, jarrks can be found around the British isles to the Baltic sea as far south as the Bay of Biscay. Jarrks have given the clade their nomer due to the annoying "Jarrk! Jarrk!" calls they utter. A whole colony of hundreds of loudly calling animals can result in painful migraines for observers. Indeed, after several weeks, the watching spexplorers even started cheering whenever a jarrk died in the jaws of a predator.

This noisy conglomeration only lasts for roughly two months, by which point parents take their 2 to 4 pups out to sea. Life is dangerous for jarrks, they are frequently surprised by selkies or empress seaguins when they chase ammonites or forage for buried clams. Average lifespan for these 50 kilo selkies is about 7 years.

Whelker (Phocaselkis (Nassariophagus) labradoriensis)[]

This is the largest jarrk. The Whelker has a beautiful black and light tan coat intermittently spotted with white along their torso. These 120 kilo jarrks often prey on juvenile grass whelks *Phytonassariodes delawariensis*, named for the outward similarity of their shells to certain of their HE cousins. Grass whelks are voracious herbivores, consuming a great deal of vegetation. Whelkers will grab the snails, take them ashore and smash them open on rocks. Whelkers are a keystone species, by keeping grass whelk numbers down, large areas of loose sand and gravels are kept locked down. The vast plant beds are also important nurseries for host of other marine life forms.

Whelkers form colonies during the spring, often in estuaries on isolated sandbars. These colonies are often less than 50 mated pairs, with their offspring of previous years. Both the male and yearlings will provide their mother with fish and whelk meat while she nurses within a grass lined scrape just deep enough to keep her and the pups out of the worst of the elements. When the pups are three months old, she begins to hunt at sea with the older siblings keeping watch.

UNDESCRIBED SPECIES[]

Common otter selkie

Brown otter selkie

STAGODONTIDAE (Hoeks, Hombas and Baskervilles)[]

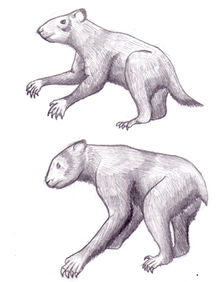

Distant cousins of the aquatic selkies, possum-hounds are a wide-spread group of Laurasian metatherians. These nocturnal carnivores may be found throughout the Northern Hemisphere, though their greatest diversity is in North America, where they take over many niches that, on other continents, are reserved for dinosaurs. Some, like the baskerville , approach the size of RL canids.

Many scholars link the possum-hounds to the stagodontids, a group of tasmanian-devil-like metatherians that produced such monsters as Didelphodon, the largest mammal known from the Mesozoic. Thus, the opossum-hounds' original name of Metacanidae has been discarded as a formal taxon, and Stagodontidae extended to include these modern species.

Baskerville, Metacanis phobos, common tirg, Seculasaurus vulgaris, and spotted jaub, Spadavis onca (north western North America)

Baskerville (Metacanis phobos)[]

The baskerville (Metacanis phobos) is the largest of the possum-hounds (Metacanidae), and can be found in the cold, boreal forests of Eurasia and North America (although the larger subspecies, M. p. gigas is endemic to North America). These carnivores range in size from 15kg (the Eurasian subspecies) to more than 20, and in most respects resemble the mustelid wolverines (Gulo gulo) of Home-Earth. Baskervilles are vicious and tenacious hunters, willing to run, climb, and swim in their pursuit of prey. They are also fond of carrion, which they locate with their excellent sense of smell.

The most noteworthy feature of the baskerville, a trait unique among mammals, is bioluminescence. For most of the year, baskervilles look like any other possum-hound, but during the mating season (January-March) the males develop a strip of green-glowing tissue along their spines. This skin is hidden by a mane of hair down the animal's back, and can be revealed by flexing sub-dermal muscles and spreading the mane apart.

The source of the eerie greenish glow that has earned the baskervilles their name is, in fact, the fungus Rhizolucifrus baskervillensis. This mushroom, a bioluminescent rhizomorph related to the genus Armillarielia (common to both Spec and Home-Earth), probably started out as a dermal parasite, growing as an infection on the skin of a possum-hound. However, the fungus's ability to glow (which it evolved for purposes of its own) must have proven useful to the ancestral baskervilles as a mating signal. A male that glows, after all, is a male that harbors a strength-sapping infection that reveals his location to predators and prey. The very fact that such a male is alive means he must have a set of very beneficial genes, and would thus make a good father.

Of course, the same infection that makes males more attractive has no beneficial attributes to females or juveniles, and so the baskervilles have evolved an immune response that inhibits the growth of the glowing mycelia. Most baskervilles do carry the fungus, but not in sufficient quantities to glow or to be of any noticeable detriment to their health. During the fall, however, the males' immunity begins to wear off. At the same time, they produce saccules of nutrient-rich fluid on the skin of their backs, which they rub against other males to spread the fungal spores. By early January, their backs are glowing brightly.

The glowing males' attractiveness to females comes at a price, however. Glowing males are noticeably less energetic than females and juveniles, their strength sapped by the fungus on their backs. They can, however, decrease the flow of nutrients to their phosphorescent saccules, damping their glow and saving energy. During hunting, a male baskerville can hide some of his glow by closing his mane over the naked skin of his back. Interestingly, breeding males often hunt together (a contrast to their solitary behavior the rest of the year), and seem to be able to use their glow to communicate over distance, opening and closing their mane like a semaphore to transmit a code of glowing pulses.

The European baskerville subspecies looks superficially quite different from its American cousins, but the difference is literally skin deep. The European baskervilles, nicknamed "tuonenhurtta" after the Finnish land of the dead, seem to be a partly melanistic variant of M. phobos. It is yet unknown what kind of advantage the darker pelt gives over the lighter colors, or if the darker fur is merely connected to another more clearly beneficial mutation.

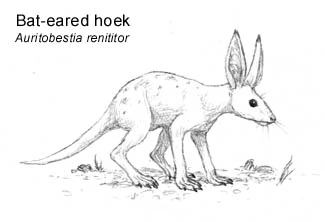

Bat-eared hoek (Auritobestia renititor)[]

The bat-eared hoek (Auritobestia renititor) is a fleet-footed stagodontid completely adapted to the arid environment of Spec's southwestern North America. This small nocturnal carnivore hunts for small lizards and snakes, burrowing beetles, spiders, scorpions and other invertebrates. The bat-eared hoek has a relatively good night vision, but this is nothing compared to its acute hearing. They can hear their prey moving beneath the sand from many meters away, and are claimed to be able to sense even the hearbeats of a still-lying animal.

Bat-eared hoeks are solitary animals, and when the paths of two hoeks cross, results may be rather violent. A cornered hoek can also defend itself very aggressively, and many a scientist has had the displeasure of proving the glove-pearcing sharpness of its teeth. When threatened, the hoek usually makes loud barking noises, which are said to resemble the sound of an asthmatic chihuahua. (The name "hoek" is in fact an onomatopoetic reference to the animal's bark.)

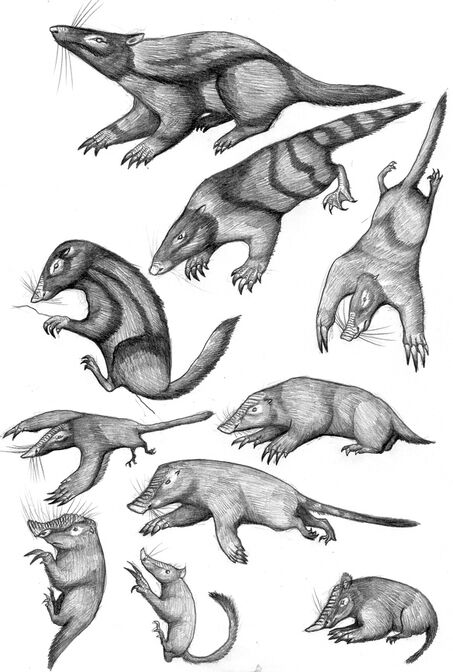

ENANTICYONINAE (Wepwawets and the Tectondogs)[]

This is a very unusual clade of metacanids. They share a fully digitigrade stance with hombas, as well as the loss of an upper pair of molars. However, they have traits entirely unique to them alone. They have more complex brains, especially with regards to areas reserved for socialization and problem solving. Their epipubis bones are reduced and very ossified. They provide structural support for several muscles and tendons but do not aid balance.

The clade is very young, less than 5 million years old. The wepwawets are an old off shoot that made it into the Saharan desert quite some time ago. 4 million year old fossils near the Nile river are little different from their modern day counterparts. The Tectonwolves are odder. They clearly are related to the wepwawets, but their earliest representatives are Mexican and Andean, some 3 million years ago. It seems they had a radiation from the Andes across South America and back north.

What makes the tectonwolves so odd is that both females and males can carry their young in pouch. Why this is so is not fully understood. Perhaps the first Andean tectonwolves utilize a novel mutation in a land that was new and dangerously unfamiliar. Whatever the case, tectonwolves form life long monogamous pairs that share the load in practically every way.

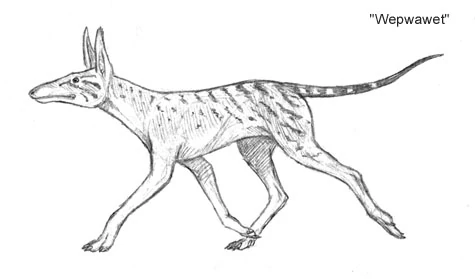

Wepwawet (Wepwawetis aegyptis)[]

In Spec, where terrestial predator niches are as a rule held by dinosaurians of different kinds, the North African wepwawet (Wepwawetis aegyptis) (named after an Egyptian jackal-headed god) is one of the few exceptions. Though this nocturnal predator greatly resembles the canids of Arel, it is in fact a stagodontid , and as such a brilliant example of convergent evolution. Not only does it resemble a large running dog, it acts also as a reminder of Arel's large marsupial predators, thylacines, while it is not closely related to the ancestors of either.

Even though wepwawet is geographically far removed from its closest relative, the hoek, the similarities are obvious. Both species rely greatly on their hearing to locate the prey, but also possess a good night vision. Both are also highly cursorial - wepwawet may indeed be the fastest mammal in Spec. Wepwawet is of course a good 10 kilograms more massive than its American cousin.

Black Dog (Wepwawetis diabolus)[]

A cryptic species found in the UK in heath, moorland, and woodland. Up to five feet long, it's the largest (non-paraselenodontian) mammal in Europe. An oppurtunistic predator, it takes meat of all kinds, carrion, spec-rodents, hog-bird and strek chicks, etc. As it's name suggests, it's completely black with yellow eyes. Despite it's intimidating appearance, it's actually quite a gentle and caring parent and mate, having liters of up to 4 pups.

Andean Tectonwolf (Enanticyon lycaon)[]

This is a very large metacanid, reaching nearly 40 kilos. They can be found in altiplanos as well as alpine deciduous and coniferous forests. Day time dens are temporary constructions in undergrowth or abandoned bastardsloth burrows. Nighttime is hunting time, with a wide range of prey being taken. Small mammals such as gondwanatheres and xenos along with small dinosaurs such as birds and bantams make up a good portion of their diet when single. Mated pairs frequently hunt much bigger prey, like spelks, nandrakes and un-gulates.

When the late winter mating season arrives, the pair mate frequently, even after the female is impregnated. Both sexes groom and travel together at all times. They maintain a bodily distance of no more than three feet at any one time, sleeping together for nearly a month. When the pups are finally born, both the mother and father carefully transfer a roughly equal number of the peanut sized offspring into their respective pouches. This time period is crucial for the pair and they may remain within a burrow for a week while both adjust to having nursing pups. Eventually, both parents leave the burrow to hunt. Their earlier urgency and passion has cooled much; enough that they will often separate for miles from each other. Generally though, they seek each other out at some random den every night. High hyena like whoops and whistles allow for each couple to come together without giving themselves away to potential predators.

The pups are raised for nearly six months in pouch. Afterwards, they are weaned off milk. The parents also start forcing the pups to follow them nightly outside of the pouch; often rotating tired pups throughout the night and early morning. Then by their 10th month, both parents permanently eject them. The pups will usually remain together for several more months within the general vicinity of their parents' territory before finally disbanding.

Tecthole (Enanticuon enanticuon)[]

This is the most derived of the tectons. Living in large complex family groups with up to 20 individuals. This hypercarnivore can be found in dense undergrowth in temperate and boreal montane forest and valleys in eastern Asia. They are found across most of forested North America. The small size of individual tectholes, at 8 to 15 kilos, not impressive, is more than made up for in numbers. These are big game hunters, pursuing streks, spelks and even taking smaller segnosaurs. Because they often course prey in dense forest that would hopelessly entangle errotyrant packs, they've carved a niche for themselves in utilizing secondary growth chock full of ensnaring brambles and young bushy trees. These places are ripe with streks and spelks retiring from draks and tyrants. A pack at full strength can bring down an animal weighting as much as 200 kilos.

The dominant pair breeds in late winter, with up to 15 pups born within weeks. The whole pack has eagerly awaited the arrival of the pups, and fawns over the pouch laden alpha female. After several hours or days of rest, the alpha female begins transferring pups into the waiting pouch of each member of the family. Each member selects a pup and stimulates it into releasing their mother's nipple. This strategy, having the burden of the young equalized throughout the pack, means hunting can be achieved much more easily. Every member of the family is present at kills to quickly consume it, reducing thievery and predation risks. With the pups safely within the pouches, permanent dens are unnecessary and the pack moves as needed. Their complex whistles and trilling calls allow for communication in the dense forests that are their homes .

ALOPECITHERINAE (Hombas)[]

Golden Homba (Alopecitherium gilvus)[]

Golden Homba, Alopecitherium gilvus (Holarctic Region)

The Golden homba (Alopecitherium gilvus) is the widest ranging of the stagodontids. Found throughout the Holarctic, these adaptable possum-hounds were the first to be collected. Their coloring and small size not withstanding; the remarkable convergence onto HE foxes led to the Richard Adams honorific for the group as a whole. Offspring are conceived in late winter, with 2-6 young crawling into the backward facing pouch. They remain there for three months, carried by their mother until weaning. During the latter part of the in pouch stage, the mother will forcefully expel her young to feed on caught prey and found fruiting patches. The weaning period results in permanent expulsion,with the young kits following their mothers for an additional month before both mother and father drive them out of the local territory. Golden hombas are quite flexible in food requirements as reflects their omnivorous nature. This coupled with their secretive natures has allowed them to spread from their North American homeland throughout the temperate and boreal forests of Eurasia. Golden hombas have even been seen far out on the Arctotitan Steppes, usually in close proximity to gallery and esker forests. However, they have not been successful in settling the temperate regions of North America.

Sylvan Homba (Alopecitherium urocyonoides)[]

The play at words here denotes both the more arboreal habits as well as the dusky silver coat of this homba. Found throughout the temperate forest regions of North America as far south as Central America, where they can even be found in tropical dry forests. This little metacanid is almost a kilo lighter than her wide ranging golden homba cousin. Nevertheless, conflicts between the two along the temperate-boreal borders always end up with the larger golden homba driven out or killed.

Golden hombas can supplement their winter diet with pine seeds, fungi and even lichens which grow on several of the conifer species of the taiga. Sylvan hombas find these unpalatable and toxic, which seems to explain their confinement to temperate zones where a greater variety of edible winter berries and insects can be had.

These hombas are important predators of many xenotheridians and chipmultis. The arboreal habits of sylvan hombas also constitute more than 40% of their diets. Many of the drays of arboreal multis and even pokemurid hollows are raided when one or both parents are absent. They are often taken by larger predators like draks and smaller tyrants. Reproductive cycles are much like their larger cousins, though daughters may stay with their mothers for a year before dispersing.

Tokala (Poavulpoides nebraskansis)[]

"Grass-fox" is a good name for this, the smallest homba. The Nebraskan prairies are not its only home, but the first specimens were collected from an overland expedition following the winding Platte River channels. This is the most basal homba; indeed, the Pliocene fossils in Texas have been tentatively referred to this genus. Uniquely among hombas, this animal rarely climbs trees, preferring to dart into tall grass and burrows to escape from predators. Strictly a grassland species, they range from Alberta south into Texas. Their diet is more carnivorous than the other hombas, mostly made up of the abundant small xenotheridians, multis and burrowing lizards present throughout the plains. Males also have a much greater role in parental care, often bringing prey to the litters he sires within his territory. Dog tokalas usually have one to three vixens within their home ranges. Weaned male kits may frequently den and hunt with their fathers during their first winter before he drives them out the following spring.

The absence of scansorial traits in tokalas may have to do with the lack of vulpessaurs in the great plains. Tokalas will also forage during early and late daylight hours, something the more derived hombas rarely do unless vulpessaurs are rare or absent.Tokalas do have the added benefit of numerous burrows they can quickly shelter in; indeed, tokala territories center around diggadum warrens, which are ubiquitous throughout all of the North American prairies.

Andean Homba (Alopecitherium chileansis)[]

This is the largest homba, with adults averaging 4 kilos. They are a relatively recent invasion into the South American mountain chain. Sylvan Hombas seem to be their closest relatives, splitting off within the last half million years. Except for their slate blue coat with rusty leggings and much larger size, they're quite similar. These hombas range from the mediterranean forests in the north all the way to the moist coastal rainforests in the south.

[]

TANUKINAE (Tanukis)[]

Tanuki (Spectanuki spectanuki)[]

The tanukis were an interesting Miocene and early Pliocene radiation of stagodontans found in Eurasia. They reached quite large size, with one Pliocene Siberian representative estimated to have been 1.5 meters long and weighting in at nearly 60 kilos. Today, they are represented by a single species restricted to the cold temperate regions of the northern Japanese and Sakhalin islands and the coast of Manchuria.

Tanukis are dedicated omnivores, feeding on just about any organic matter they come across that doesn't put up much of a fight. They lay down fat stores in winter and hibernate for up to seven months. Females are much larger than males, up to twice his size at 13 kilos.

DIDELPHIDAE (Opossums)[]

the Nekopossum, Pullididelphoides benseni (South America: Amazon Basin) is a small insectivore/carnivore metatherian.

Many New World marsupials belong to the large and varied family Didelphidae, which on Home-Earth is represented by opossums. These marsupials are distinguished by the fact that they give partial birth to an embryo from one womb into another, where it develops for a time before graduating to a pouch. Didelphids are very similar to the marsupial precursors, and most have retained the ancient habits of the arboreal insectivore.

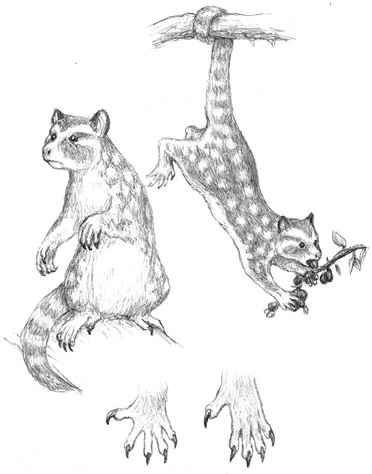

Sugar Cat (Shofixti reichefordi)[]

The sugar cat (Shofixti reichefordi) is a dweller of the rainforest canopy. Though it looks like a cross between a cat and a squirrel, it is a metatherian not unlike HE possums. The sugar cats were originally thought to be exclusive frugivores, but close observation has proven them to be opportunistic omnivores that will even occasionally raid arbronychosaur nests. Naturally these arboreal dinosaurs are also compete with the sugar cats for food, but the secret of the metatherians' success seems to be their prehensile tail that functions effectively as a fifth limb.

the antpossum

The sugar cats are monogamous and live in tightly knit pairs that rarely leave each others's sight. The males are known for their downright suicidal attacks against any threat against the litter they've sired. If a sugar cat feels its nest is being threatened, it may go completely berserk and fearlessly attack an invader as large as a human being. Since the sugar cats have large curved claws and cutting incisors they can do a lot of damage even if they perish in their desperate act of defense.

POLYDOLOPOIDIDAE (Stimpies and teddies)[]

THYLACOURSINAE (SAMPLE TAXA: South America) []

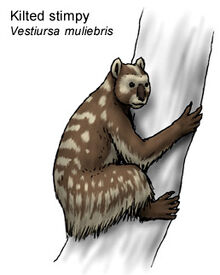

Bluenose stimpy, Thylacoursoides kricfalusii (South America)

Thylacoursines, called variously "teddies", "spec-bears", and "non-koalas", are placid, heavily-built didelphids that evolved in North America during the Miocene and invaded South America during the Great Interchange of the Pliocene. Most thylacoursines are omnivorous or herbivorous, but one genus Thylacoursus is actively predatory. The "drop-bear", if it exists, is probably a member of this genus.

Stimpies and teddies are placid, heavily-built arboreal metatherians somewhat related to the didelphids. They evolved in South America, and the vegetarian, koala-like stimpies are found only in that continent's jungles, but the more omnivorous teddies extend far into North America.

Though deceitfully similar to koalas in appearance, stimpies (genera Thylacoursoides and Vestiursa) are only distantly related to the Australian marsupials. The large hairless noses of stimpies are used by the marsupials to tell different species from each other as well as sexual ornaments and resonance chambers to amplify the stimpies' calls. The existence of such an organ has lead many biologists to question the old view of stimpies as solitary animals.

The smaller, somewhat more nimble teddies (genus Thylacoursus) extend throughout South America and most of North America , although they vary little with distance. Most are small, no larger than 2 kg, but there have been several reliable reports of a much larger Thylacoursus species in the deciduous forests of western North America

Kilted Stimpy (Vestiursa muliebris)[]

The kilted stimpy is the smallest stimpy species known, weighing only 5 kg. They are also the only stimpies known to jump between trees ---other stimpies prefer to climb down if they cant travel between trees by walking from branch to branch. This may also explain the peculiar hairy "skirt" or "kilt" after which this stimpy has been named. The elongated hairs on their arms and rear legs may help the kilted stimpies to extend their jumps further, as in the stiff plumage of a pithecosaur.

Spectacled Stimpy (Marsupiursus hilaris)[]

Spectacled stimpies (Marsupiursus hilaris) are fairly silent creatures for most of their life, but during the mating season they make an exception. The female in heat calls for males with a low howl: "Haah-peeh, haah- peeh, haah-peeh". Any nearby males answer to the female's call with a high-pitched "Djyo-ee, djyo-ee". The few that have had the opportunity to witness this have described the experience as "nothing short of surreal."

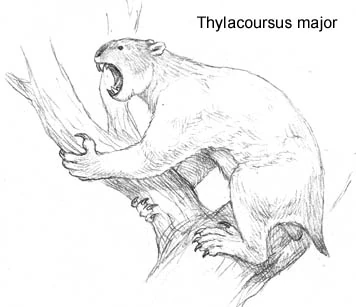

Drop Bear (Thylacoursus major)[]

The drop-bear is one of Spec's numerous cryptids. It has never been scientifically described although most non-scientists classify it as Thylacoursus major. Apart from a few somewhat confused and occasionally contradicting records by alleged eyewitnesses, there is no evidence for its existence. But considering how young a field of science the biology of Spec is, this is by far no sufficient reason to declare it fictitious. Thus, in the interest of completeness (or perhaps neurotic pedantery), we feel it should be mentioned among its possible relatives.

Several reports exist of a large, arboreal, carnivorous mammal that lives in the subtropical forests of southeastern North America. Over a metre in length, it is said to lurk in the trees and let itself drop (hence the name "drop-bear") on unsuspecting prey like young singers or butterfly-collecting spexplorers, attempting to kill it with fearsome claws and dreadful teeth.

An impressive amount of cryptozoological literature exists on the drop-bear. Most of those who believe in its existence think it is a teddy or even a stimpy. Such a carnivorous member of these groups may seem a hilarious thought, but it wouldn't be weirder than the biggest mammalian predators of Home-Earth's Australia, the marsupial lions (Thylacoleonidae), which have been called "killer koalas"; lacking canines like teddies and stimpies, they used their large thumb claws and their once-gnawing incisors to stab prey (like how other carnivorous mammals use their canines), and their large, bladelike premolars to cut it to pieces.

But even if so, what is this animal doing so far from home, be that South or Central America? Some have speculated that the drop-bears may have evolved on the Caribbean islands – even though, so far, no such animals have been reported there, but then the islands are all severely underresearched – in the absence of predators of comparable size, and that they then somehow crossed over to Florida. Crossing the Florida Strait in spite of the Gulf Stream would be quite a remarkable feat. Others assume that the ancestors of the drop-bear migrated north along the normal route through Central America, but so early that a continuous warm forest existed throughout the length of the route. Others again wonder if temperature is really so crucial; they point to a sighting of some large moving dark clump that was seen on a tree in the central Appalachians, though after sunset and at a distance.

Blackback Teddy (Epidolopoides ater)[]

The blackback teddy (Epidolopoides ater) is one of the more omnivorous members of the group. Consequently, its lower premolars are distinctively dagger-shaped . Insects and other small animals make up about half of its diet, while the rest consists of fruits, seeds, buds and some young leaves. Large troupes of these small animals can be seen and heard chattering in the morning and evening in the rainforest of Central America.

Redback Teddy (Epidolopoides rubrodorsum)[]

A close relative, the redback teddy (Epidolopoides rubrodorsum), can be found anywhere one looks in the northern Amazon and Orinoco basins. Other species of Epidolopoides range south and west to the Atlantic rainforest; two geneticists are currently trying to find out how many species there really are in this complex.

Painted Teddy (Thylacopithecus pictus)[]

The painted teddy (Thylacopithecus pictus) is among the middle-sized teddy species, measuring some 50 cm in total length (without the long pinkish hairs on the tail). It is the most colourful known mammal of South America, if not the world, sporting bright blue eyes, a shining white patch of fur on its chest, yellow-orange blots in the face, on the inside of the hindlegs, on the back and on the throat, a dark brown to black "beard" along the contours of the lower jaw, but also on the edges of the large, round ears, and pink-looking mixtures of red and white hairs elsewhere. Presumably this is connected to the fact that marsupials aren't as colour-blind as placentals. Interestingly, both sexes look identical.

Painted teddies are fast climbers, frequently brachiating with their long forelimbs to move along branches too thin to reasonably walk upon. They are often seen hanging from a branch by one arm and using the other to pluck fruits from the same branch. Apart from eating leaves, buds and seeds, and just about any large insect that crosses their path, painted teddies are said to have a special taste for blossoms.

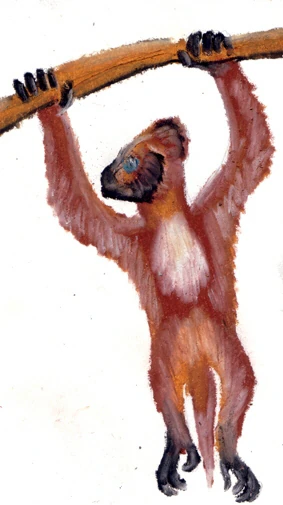

Choo's teddy (Thylacanthropus chewie)[]

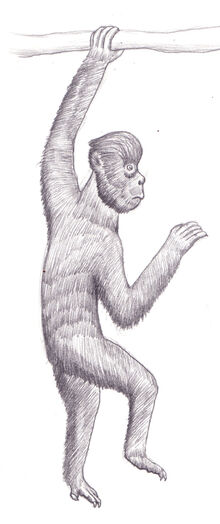

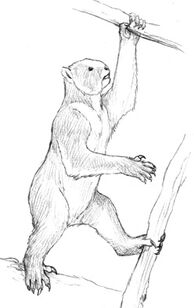

Choo's teddy (Thylacanthropus chewie) is a remarkable animal. It lives in the cloud forest of the eastern rim of the Amazon basin, making it difficult to study and giving it a fame of mystery. It has been called "the closest thing to an ape that exists in Spec", "Spec's caricature of mankind", and several newspaper headlines even read "Marsupial Man" – which is what its scientific name means. More sarcastic biologists, however, say that the most human-like characteristics of Choo's teddy are its lack of a tail and its large size; the males regularly reach a metre in length.

Choo's teddies move mainly by brachiation. This means they are used and partially adapted to a vertical body posture; indeed, when the teddies walk on thick tree limbs, they use only their long hindlegs, holding the even longer forelimbs high above the head, like the gibbons of Home-Earth. They never come to the ground, not even to defecate; they simply let their droppings drop. Expeditions to the otherwise idyllic cl

oud forest have started wearing stable helmets that can withstand the impact of sausage-sized faeces from a height of 20, 30 or sometimes more metres.

A large part of the diet of Choo's teddies consists of fruit. Choo's teddies migrate over astonishing distances to find fruit-bearing trees; brachiating is an energy-efficient way of locomotion. Large seeds and nuts seem to make up the second largest part of the diet; the extremely short, high head, along with the large, broad molars and the rather short lower premolar, is often interpreted as an adaptation to nutcracking. But leaves and buds are likewise on the menu, as is the occasional insect. Reports of Choo's teddies plundering nests are unconfirmed.

Normally, Choo's teddies are rather solitary, even aggressive animals. In the mating season (December and January), however, males and females call each other using a feature that is probably unique among mammals. The call has been described as an "asthmatic gurgle", but it can become surprisingly loud because of the resonance chambers, the greatly enlarged frontal sinuses that form the top of the skull roof and give the deceiving appearance of a human-size brain. Males have deeper voices because they are larger.

Spexplorers have recently succeeded in filming the birth of a Choo's teddy. The mother, sitting on a thick tree limb and leaning backwards against the tree trunk, uses a finger to comb the thick, felty fur (which is, interestingly, the same colour as the faeces) out of the way from the vulva to the entrance of the pouch. The newborn passes this distance – still no less than 20 times its own length – astonishingly fast. It sticks its head out of the pouch for the first time some six months later.

Blacktail Teddy (Polydolopoides melanura)[]

Blacktail teddy, Polydolopoides melanura (Atlantic rainforest of South America) and Striped teddy, Arctocephale arcuata (south of the Amazon)

Only living in South America's Atlantic rainforest, the blacktail teddy (Polydolopoides melanura) is one of the teddy species with the smallest distribution. But it is easily the best-researched one.

Blacktail teddies eat just about anything they can get, as long as it's digestible. This ranges from young leaves, fruit and seeds (the bulk of their diet) to insects and even not too poisonous frogs which they catch with their forepaws. Blacktail teddies also regularly plunder the nests of birds and arbros, and occasionally gnaw a hole in tree bark to lick the sap. The teddies themselves are hunted by the larger species of skreechers and flankers.

Striped Teddy (Arctocephale australis)[]

Another species is the striped teddy (Arctocephale australis), can in principle be found (if one is lucky) almost anywhere south of the Amazon. Its scientific name alludes to the arc-shaped stripes that begin behind the teddy's eyes and seem to fall over its back in several waves.

Great Teddy (Arctocephale crassa)[]

The great teddy (Arctocephale crassa) is the second-largest described teddy species. It measures some 90 cm in total length, resembling the larger stimpies in size [can someone perhaps suggest a reasonable weight?], though not quite in apathy. Generally similar to the white-faced teddy, it differs mainly in its diet, which includes more leaves and more nuts from the upper stories of the rainforest. It often comes to the mangrove forests along the north and east coasts of South America to feast on the fat-rich seeds that are hidden in the large, spiky cones of the [name] manglar tree.

White-Faced Teddy (Arctocepale bicolor)[]

A typical representative of the Marsupiursida is the white-faced teddy (Arctocepale bicolor). It lives in the highest story of the rainforest throughout the Amazon basin where it eats mostly fruits, nuts and young shoots.

Plush Teddy (Phascolarctothrix roosevelti)[]

The plush teddy (Phascolarctothrix roosevelti), named after its soft fur, is a nimbler animal. Some 60 cm in length and perhaps half a great teddy in weight, it climbs fast and steadily in search of fruit, nuts, buds, but also the occasional bird nest. For these reasons, among others, biologists put it close to the Thylacopithecidae.

Plush teddies can be found in the middle stories of the rainforest of the upper Amazon basin, occasionally above an altitude of 2,000 m.

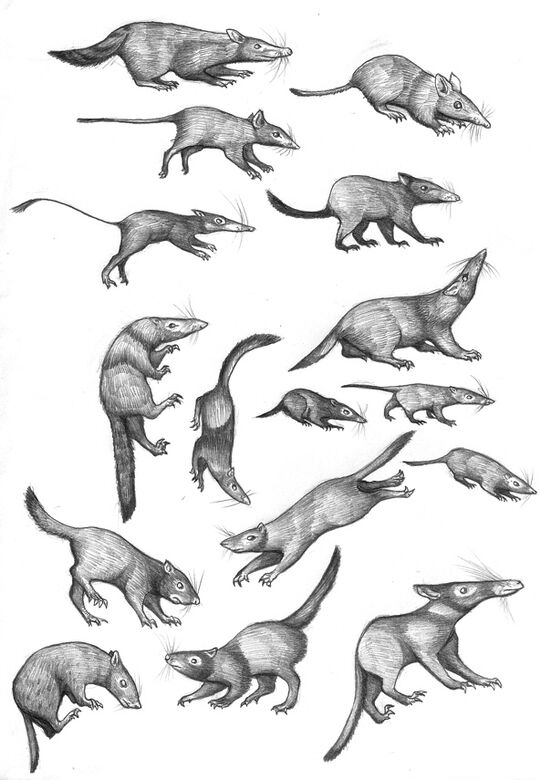

PUSILLONECATORIDAE[]

All pusillonecatorids mentioned here in descending order.

Widespread throughout Spec, the pusillonecatorids fill the niche that is otherwise occupied by the mustelids on HE. They are quite common and successful small predators, and are often themselves prey for larger carnivores.

Notabrock (Parametameles apates)[]

The notabrock (Parametameles apates) is a pusillonecatorid trying very hard to be a brock. Unlike its Holarctic relations, the notabrock can be found in Africa, and is more closely related to the weasel-like pusillonecatorids than the badger-like seismonychids. At any rate, its habits and behavior are sufficiently badger-like: it is an indiscriminate omnivore, and also has a sweet tooth that attracts it to bacchus-tree fruit drops.

Short-Tailed Vair (Metamustela nivalis)[]

The short-tailed vair (Metamustela nivalis) and its relatives are the closest on Spec to weasels. Aggressive and deadly little hunters, they will prey on animals substantially larger than themselves by going for the throat and clinging on till death ensues. Despite their ferocity, they commonly fall prey to avisaurs, kronks, scowls, pokemures, and even their own kind.

Laccolithon (Geodeltatherium grecoi)[]

North America's Great Plains is home to large groups of Laccolithons (Geodeltatherium grecoi) . Living socially in groups, these pusillonecatorids move into uplift glyphon burrows and take them for their own purposes. Despite the presence of the large lizards, neither of the two species seems to ever enter into conflict, with only the occasional squeak betraying the collision of an industrious glyphon into a resting laccolithon. While the glyphons expand the burrows, the laccolithons, with their sharp eyes, keep a watch for predatory animals by sitting upright. As the lizards feed on insects and the deltas forage for vertebrate prey, competition is duly avoided.

Montezuma (Montezumustela striata)[]

The Montezuma (Montezumustela striata) can be found throughout South America as a generalist arboreal hunter. Fast and agile, montezumas use their quick reflexes to dash at top speed between tangles of otherwise inextricable branches. They will prey on lizards (including the ponderous treeguanas), snakes, birds, and mammals, and regularly raid treetop nests. Montezumas are quite fearless and will follow prey to the tips of the flimsiest twigs, relying on a catlike aptitude to survive falls. They are one of the very rare few possum weasels to have invaded the realm of the death multis.

Williamson's Tarka (Tarka williamsoni)[]

Williamson's tarka (Tarka williamsoni) is the best known of a group of pusillonecatorids that approximate otters. Found from the British Isles to the Mediterranean, Williamson's tarka is a highly adaptable amphibious animal that will eat almost anything, is an agile swimmer and a quick sprinter, and is as much at home up a tree as it is in a river or the sea. Tarkas have been observed diving to great depths to snatch shellfish and garbargee eels. The whistle of a tarka ("Ic- yang!") is very distinctive, and is often heard before the animal is actually seen.

Northern Fitch (Pseuderminea mustela)[]

The Northern Fitch (Pseuderminea mustela) and other fitches are the stoats to the vairs' weasels. Fitches are larger than vairs and feed on even larger prey with the same throat-bite, but lack the hair- trigger temper and irascible attitude of their smaller relatives. Fitches are relentless trenchermen, and spexplorers have often appreciated their propensity for eradicating xenos, even the repulsive naked sweat mice. It is likely that they would make excellent pets and companion animals for humans, but no-one has bothered to try domestication yet.

Waistcoat Deltamandua (Bicoloripelta africana)[]

The waistcoat deltamandua (Bicoloripelta africana) can be found in African savannah and scrub. A ground-living generalist, it has a fondness for insects, especially social insects. Termite mounds, anthills, and bee's nests are favorite haunts, and it guzzles the insects down with glee. A thick pelt with unusual, "waistcoat" markings provides ample protection from bites and stings. Deltamanduas have strong digging claws on their hind legs which they use to break into nests, and to defend themselves by kicking backwards.

Channel Snoat (Pusillonecator myxinis)[]

Natives to Europe's coastline, the channel snoats (Pusillonecator myxinis) are scavengers and beachcombers, nimble little opportunists that feed on the smorgasbord of food to be found on Spec's bountiful shore. A small, lithe body allows snoats to skitter between rocks and ferret out food, which includes mollusks extracted daintily from their shells, fish gaffed neatly from the water, and seabird eggs taken in pairs one snoat distracts the parent while the other gluts itself. Snoats are also invaluable scavengers, crawling into a dead animal to devour it from the inside out. Other species of snoat can be found on riverbanks, in forests, and on the high alpine peaks.

Pastinaca (Obnoxiotherium pastinaca)[]

The pastinaca (Obnoxiotherium pastinaca) is a large, omnivorous Asian jungle beast. Its brightly colored and striped pelt, and foul stench, fully advertises its nasty defense to predators. If attacked, a pastinaca arches its hindquarters over its back in a spectacular feat of contortionism, and fires at its attacker's eyes with a noxious fluid ejected from glands in the anus. Whether this fluid is manufactured by the pastinaca, or is synthesized from the toxic plants that the pastinaca feeds upon, is still a matter of conjecture. The pastinaca itself has no problem guzzling virulent fruit, not to mention a wide range of small prey.

Other pusillonecatorids include the wabasso (Metamartes), A strictly American radiation with several species. Some poorly known African rainforest species are still being evaluated as of this writing. There are also three recently collected specimens from the Eurasian taiga that may represent new species or even genera.

SEISMONYCHIDAE[]

All seismonychids mentioned here in clockwise order.

The seismonychids, or Spec-badgers, are deltatheres clearly distinguished from their pusillonecatorid relatives. While the pusillonecatorids are small weasel-analogues, the seismonychids have expanded into the burrowing and digging niches. Seismonychids are widespread over the globe in various badger, mole, and desman roles.

Bloody Bill Brock (Metameles sanguineus)[]

The bloody bill brock (Metameles sanguineus) is the largest and most distinctive member of the family. Males may occasionally reach 30 kilos. A European species, this massively built omnivore will eat everything it can get at. Pretty much anything that moves is fair game, but there is no shame in munching on berries. Bloody bill brocks are tough fighters and relentless diggers, and have few enemies in the wild. The related timmy and tommy brocks are smaller and less aggressive.

Shatterlogs comprise a compact genus of semi-amphibious brocks. Distinguished by naked and webbed hind feet, shatterlogs dig burrows on riverbanks, and use them as a base from which to hunt frogs, fish, and other small animals. The burrows are quite complex, and can never be totally flooded. A parent shatterlog will dart out of its burrow at startling speed if it feels its offspring to be menaced. These relentless predators often use gnawed and broken branches to mark territory, hence the name. Pictured here is an American bank shatter log (Fluviomeles jacquesi).

The largest subdivision of the Seismonychidae is the Plissorhyninae, known as schnozzles. These animals have a unique and unmistakable nose: bare-skinned up to the forehead, large, drooping, and heavily wrinkled. The wrinkles increase surface area massively both inside and out: externally, they provide more tactile surface, while internally they allow more space for sensitive chemoreceptors. The snout is highly flexible and exploratory, and a full complement of whiskers rounds out the sensory array. Plissorhines may have the most powerful olfactory and tactile senses in Class Mammalia. At any rate, the nose must be the key to their success members of this family outnumber other seismonychids three to one in both number of species and diversity.

Girdled Schnozzle (Rhinotalpa hemicincla)[]

The girdled schnozzle (Rhinotalpa hemicincla), shows usual plissorhine adaptations: powerful digging legs, weak back legs, and the diagnostic wrinkled snout. In this species, the snout-pad does not reach up to the forehead. While this was previously seen as a primitive trait, it is now being reconsidered as a schnozzle moving up and out. Girdled schnozzles are water-loving and less subterranean than the rest of their group.

Silver Schnozzle (Plissorhinus argyrus)[]

The silver schnozzle (Plissorhinus argyrus) is a typical schnozzle. Filling in the mole niche in temperate to cold areas (glyphons are dominant in warmer climes), the silver schnozzle digs extensive tunnel networks to seek out small invertebrates and the occasional lizard. Its fur gleams silvery in light, which is hardly ever seen as it spends almost all its time underground.

Florida Schnozzle (Riparitalpa floridiana)[]

Florida schnozzles (Riparitalpa floridiana), as their name implies, may be found in Florida, but then they are widespread in various marshy environments. Larger and more powerful than most schnozzles, these hardy beasts build and shore up riverside holes from which they continue excavating. They are good swimmers and have been known to feed on fish.

Pack-Noses (Pachynasotherium troglodytes)[]

Pack-noses (Pachynasotherium troglodytes) are primarily desert dwellers. Living in holes excavated in rock crevices, these tough schnozzles come out at night to feed on insects and to gather grass and leaves to line their nests. They are tasty snacks for countless other desert animals mattiraptors, avisaurs, vipers, small draks, kronks, larger metatheres .

Edible Schnozzle (Nasotupaia glis)[]

The edible schnozzle (Nasotupaia glis) was unfortunately named after an early spexploring expedition, on the verge of starvation, survived by feeding on these abundant little creatures. These creatures stand out from the rest of their family as tree-climbing, agile schnozzles. Like the rest of their family, they come out only at night, and use their nose to ferret out prey.

Crevice-Runners (Lithotalpa hirsuta)[]

Crevice-runners (Lithotalpa hirsuta) are found in the karst habitats of Eurasia, acting much like rock hyraxes. Again, they are indefatigable burrowers, tunneling during the day and emerging by night. The bristles and whiskers on the face are particularly well developed, to aid it in making its way through a treacherous maze of sharp rocks and gaping holes.

Winged Moles (Pterotalpa musculus)[]

Winged moles (Pterotalpa musculus) were once considered cryptid jokes, but recent discoveries have proved their existence. These schnozzles have enormous arms (almost wings) that practically dwarf the rest of their body, and as such are powerful burrowers. The hind legs are just about vestigial, and winged moles rely solely on their arms to pull them through the earth.

Masked Ranger-Mole (Personatalpa kemosabei)[]

The masked ranger-mole (Personatalpa kemosabei) is a non-plissorhine trying very hard to be one. The snout is bare at the tip and slightly wrinkled, and it functions in much the same way, but any resemblance between this brock and the schnozzles is purely convergent. In addition, ranger-moles are much more active, and may cover large distances by night in search of prey. By day, they sleep in excavated burrows. This species is native to the American Southwest. It may be identified by its odd chuckling growl, transliterated by imaginative spexplorers as "tu-de-dum, tu-de- m, tu-de-dum-dum-dum ".

Grumbler (Thylodachius saskatchwannensis)[]

Another well known seismonychid is the Grumbler (Thylodachius saskatchwannensis). They are quite powerful critters, these 12 kilo diggers are mostly diurnal hunters of the prairies and dense eastern forests. Multis and glyphons live in mortal fear of these determined burrowers. The savage disposition of these critters is well known. Grumblers have incredibly thick yet flexible hides with stiff fur that allows them to turn completely around a tight corner underground.

ESURIMALAIDAE[]

All esurimalaids mentioned here in descending order.

The zams resemble the shrews of HE, they both are tiny fast living insectivores with fantastic metabolic rates. There is little difference between the two in lifestyle. However, there are some significant morphological differences. The zams appeared to have descended from a rat size generalist omnivore, Vulgarihaina closely related to the pediomyids of late K North America. The early Eocene shows a radical departure from that Paleocene generalist. Ironically enough, the widespread extinction of most pediomyids allowed the early esurimalaidids to fill in their niche as small specialized insectivores.

Esurimalaidids are highly convergent on HE shrews in many respects, they are incredibly small, with many skeletal simplifications and even lack of ossification is some respects. Their molarforme teeth are zalambdidont. Zams use thick shearing canines, not incisors to seize insect prey and the enamel is always white; but otherwise, the dentition is remarkably similar.

There is one very important difference. Zams do not use echolocation like HE shrews. Indeed, zam eyes are quite large and well developed. The visual centers of their brains are extraordinarily complex. However, zams also possess a very good tactile response through their vibrissae, much like HE cats. Zams will often extend their whistles over prey to determine what sort of food it is. Zam hearing is quite decent and their sense of smell is very good, though in blind tests compared to HE shrews, they lag considerably. As for venomous bites, there is no indication that any zam has venom or poison in any delivery method what so ever.

Zams are found on every continent but Australia and Antarctica. They have yet to really penetrate South America past the Andes. Zam species diversity is believed to be somewhat lower than HE shrews. This is due to observations of ground foraging Spec "bats" and birds that often utilize resources that HE shrews monopolize.

Zams mate from early spring into late fall, often having up to 8 litters a year. The young are born anywhere from 3 to 8 days after impregnation. Zams have pouches, but they are raised ridges running parallel to each other over the stomach. The mother's twin pouches are sufficient to hold the young securely for two weeks before she deposits them in safe burrows for short feeding forays. The young are soon following her around and disperse within the month.

Taiga Snucker ( Arctosoricoides abies)[]

The taiga snucker ( Arctosoricoides abies) sniffs its way through the pine needles and duff of the boreal floor. Taiga snuckers often store away large quantities of meat and fruit in deep holes near the permafrost line. This allows them to survive during those lean winter days when live food is hard to come by.

Cave Zam (Spaeluncimys sylvis)[]

The central European alps have many different zam species. One of which is the cave zam ( Spaeluncimys sylvis ). Cave zams actually are more common outside of earthen grottos in forest loam. However, if a cave frequently gets insects blown into it, many zams may set up shop for many months.

Quagmire Dancers (Saltatorisorex paludis)[]

Quagmire dancers (Saltatorisorex paludis) are small denizens of the huge lowland peat bogs found around the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. These little zams seek out springtails, beetles and other insects by scurrying and leaping across the mosses. When predators threaten, they do a spectacular leap of nearly a third of a meter into the bogs, burrowing in rapidly from sight.

Oak Snucker (Arctosoricoides quercus)[]

Oak snuckers (Arctosoricoides quercus)are common in temperate forests along the lowlands east of the Appalachian mountains in North America. They are voracious little critters, taking vertebrate prey several times their own weight when desperately ravenous. One oak snucker was seen dragging a chipmulti several dozen feet to a secluded hole.

Birch Dancer (Saltatorisorex betula)[]

Birch dancers (Saltatorisorex betula) are frequently seen in birch stands rooting out beetles and meal worms. The zams are important at keeping these insects from devouring birch roots. Males do a courtship dance where they flips backwards over the females.

Log Zam (Allosorex incolalignum)[]

Log zams (Allosorex incolalignum) are found throughout the temperate rainforests of North America's southern Appalachians. Much grub can be found in fallen log hollows and log zams specialize in listening and sniffing out beetle larvae gnawing through the wood. Once a grub gives it self away, the zam will rip open the rotted wood and grab the writhing maggot. The sharp teeth make quick work of them.

Closely related to the log zam are the two species of creeper zams Arbrosorex ferox and Arbrosorex dryas . Both species normally are terrestrial foragers in the warm southern bottomlands of North America. They will climb shrubs and fair sized trees to reach fruits and glean caterpillars off of twigs and leaves.

The three species of Parvaesurimalaid are the cyprus zam, Parvaesurimalaid cyprinus , the smallest of the zams so far, rivaling the smallest HE shrews. P. levantius , the levant or Lebanese zam and P. triesta , a zam found along the northern Aegean sea coast into the Bosporus straits.

The four species within Contunderamalas or crushjaws are odd african rainforest specialists on tortoise shelled beetles, terrestrial mote crabs and other thick shelled arthropods. The crab crushjaw (Contunderamalas cancrivora) lives along small streams where it dives for small crustaceans. The Cameroon zam ,( C. camerooniensis) is a more typical forager of leaf litter though it follows the waste trails of spiny tortoiseshell beetles, very difficult insects to crack open. C. zairiensis , or Zaire zams, are crushjaws redeveloping a more slender skull for typical zam prey like caterpillars, grubs, worms, and thin shelled insects. The mouse crusher, C. carnis will frequently kill xenos and lizards twice it's own weight.

Probe Zam ( Hypernaris gigas)[]

Probe zams ( Hypernaris gigas) are the largest zams, reaching some 8 inches and roughly 150 grams. They are found in shattered rock falls in the northern Mahgreb region of Africa. Probe zams stick their long snouts in crevices constantly throughout the cool evening hours. Minute insects are simply lapped up with a long sticky tongue. Larger prey are dug out and crushed up with the teeth.