INTRODUCTION[]

Multituberculates are an ancient form of crown-group mammals that evolved in the Middle Jurassic (but with a possible Late Triassic record) and spread across the world in a number of ground-dwelling and arboreal forms, as "the rodents of the Mesozoic".

HISTORY[]

Multituberculates probably evolved in the Bathonian of the Jurassic period (or even earlier) and spread across the world in a number of ground-dwelling and tree-dwelling forms, as "the rodents of the Mesozoic". Multituberculates are named for their molars, which have lots of cusps arranged in parallel tracks. Multies grind their food by moving the lower jaw back and forth with a truly bizarre group of facial muscles. They also do not gnaw with incisors in the upper jaw, as do rodents, but with a pair in the mandible.

Multituberculates must be regarded as one of the most successful mammalian clades that ever lived. Multituberculates in HE survived the K/T extinction event and had their heyday during the Paleocene. The rise of the Glires seems to have had a direct impact on their numbers though; they rapidly declined until the Oligocene, when thelast fossils are known.

Spec is of course somewhat different. The K/T event neveroccurred and multituberculates have continued into the present. Their ecological track parallels and even exceeds HE to an extent. Most of the 40 million years of the Paleogene seems to have been the ultimate heyday of the clade. Numerous diverse forms arose duringthis time from many different families; arboreal, terrestrial, fossorial, and even aquatic. The multituberculates seemed to have only continued their reign with little in the way of competition; some estimates state a peak of nearly 2,000 species may have existed in geochronological sympatricity in the late Eocene. There were few other rodentimorphic mammals during this time period. The arboreal primate plesiadapiformes were the most prominent example; with a few scrapes hintingat some very marginalized eutherian and metatherian also-rans. There appeared to be nothing to stop them from retaining their crown through the Cenozoic and beyond.

Until the arrival of the Neogene grasslands. The Oligocene/Miocene turnover was very dramatic. Vast savannas and steppes suddenly replaced earlier mixed herbaceous shrubbery as well as expanding into previously desertified regions. Seasons became much more pronounced, not just because of climate change alone, but because the new vegetational makeup of vast areas of the planet responded very differently to those alterations. The arrival of this entirely new ecotype allowed many unknown or very marginalized clades within Theria; among them, the xenotheridians, the un-gulates and the bilmys, to explode across their respective continents. These rodentimorphic critters were far superior as cursorial inhabitants of open landscapes than any multi.

Therian mammals also seem to have independently evolved hypsodonty quite easily multiple times, while multis have only developed it twice among the gondwanatherans and the Taeniolabididae. This, in combination with the cursorial adaptations of many therian clades, may explain why the multis have reduced in diversity throughout much ofSpec.

For the multituberculates, this was a disaster. They lost much ground and retreated to arboreal, fossorial, aquatic and atypical carnivorous niches. Only the island continent of Madagascar preserves a true diversity of typical multituberculate forms. The multituberculates are still losing ground; the Pleistocene saw many extinctions. The cimolodontans were reduced to just four clades, the squirrel-like Neoptilodontidae, the burrowing Taeniolabididae and Djadochtatheridae; with the carnivorous Necobataaridae finishing the list.

The other great multi "clade", the paraphyletic "plagiaulacidans" have as their single Spec crown-group, the gondwanatherans. Ironically enough, the gondwanatherans lack any plagiaulacoid premolars so prevalent among cimolodontans. Instead, they all possess hypsodont teeth suitable for shearing and grinding extremely noxious and fibrous plant matter unpalatable to most other animals except for glires and certain ornithischian dinosaurs. Within the gondwies are the Ovomeridigopheridae, the relictual Sinocastoridae, the two members of Aotearoaedae and the diverse Enantinesomyidae of Madagascar. Extant multituberculates today number an estimated 700 species.

BIOLOGY[]

Although they are often classified as a broad group of mammals along with either the monotremes (egg-laying mammals) and therians (marsupials and placentals), multies possess a unique anatomy that places them somewhere between the two. Multituberculates are named for their teeth, which do not form grinding molars as in other mammals, but instead grow in parallel tracks, like the teeth of a comb. Multies do not grind their food with these teeth, but shear it back and forth with a truly bizarre group of facial muscles. They also do not gnaw with incisors in the upper jaw, as do rodents, but with a pair of teeth in the lower jaw. They are warm-blooded, fur-covered, and give birth to live young, but, like monotremes, multituberculates lack nipples and dribble milk from patches of modified skin. Arboreal neoptilodonts are also known regurgitate food into the mouths of their tiny offspring in the same manner as birds.

The multis retain a lot of basal characteristics. They have a sprawling gait due to their primitively complex shoulder and pelvic girdles. The majority of multi species retain poisonous ankle spurs in both sexes. They lay eggs, though the eggs hatch very quickly in the cimolodontans, often within hours and the young are secreted within a pouch. Like monotremes, multis lack nipples; the babies lick up milk randomly from ventral lactation glands within the pouch.

Cimolodontan multis generally have just two molars, one lower non plagiaulacoid premolar (very rare and usually atavistic) and one serrated premolar in the mandible. The upper jaw may have as many as two even three premolars, two molars, with maybe one pair of reduced upper canines (also usually atavistic). Gondwanatherans have two premolars and two molars with one incisor per jaw row; all hypsodont to allow for consumption of very tough plant fibers as well as to deal with grit on and within them.

Lumbar ribs are rather commonplace within the clade; they often have no rhyme or reason, closely related species may have vastly differing numbers of ribs. Within Marmotabaatar, for example, lumbar vertebrate may number anywhere between zero to 7 pairs.

NEOPTILODONTIDAE (Multies, kualzaks, sajakangways and gingko squirrels)[]

Although digga-dumdums and djads are also multituberculates, the neoptilodonts of North America were discovered and described when the other two groups were still unknown, and so are the only creatures commonly called "multies". These squirrel-like arboreal herbivores are relatively common in southern North America, with two species endemic to South America. possess flexible ankle joints that allow them to turn their feet backward while climbing trees, and their semi-sprawling posture gives them an almost lizard-like appearance. These multies lack prehensile tails, and are not as agile as primates, but they are superb nut crackers, bringing their sharp lower teeth to bear and pulverizing all but the toughest seed-casings.

Many neoptilodoont species are fruit-eaters, and have formed a closely-knit symbiotic relationship with fig trees (genus p-Ficus), which has spread the trees across much of North America and assured this weird group of mammals their immortality.

NEOPTILODONTINAE[]

The neoptilodines were among the first cimolodontan multituberculates described and published in detail. Kualzaks have since turn out to be very interesting critters. Fossils are known from early Oligocene formations in Nebraska. Indicating the three clades of neoptilodontids have been around from quite some time. Kualzaks however; seem to represent a conservative generalist line that suffered a deep decline from the late Pliocene onwards. Today, all three kualzak species are found within a narrow band along the Pacific Northwest coast. One species is widespread along this band, the other two are montane isolates recently derived from a common ancestor of the aforementioned species. Kualzaks seem to be dependant on sequoia woodlands; indeed, entire colonies may live for unimaginable generations on a single tree, never touching ground. The epiphyte ecology of these trees are more than enough to support the needs of the multis.

Coast Kualzak (Neoptilodus sequoiacaeles)[]

The coast kualzak is the most widespread species of this relict clade. These multituberculates have colonies in virtually every old growth sequoia in a disjoint range extending from roughly northern California to the most of the ancient refugia islands of the Pacific Northwest. Coast kualzaks are fairly large critters, reaching a half meter and some 3 kilos in weigh. An average colony may contain between 15 to 50 individuals living some 30 to 130 meters above the forest floor. They feed on sequoia cones and seeds but most of their diet is primarily made up of the diverse leaves, seeds and fruits of the epiphyte flora in the crowns. This may range from mosses to various trees. The kualzaks will also feed on insects, eggs and occasionally vertebrates such as climbing xenos or other smaller ginkgotheres.

Male kualzaks court their potential mates with loud whines and flashes of bared skin on their tails and faces. Like all multis (and all mammals outside of Monotremata and Placentalia), they retain the ancient full color vision of amniotes, so they have brilliantly multivariate skin patterns ranging from deepest reds to full ultraviolet. Since colonies are often isolated from each other over many generations, different patterns easily develop. Colonies on two sequoia trees right next to each other can eventually develop wildly divergent patterns if enough time develops with no genetic interchange. The kualzaks are also unique among modern multis in that generally only males retain poisonous spurs used for mating fights. This is derived within the clade, as genetic studies show that both sexes retain the genes for venom, but the female's spurs are usually defunct.

The females lay 4 to 8 eggs after a gestation period of three weeks. The eggs hatch within two to five days. The mother receives no support from her mate, though all females may nest communally in a single, ancient drey or hollow. The females remain in a torpid slumber for the first two weeks in the drey with their young curled up within a nascent pouch. Afterwards, the female will go out on feeding rounds with the developing larvae secreted within her pouch.

Predation is not a large part of kualzak life. They must be wary of avisaurs and the occasional brave pusillonecatorid, but for the most part, mortality is derived from disease and intraspecific fights. However, every so many years, the colonies grow too large for their trees and many individuals are driven off due to younger age and lesser status. Predation rates skyrocket then, as these individuals are overwhelmingly snapped up as they traverse the forest floor looking for a new host tree.

GLISSAPTILODONTINAE (Sajakangways)[]

The sajakangways, more commonly known as sajas, are a clade of ginkgotheres that are found exclusively in the eastern temperate North American forests. Two species are known. Unlike the flying squirrels of HE, sajakangways tend to be mostly herbivorous, consuming seeds, fruits, nuts and the occasional insect. The gliding multis will store large caches of nuts and seeds during the autumn season to help them survive the rigors of winter. Sagas are gigantic for gliding mammals; mature individuals of either sex may easily reach over half a meter and some 3 kilos. This size gigantism is unusual, though it may have to do with the heavy, often fibrous diet of these multis. Certainly they have extensive gastrointestinal systems to deal with coarse fodder such as bark, conifer needles and even scavenged bones.

These gliding multis do not have a cartilaginous extension of their patagia; the membrane instead extends from the wrist to the ankle. While both sexes retain poisonous spurs as is typical of non-therian mammals, the males produce a substantial amount of venom during the mating and kit rearing season. Sagas are monogamous, forming life-long pairs. The males protect the female nesting in the drey or hollow created for the young for up to two months. During this time period, the male will bring food to the retired mother every 12 hours from caches throughout their shared territory.

Sajakangway (Glissaptilodus arundaneli)[]

The saja is a widespread endemic of the eastern temperate forests of North America. Multiple subspecies and regional variants are known; with several being intensively studied. Sajas are denizens of mature understories of mixed conifers and angiosperms. The highest concentrations can be found in the ancient montane rainforests of the Appalachians.

Maturation is quite long compared to other mammals of similar size, both sexes reach reproductive maturity in their third year. They don't usually begin mating until their sixth year. Both sexes usually spend their 4th and 5th years alternating between helping their parents raise their siblings and making their availability known to prospective mates in the no-man's land located along adjacent territories. Either sex may approach neighboring territories in an attempt to woo away adolescent individuals. The courting period is long, with both sexes frequently evaluating potential mates from several different areas before settling on one. Their parents are often quite involved in this process, trying to chase away suitors they deem unfit while encouraging suitors they like. The adult children have final say in the matter, of course.

When a mating pair of adult children finally bond, the parents of both will usually feed them rich fatty foods from caches such as nuts and berries. The initial honeymoon begins in the spring, the two adult kits chasing each other between their respective parents' territories and bedding down privately within tree holes. Often they will help both their own parents and their spouse's parents raise a litter of young for the duration of the spring. Then as summer comes, the couple will eventually abandon their natal territories, striking out on their own to find a new area to claim. This is the most dangerous period of a saja's life, they frequently are subjected to predation if they are forced to cross open ground or swim rivers. Should one of the newly mated pair perish, the prospects for the other are not good unless they manage to adopt themselves within a local family as helpers or dejectedly return home.

A newly mated pair that finds a suitable vacant territory sets about preparing for the next year by exploring all available food resources as well as enlargement and softening of existing dead bores and holes in trees. Extensive caches are buried in ground at the roots of trees or stored in tree holes. All caches are lined with shaved cambium to preserve them.

The first spring of a settled pair is truly exciting; they have mated in the late winter, the female has carried her young for nearly forty days. The new mother retires within a massive drey well-guarded by her husband. Eventually, she lays between 1 to 4 large, oblong eggs that she secretes within her thickened pouch folds. The eggs eventually hatch within two days, the larval offspring remain with their mother in the nesting drey for up to two months; the mother fed by the male at regular intervals. Eventually, the kits mature enough to be transferred to different nests throughout the territory. Should the mated couple succeed during their first year, they may live up to 25 years.

Saja kits are well protected, even so, they still suffer heavy predation until their 3rd year. They then are too large for any avisaur or pusillonecatorid to comfortably attack without suffering damage from snapping teeth and deadly venom spurs. The surviving kits soon begin the saja life cycle anew.

Golden Saja (Glissaptilodus aureus)[]

The golden saja is the second known species of saja, found exclusively within the Great Black Forest Swamp. This gliding multi is somewhat smaller than the sajakangway, with the largest males barely reaching 40 centimeters. These unique residents of the Lake Erie ecosystem feed on a wide variety of nuts, barks, seeds and animal matter when in season. However, the fall mast is especially important since an overwhelming abundance of swamp dwelling angiosperm and conifer trees and shrubs fruit at this time of the year. Golden sajas tend to be more crepuscular than their much larger relatives except during the full blush of summer, when the dank gloom of the understory provides a great deal of protection from the largest avisaurs.

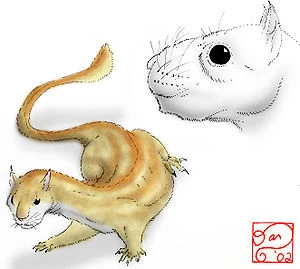

GINKOGOTHERINAE (Ginkgo squirrels)[]

The ginkgo squirrels are the most widespread of the neoptilodonts. Their epicenter was in North America, but have since spread into temperate and subtropical zones throughout South America and Eurasia. Ginkgo squirrels have tightly wove their life cycles around the ancient ginkgos. The first true ginkgo squirrels show up in early Pliocene deposits in both Eurasia and North America. They are heavily associated with ginkgo trees, often bearing evidence of gingko nuts within their stomachs.

The ginkgo squirrels seized upon the niche of ginkgo fruit eaters. Most other herbivorous animals will have nothing to do with ginkgo fruits because of their high levels of butyric acid. Ginkgo squirrels have developed a symbiotic bacterial gastrointestinal flora that enables them to break down and metabolize gingko fruits very easily. The close association of both ginkgos and these multis allows for far easier dispersion of nuts in the proper environment for ginkgos, sandy well drained loam. This companionship allows ginkgos to easily access micro ecosystems within larger areas very easily. Ginkgos are not restricted to drained loam, they can thrive in rocky or well drained acidic soils few other trees can tolerate.

The Ginkgo squirrels are not restricted to ginkgo food resources, they can feed on surrounding angiosperm and conifer tree seeds and bark. They also are quite predatory compared to most other cimolodontans, often killing and eating invertebrates and small vertebrates such as beetles, spiders, lizards, snakes and unvoles. Yet in spite of all their dietary diversity, these multis are entwined with ginkgos. They eat ginkgo pollen and subsequently pollinate trees as they move from male to female individuals within stands. The fruiting trees are visited by swarms of ginkgo squirrels as they gobble up the fruits, seeds and all. The later fall mast has the multis stripping the fleshy fruit from the seeds. The seeds are buried in caches throughout ginkgo squirrel territory. Although ginkgo squirrels will bury seeds of other trees, they prefer ginkgos above all. This habit has been a self perpetuating cycle, the multis eat and cache or shit out the nuts into favorable ground, the ginkgos grow up to provide food for the multis.

Two species are quite widespread, the Eastern North American ginkgo squirrel and the staggeringly successful green squirrel. However, there are over 30 known species and innumerable variant subspecies specialized within individual ecosystems. It cannot be emphasized enough how important these variants are. Both the green squirrel and the ginkgo squirrel likely were cold adapted variants with corresponding ginkgo tree hosts during the Pliocene.

Ginkgo Squirrel (Gingkotherium americaniensis)[]

The ginkgo squirrel is the most widespread of the American ginkgotheres. This critter can be found across the entire of the eastern temperate zone from the Mississippi river to the Atlantic Ocean north to the Great Lakes and south to the Rio Grande river and everywhere between. The ginkgo squirrel is massive, a full meter and some 5 kilos. This beautiful animal has a striking red and bluish-grey barred coat with a balancing tail.

Ginkgo squirrels mate seasonally, though well established territories may see the same alpha individuals mate for life. Both sexes court in early summer. The female gestates her 2 to 4 eggs over a period of a month before laying them. The eggs hatch within hours to a week; with the young snuggling up in the pouch folds the female develops. The male is very aggressive during this timeframe, he will sting any potential predators approaching the tree hollow utilized.

Green Squirrel (Singinkgophagus stelliomys)[]

The sole Eurasian member of the ginkgotheres is vastly widespread. The ginkgothere helped spread a novel ginkgo mutation unique to the old world . *Singinkgo* is a widespread tree that can be found from subtropics to nearly the edge of taiga forests. Fossil and genetic evidence indicates that both the green squirrel and *Singinkgo* spread into the Old World during the early Pliocene.

Like most ginkgotheres, the grayish-green and white spotted critter depends on ginkgos for at least one season. They are capable of utilizing conifers and angiosperms for a great deal of nutrition; but need the ginkgo fruits to supply most of their fat reserves for the winter

Both sexes seasonally pair-bond; though in the far south of their range, these bonds may be life-long. While the female retains poisonous spurs like most cimolodontan multis; it is the male who provides most of the nest protection. The two to maximum of four young are born once a year.

Eastern Flying Multi (Glissaptilodus arudaneli)[]

The eastern flying multi is a small, but agile tree-dwelling multituberculate, most common in the forests of the Appalachians. This multi's most distinctive features are the flaps of skin running from wrist to ankle - not as extensive as those possessed by RL's anomaluroid squirrels or phalangers, but sufficient for the animal to glide easily from tree to tree, in search of seeds to husk and eat. The eastern multi usually nests in small tree hollows, raising a single young at a time, but twins are not uncommon.

Greater Fig-Multi (Ficitherium magnus)[]

The greater fig-multi is the largest of the multituberculates, with lengths often over a meter. These sinuous, furry near-mammals live only in the p-Ficus forests of Spec's southern North America, and their diet consists exclusively of the fruit these trees produce. Like the bats of South America, fig-multis are the principal vectors of fig generation. The multis eat the fruits, and may then travel for kilometers before dropping the seeds in their feces. Thus, the trees do not only gain the spread of their species, but fertilizer for their seedlings, as well.

Golden Flying Multi (Glissaptilodus aureus)[]

The golden flying multi is the second known species of flying multi, found exclusively within the Great Black Forest Swamp. This gliding multi is somewhat smaller than the eastern flying multi, with the largest males barely reaching 40 centimeters. These unique residents of the Lake Erie ecosystem feed on a wide variety of nuts, barks, seeds and animal matter when in season. However, the fall mast is especially important since an overwhelming abundance of swamp dwelling angiosperm and conifer trees and shrubs fruit at this time of the year. Golden flying multis tend to be more crepuscular than their much larger relatives except during the full blush of summer, when the dank gloom of the understory provides a great deal of protection from the largest avisaurs.

TAENIOLABIDIDAE (Digga-dumdums and afancs)[]

Like so many other groups of Specworld creatures, digga-dumdums have proven frustratingly difficult to classify. A casual observer would probably place the lumbering digga-dumdum as a woodchuck or badger, but any further inspection of these heavily-built, deep-faced mammals would convince an observer that they are in no way related to these Home-Earth groups. A great deal more examination would be necessary to ascertain exactly what these creatures are.

Taeniolabidid teeth are very strange, indeed. The incisors, upper and lower, are the same size and shape as the surrounding teeth, while the grinding teeth toward the rear of the mouth are greatly enlarged and obviously mutltituberculate. These teeth are very deep-rooted, and grow constantly throughout the life of the animal, enabling it to tackle a range of abrasive foliage. Taeniolabidids, then, do not nibble or gnaw like xenotheridians, but chew their food rather like Home-Earth pandas.

Taeniolabidids probably evolved during the Paleocene or Maastrichtian in North America as woodchuck-like creatures. In our home time-line, these and all other multituberculates went extinct at the end of the Eocene, but unlike their counterparts in RL, Spec's multies failed to vanish and continued to thrive through the Cenozoic. By the Oligocene, the taeniolabidids had spread across Eurasia, and possibly to Africa, where they swept aside a number of early rodent-like lineages, only later to be pushed into the background (at least in some niches) by the xenotheridians. The Great American Interchange of the Pliocene brought taeniolabidids into contact with the burrowing xenarthrans, but there seems to have been little conflict involved in this particular mix. Digga-dumdums are almost exclusively herbivorous, while the xenarthran bullettes and armadillos are generally insectivorous, so the two clades have managed to coexist peacefully.

MELONYCHINAE (Digga-dumdums)[]

The digga-dumdums or "diggadums" are bombastic sized burrowers of Eurasian and North American grasslands. Digga-dumdums are huge for burrowing mammals. They were mostly small 4 to 8 kilo critters during the Cretaceous and the Paleogene. During the early Neogene, they expanded into larger 10 to 15 kilos sizes in far northern latitudes and at high altitudes. However, the onset of the Pleistocene Ice Ages has been a true boon for the clade, with some 18 described species. No modern day representative is less than 40 kilos adult size, 50 to 70 kilos is common and one species is a staggering 110 kilos. It is believed that the diggadums are part of the herbivorous mammalian and maniraptoran radiation that attempted to fill up the niches vacated by the scaly ornithischians and sauropods.

Like all other multis who dealt with the naked spaces, they responded by burrowing underground. Digga-dumdums eat grasses and herbs within a few hundred meter radius of their burrows. Digga-dumdums tend to form colonies of up to 100 individuals of varying ancestry. During especially productive grassland years, the colony may have so many members hollowing out tunnels that the ground collapse and a wetland sink forms. These marshes force the digga-dumdums to migrate to new territory; resulting in heavy predation.

Females come into season during late winter/early spring. They have a 20 to 40 day gestation before laying between 2 to 6 oblong eggs which hatch within several days. The young remain with their mother for nearly five months underground before venturing into the surface world.

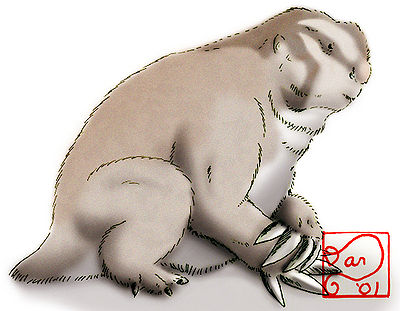

Digga-Dumdum (Melesonyx bombastus)[]

A traveler in the northern prairies of Spec's North America is likely to see (or perhaps trip over) a number of mounded burrows that dot the landscape like miniature calderas. These burrows are the result of the labors of the prairie's largest mammal, the digga-dumdum.

Digga-dumdums are taeniolabidids, a group of enigmatic multituberculates that have lived in North America since Mesozoic times. They are heavily-built and placid, with deep faces and powerful, ever-growing molar teeth that can pulverize even the toughest grasses. These creatures are huge by the standards of Specworld mammals, the largest bull males measuring a meter and half from snout to tail. They generally burrow under the soil, eating tubers and grassroots, but will often venture above ground to graze upon the grass.

When predators threaten, a digga-dumdum will rear onto its hind legs and swipe at the attacker with powerful digging foreclaws. The claws of these normally peaceful herbivores are quite capable of ripping the face off of an unwary drak or errosaur, and the mammals usually go about their business unmolested.

Like most taeniolabidids, digga-dumdums are monogamous, forming life-long couples during their third year and then constructing a permanent warren where they can live for another decade. Often, young digga-dumdums will expand upon the warrens made by their parents, until an entire field is riddled with meter-wide holes. Of course, the entire ground sinks during the next heavy rain, creating a temporary "digga-bog" and forcing the architects of the disaster of move elsewhere. It is during such moves that the mammals are most vulnerable to predation, and their cycles of growth, excavation, flood, and retreat have become an intimate part of the ecology of the grassland.

Mahmot (Melonyx arctogigantis)[]

The mahmot is far and away the largest of the digga-dumdums. These 110 kilo critters spend most of their lives hibernating during the harsh arctic winters. They finally emerge during the May spring season to nibble on dry grasses and prepare for laying. These digga-dumdums are both weed and climax settlers. They can often be seen along side lummoxes tearing up the few remaining bare grounds this late in the current interglacial. Like the segnosaurian lummoxes, mahmots chew up mosses and scrape away soil bare; to be dried by arctic winds and provide the basis of a new Arctotitan Steppe. Mahmots are little different from their more southerly cousins in one aspect however.

They eventually become so numerous that part of the local colony's territory may sink and form a temporary wetland or "Mahmot marshes". This results in a mass exodus to new uninhabited territory; during which time predation is rampant, from baskervilles to the gigantic saber sues.

Mahmot marches may go quite far, occasional super productive years result in mass migrations of literally thousands of the beasts across the steppes. Those marches close to the Arctic Ocean may often swim for may miles out to sea. These animals usually drown or are predated upon by selkies and emperor seaguins. However, a few survivors might chance upon a barren island populated by little other than arctic dogbunnies and lummoxes who have crossed over on winter ice. The arrival of mahmots is a huge boon for the other two weed herbivore species. The mahmots will eventually tear up so much sand and rock that grasses will settle on the now dried soil base. The further grazing interactions between the three species results in a rapidly spreading cover of grasses and forbs. Such interactions are crucial for progressive climax species of plants and herbivores. Even though it has just been a few thousand years since the last Glacial, Spec's Artic lands are far richer in diversity and productivity than anything known on HE. The ecotype of Arctic Barren Ground simply does not exist except on very isolated islands.

CASTORIBAATARINAE (Afancs)[]

Sometime during the Miocene, a group of taeniolabidids moved from the grasslands and prairies into the marshes and swamps. In

doing so they triggered a quite successful radiation. Often likened to the beavers of Home-Earth and the mangrove beavers of Spec, their bauplan is more like that of an enlarged, sprawling muskrat, along with the usual suite of unmistakable anatomical features that betray that they are multituberculates. The animals swim with enlarged, webbed hind feet, and their bare, laterally flattened tails, like a weird cross between a desman and a platypus. In the males, the tail bears bold bands or blotches, colored bright yellow, orange, or red in the breeding season, being beige the rest of the year; it must be kept in mind that multituberculates are not red-green blind or color-blind like most eutherians and monotremes are.

The afancs gain their name from the legends of giant Welsh water monsters resembling beavers. Like Home Earth's beavers, most afancs, with the exception of the Florida marsh afanc Floridabaatar parvus, build large dams and lodges from plant material. However, the purposes of these structures differ in striking ways. In the case of beavers, these lodges are used as denning sites, as well as creating good habitat by damming rivers and flooding the local forest. Afancs, however, also use them as decorative bowers. Male afancs in breeding season construct giant mounds of reeds and branches in the middle of ponds and lakes, harvested from the surrounding woodlands. These are cooperative affairs, with 2 or 3 males pitching in, more in particularly rich habitats. During early summer mornings, males will display to the local females, waving their brightly banded tails in the air and strutting over the mound. Males will often also try to evict their fellow competitors from the mound (once it's complete).

Afancs seem to have exploded in diversity during the early Pleistocene in Siberia. Today, the two genera of Castoribaatar and Floridabaatar are rather small muskrat sized critters. The former quite common across the Holarctic, with several species and regional endemics ranging south into subtropical zones such as the Levant and the Chihuahuan regions. The other two species within Mortibataar and Allocastoroides are gigantic, reaching up to two meters and 180 kilos.

Eurasian Afanc (Castoribataar potteri)[]

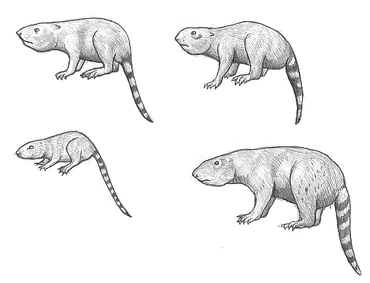

Top left: Eurasian afanc. Top right: Lesser afanc. Bottom left: Greater afanc. Bottom right: Florida marsh afanc.

The Eurasian afanc is a typical castoribataarine. Little larger than a muskrat at 2 kilos, these animals can be found across almost all of temperate and boreal Eurasia wherever permanent water exists. Young males typically band up with their relatives or other vagabonds attempting to either create a new afanc pond or evict the older residents of an already established territory. They busily work at shoring up the dams, lodges and bowers to attract the attentions of females.

The pond is eventually visited by up to ten females who caustically judged the preening males. The former work mates often violently tear and stab into each other; attempting to drive each other off. Deaths among the males are high during this stressful period and usually just two or three brothers or close friends manage to come through relatively unscathed. The females seem to take all this in stride, even being amused at times. The violence soon settles down and the remaining males again strut (though much more maturely and wisely it seems) before the females. The feigned disinterest of the girls is actually calculating. They wait to ensure that the remaining males are powerful enough to defend the territory, since they will raise the kits alone within it for several months.

Eventually the dominate male gets to have his choice share of the mating, but the females are usually quite promiscuous. They will mate with all the resident males to ensure that their kits will stir paternal affection and defense no matter what. After the early spring mating, the females will construct a nest of mud and twigs, usually high up in a tree. The nest is much like a more enclosed version of a squirrel drey, being a spherical structure of plant matter cemented with mud. The inside is filled with dry bedding, mostly shed under fur. The 2 to 4 eggs are laid after a gestation of roughly a month, the eggs hatching out within a week.

The kits clamber out of their drey by late summer to join their mother at the pond. The males welcome all the females with their young, even doing baby-sitting duties while the mother forage for water plants, piths and the occasional insect or slow fish. The winter season has all the males, females and young within one or two lodges in winter torpor. They will occasionally wake up to harvest stored corms and barks or to defend the nascent clan from predatory gatordogs. When spring arrives, the yearling kits disperse to seek out their fortunes elsewhere.

Horrid Afanc (Mortibataar tolkieni)[]

The most famous of the afancs are the horrid afancs of Europe. This giant species is the largest known, reaching the size of a selkie. The animal responsible for the name "afanc", male horrid afancs are known to be highly territorial, and will attack any perceived threats to their breeding bowers, whether they be resting flankers, draks, or curious cientists. Male horrid afancs usually only create bowers, but what spectacular constructions they are, often up to 4 meters tall with fringing rays of twigs up to 2 meters to lead their prospective mates to the dancing, displaying male flashing his tail with brilliant, variegated neon colors.

Horrid Afancs are mostly reclusive outside of the breeding season. A single male will control a territory with two or three females and their kits. Since they do not create dams, males will set up shop in the ponds of their much smaller relatives. They do not compete much since Horrid afancs prefer shoreline reeds and grasses that the astoribataarines mostly avoid. During the winter, horrid afancs will bust open ice holes to crawl out onto shore for tree bark and root around the pond bottoms for corms. Horrid afancs also have another strategy, they turn carnivorous, eating sluggish fish, crustaceans and even turtles during this lean season. In really harsh years they may even attempt to devour their much smaller cousins.

Wishpoosh (Allocastoroides aquatilerus)[]

The wishpoosh is a gigantic afanc of North America. It is the largest afanc by far, with exceptional females reaching over 200 kilos in weight. Wishpoosh differ from all other afancs in having life-long monogamous relationships, both sexes raise the young within massive ponds which are better described as lakes. Indeed, in the American Southwest, some rivers have regular dams punctuating them like clockwork. These dams hold back waters that spill into floodplains many miles on either side, providing the richest feeding grounds in all of the North American Desert realm for a staggering diversity of life-forms.

Wishpoosh may be found across virtually the entire of frigid to subtropical North America. They are true Spec beaver analogues, writ large. Male wishpoosh afancs leave their natal territories around the age of five. The lucky ones find vacated ponds or new territory to develop. The dams are constructed first; these are truly massive and occasionally result in a mile or more wide lake if the floodplain is spacious enough. Then he constructs his lodge with food stores. He often doesn't even construct a bower until the second year, spending his first year alone.

When he does build the bower, it is a sight to behold, fully as massive as a horrid afanc's it is often decorated with shiny objects such as black feathers reflecting ultra-violet (easily recognized by all multis) mollusk shells, egg shells, bright flowers, seeds, bones and so on. He will go to the shoreline to utter a deep barely audible roaring groan that is detectable for many miles around by any other wishpoosh. Other males may attempt to oust him. These usually result in failure, for a male who can maintain his pond is usually powerful enough to keep it.

Eventually, passing females pick up the lovelorn calls and come courting. They first size up the territory before they enter. The majority of afanc females will not enter unless all requirements are met. Unlike other afancs, however, once the females enter, the male wishpoosh calls the shots. He has already provided the habitat, food and lodge. Male afancs usually disdain female attentions until several have simultaneously arrived. The situation is often the reverse of other afancs. The only real selective quality female afancs have been able to show are selection of territory and the luring of wandering males into the territory of an established male to judge the resulting violence. Aside from these quibbles, it is the females who are in deadly earnest with each other, since the male will usually only devote resources to one mate. A female may mate with any male, but the success rate of reproduction by herself is so dismal, it is not worth the bother.

So for once, a male afanc sit back idly while the females rip into each other. Eventually one (occasionally two, usually sisters) succeed in driving away all the others. She then begin an elaborate courtshipritual with the male. The successful female will remain his mate for life, helping him drive away all intruder males and he will help her drive away all intruder females.

The mothers construct a birthing lodge which the retire into. The kits are gestated for nearly three months before being laid in eggs of 1 to 4. The eggs hatch with two weeks. After four months, the kits are ready to face the outside world. The more northerly ranging wishpoosh kits usually remain in the winter lodge before finally seeing sunlight seven months later in spring.

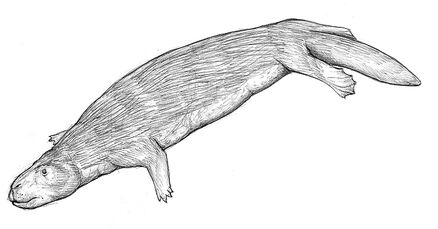

THALASSOCAMELIDAE (Gloops and kelp cows)[]

There must be something strange about the sea that attracts mammals. In our timeline, whales, sea cows, seals and certain otters live off and largely in the deep blue, not to mention the extinct desmostylians; in Spec, cancridonts and selkies have taken to the oceans. The fertile waters of South Australia were found to hold yet another funky marine mammal, the gloop, which is associated with marine, coastal, estuarine and marsh faunas. The gloop family includes the kelp cow, one of the largest marine mammals known in Spec.

The gloops are generalist cold-water algae and kelp grazers that first appear in the fossil record in the Oligocene. These multituberculates seem to have had their center of origin around Antarctica, certainly the presence of the latest Eocene Merididugongia, a 30 kilo seashore browser of kelp and algae on a newly discovered deposit located only on Spec's Seymour Island indicates so. The Oligocene and Miocene saw the family radiate across the sub Antarctic as far north as Australia and New Zealand. The Pliocene saw algae browsing tropical forms and the subsequent evolution of the Northern Hemisphere kelp cows.

THALASSOCAMELINAE (Gloops)[]

Gloops are the most widespread thalassocamelids. They may be found in seasonally migrant herds around the Antarctic Ocean and range north into the tropics and cold Atlantic Ocean. Some 6 species are currently recognized. Most are generalist algae browsers, though the north atlantic species specializes in kelp and sargassum weed.

Gloop (Thalassocamelus thieliei)[]

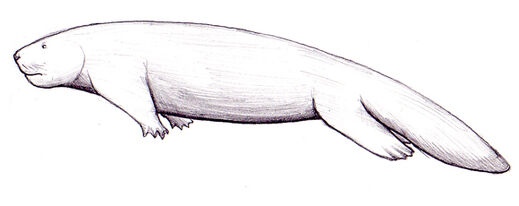

The gloop ranges from the coastal waters of northern Aotearoa to northern New South Wales, sustained in these bountiful waters fed by the southern ocean. Gloops have a large, camel-like head, stubby, clawed forelimbs, and a tapering, cylindrical body much like a sea cow. Their tail is deep, flat and powerful, but relatively short, and their back legs are paddle shaped; they swim with horizontal undulations much like a sea otter. Gloops have a covering of long wiry hair along the back; this not only serves as insulation but harbors green algae, small crustaceans and snails (some beneficial, some parasitic, some commensal). They also have a thick layer of fat for buoyancy and extra insulation, and their belly is covered in very thick, tuberculous calluses that protect them from scraping rocks while feeding and even sometimes from shark attack. These animals feed on a wide range of marine plants, from tender red algae to seaweed, cold water Spec "sea grass" and kelp, which they crop with their thick, muscular lips and cut with their large incisors.

Gloop breeding behavior is amongst the strangest of Spec's Mammalia. In the breeding season (June - August), females and males congregate around river mouths, the younger first-timers following the elders there in single file (called "caravans"). Upon arrival the males will pick and fight for a choice area upstream the further upstream you are, the calmer the water, and the harder you have fought to get there. Naturally the stronger males are positioned further upstream. The males choose their spots in this way to "serenade" the females with their loud belch-like above-water calls of "GLOOP!! GLOOP!!" punctuated by long strains of jowl-shaking calls. The females travel upstream past the throngs of belching, blubbering males until they find a male that they see fit to sire their young. This bizarre procession, as well as the convoying and lek fighting behavior that precedes it, is a singularly bizarre spectacle.

The females travel upstream into estuaries to give birth. The solitary calf (rarely two) is dependant upon its mother for nearly a year. Out of breeding season these animals tend to either live alone or in loose aggregations depending on resources. These animals can live for as long as 40 years or so and grow to 3.5 meters in length.

Mediterranean Gloop (Thalassocamelus suboriotethyis)[]

Unique to the Mediterranean Sea, this animal is a typical tropical water gloop. They slurp the algae growing on vast beds of inoceramid clams and coral reefs. Often seen alongside duckgongs, the two clades never come into conflict, because one feeds on sea grasses, while the other prefers seaweeds and algal mats.

BOVIGALINAE (Kelp cow)[]

The Kelp cow is the only member of its clade. This is truly an exclusive kelp feeder. Compared to other gloops, kelp cows are rather archaic in certain details of their teeth and skull. However, they are more derived in having lost the ancestral belly tubercles and developing a more pachyostylic skeleton, especially around the ribs.

Kelp Cow (Bovigale memorium)[]

The kelp cow is an impressive 6 to 7 m long beast, weighing as much as a moby duck. It is found primarily in the kelp forests of the northern Pacific ranging from The Baja peninsula to the Sea of Oshkosh, hugging the shallow waters. Local Alaskan and Kamchatkan populations sporadically range into the Bering Sea during the summer season.

Kelp cows subsist mostly on kelp, which they process with their formidable dentition and digest in their extensive stomachs. Kelp cows swim with powerful up and down strokes of the lower torso, which moves the paddle-like tail and hind limbs. Kelp cow forelimbs are stubby, with clawed fingers used to grasp large amounts of growth.

These animals possess both a large amount of blubber and a reasonably thick coat of of smooth, slick hair. Kelp cows will mainly browse on the floating rafts of kelp when they are in season, but observing kelp cows feeding on whole belts of kelp is both intriguing and amusing. Firstly, the mighty beast dives down and severs the kelp from its holdfast, then the animal returns to the surface and grasps the belt as it eats, much resembling a mouse eating a whole strand of spaghetti.

DJADOCHTATHERIA (Djads)[]

Burrowing djads form the most diverse group of multituberculates on Spec. Although somtimes similar in appearence to the digga-dumdums, these burrowers are only distantly related, with roots that reach far back into the Cretaceous, when they were confined to Asia. Djads appear to have reached North America in the early Eocene, but didn't become common until later, when they swept into Europe in the Oligocene and northern Africa in the Miocene. Djads live on and in the ground, like RL's ground squirrels or prairie dogs and may be found in even the smallest grasslands throughout the Northern Hemisphere and much of Africa. Some species also dwell in temperate forest when the soil is not too damp. Despite their abundance, most djad species are difficult to find, because they all dwell in extensive burrows. They have good eyesight and are very alert, so the nosy spexplorer rarely sees them when they scurry about between the entrances of their burrows, running lizard-style with wide side-to-side swings or galloping croc-style. Especially in the gregarious species, individuals may be seen squatting on their hindlegs and tail and watching for danger.

Djads are more exclusively herbivorous than RL's squirrel's, presumably because of their multituberculate cheek teeth, which allow them to rasp grass, grass roots, all kinds of seeds and much other vegetable matter to powder; they frequently use their multituberculate enlarged premolar to saw open seeds and nuts in a way no rodent or xenotheridian can. In seasonally cold or dry regions, many species collect seeds and hide them for the winter, thereby helping many plant species in their dispersal.

Steppe Djads (Citellobataar sp.)[]

Occurring throughout the frigid to warm steppes of Eurasia, the 30 or more species of steppe djads are a important prey for a variety of maniraptorans and mammalian predators. Female steppe djads gestate for 25 days with around 6 eggs in a grass-lined burrow. The eggs hatch in a few days and within two to three months the young are off on their own. Males are smaller, and distinguished by a pale, almost white pelage, with tawny feet and mask.

Arctic Steppe Djad (Citellobataar borealis)[]

This is a wide ranging holarctic species found exclusively in Arctotitan Steppes. The large size (500 grams) and specialized hibernation patterns of this critter may explain their rather northern distribution. These djads are climax settlers. Steppe Djads require at least two feet of dry soil for hibernation Large colonies of over thousands of individuals indicate the area has been a rich grassland for a very long period. Indeed, one can often dig down up to six feet before hitting permafrost. The late spring on the tundra steppes has flashes of color as the small males court their larger females with flashes of bright orange and yellow throat fur.

Western Steppe-Djad (Citellobaatar spermophilus)[]

Occurring throughout the steppes of Asia, steppe djads are a important prey for a variety of maniraptorans and mammalian predators. Female djads give birth to around 6 young in a grass-lined burrow, and within a month young are off on there own. Males are smaller, and distinguished by a pale, almost white pelage, with tawny feet and mask.

Eastern Chipmunk-Djad (Tamiabataar striatus)[]

Common throughout most of the deciduous woodlands of Eastern North America, chipmunk djads are frequent visitors to the camps of Spec explorers, pilfering whatever food is laying around, to complement there normal diet seeds, nuts, and small invertebrates. In appearance, chipmunk djads are with the striped backs and tawny pelage of Home Earth chipmunks, which gives the small multituberculates camouflage as they scurry about the forest floor. Unlike real chipmunks though, chipmunk-djads have sprawling limbs, as well as a more “sausage” shaped body, in common with their djad kin. Tamiabataar is a specious clade; despite only two species in the eastern half of North America, as many as 40 other species inhabit the mountains of the west, some species confined to single peaks. In addition, the genus also ranges down south into the mountains of Mexico, and several species occur in Japan and East Asia.

MARMOTABATAARINI (Marmojads)[]

The marmojad nomer is used informally for well over 200 described species of various burrowing cimolodontan multis. They can be found across Africa, Eurasia and North America. In published literature, the name is strictly used for the members within Marmotabataar. The study of the clade is still rather nascent, there may be a few surprises in store.

Living high across the mountains of Eurasia and North America, the 30 or so species of marmojads are medium-sized multis, dwelling in colonial burrows in the slopes above the treeline. The presence of marmojads can most easily be told by the mounds of grass left to dry among the rocks, to be later stored underground as winter provisions. Like all marmojads, the males have more dramatic pelage than the females, having white-gray bodies, with black faces and chest. These djads have few predators at such high elevations, mostly kochillas, pusillonecatorids and avisaurs, for which the djads have distinct alarm calls.

Alpine Marmoset-Djad (Marmotabaatar alpinus)[]

Living high in the alps, with related species across the mountains of Eurasia and North America, alpine marmoset- djads are medium sized djads, dwelling in colonial burrows in the Talus slopes above treeline. The presence of marmoset-djads can most easily be told by the mounds of grass left to dry among the rocks, to be later stored underground as winter provisions. Like all marmoset-djads, The males have more dramatic pelage than the females, having white-gray bodies, with black faces and chest. These djads have few predators at such high elevations, mostly predatory pokemuroids and alpine anti-eagles, for which the djads have a distinct alarm call.

Belchpig (Marmotabaatar monax)[]

Spec’s own groundhog, sometimes known as the Chuckie, is one of the largest djads in the world, massing upwards of 8 kilograms in weight. A burrower that inhabits meadows and woodlands edges, the belchpig spends nearly the entire summer and fall fattening itself on nuts and acorns, in preparation for the long hibernation ahead. One of the most distinctive characteristics of this species is the lack of bright breeding colors or displays among the males; this is believed to be an adaptation to not drawing the attention of predators, given its unusually large size for a djad, and it rather slow waddling gate. belchpigs never stray far from a convenient burrow. However, to compensate for this, the males have a unique and loud call, most reminiscent of a human belch. These features suggest a very basal position within the djads, as most are mute; either that, or djads might not be as mute as previously believed. This call is used to attract and show off to females, and belchpigs can most easily be observed on mounds in front of there burrow in late spring, letting off their sexy, loud burps for all females to enjoy.

Striped Grass Djad (Xerobaatar erythropus)[]

Closely related to the Kilmanjaro marmoset-djads (which contrary to name aren’t closely related to the Holarctic marmoset-djads), this species shares many of the same habits and reproductive behavior of there mountain brethren. However, this species is more widespread, found throughout the Savannahs and scrub of Sub Saharan Africa. Living amidst the long grass, striped steppe djads colonies construct large networks of tunnels within the grass, along with burrows, whose total range may equal a football field or more in length. They may be readily identified by there checkerboard patterns of dark stripes over a tawny pelage. In addition, during breeding season the males turn a chocolate brown in color, with rufous underbellies and noses.

Kilimanjaro Marmoset Djad (Xerobataar altalpinus)[]

The marmoset djads of Kilimanjaro, are 40 cm multituberculates may be found among the roots and low stems of theirhome mountain's alpine meadows. These djads feed mostly upon the milky seeds of grasses and use the stems to build ball-like nests. The nests are usually located in deep within grassy tussocks and are used by females to give birth to a litter of usually 6-8 pups. The nests are mostly found empty by scientists as mother djad retreats to their underground galleries as soon as the babies are born.Male marmoset djads are often smaller than females (10 cm + tail; 15 cm + tail), but are usually much vivid in coloration, as their fur is mainly fiery golden with a mix of rusty reds and browns, in contrast with the earth brown and ochre, bulkier female. Djads are fiercely territorial and, like many multituberculates, use visual symbols as the basis for their displays. Although these djads are virtually mute, their broad ears are very sensitive to sound.The isolated microhabitats of Kilimanjaro have lead to a number of X. altalpinus subspecies, each inhabiting a different segment of the mountain's slope. These varieties range from the large, rock-colored X. a. hyracoides to the silver-white X. a. fulgidus, which inhabits the frozen lands of the mountain's central plateau. Common across the plains of North America, white-tailed prairie djads live in large communities, digging extensive networks of tunnels deep into the grassland soil.

Prairie Djad (Cynobataar candidicauda)[]

Also known as white-tailed prairie djads, the prairie djads can be found across the central grasslands of North America in large colonies of several thousands. They are not quite as numerous as HE prairie dogs but tend to be much more densely packed, thus resulting in greater overall biomass. The animals are heavily preyed on by a wide range of critters from mammalian tokalas and pusillonecatorids to dinosaurian avisaurs and mattiraptors.

Prairie djads have polyamorous breeding systems encouraging the local males to treat all kits as their own. This allows females to leave her offspring much earlier than most other djads to forage aboveground for food. Prairie djads have white tails with interspersed edging fur that reflects ultra-violet, a good warning system. These little critters actually flash different tail patterns for different predators.

Chinese Forest-Djad (Sinobaatar aenigmaticus)[]

A native to China and Liaoning forested areas, the Chinese Forest-Djad will make its home near dead trees in the forested areas of China. These burrows can go one or miles and miles underneath the forests. These creatures have also been documented, making them quite an enigma among the Specresearchers. These creatures are still awaiting more research so that we can get a full understanding of these enigmatic animals. However, as of now, recent observations show these creatures are known to live in large family groups.

Western Tunneling-Djad (Ameribaatar cynomysmimus)[]

A native to the deserts of western North America, the western tunneling djad is a common mammal in these area. These small creatures get their name from their behaviors, they are known to dig deep tunnels in order to escape the harsh desert sun and predators in the area. This tactic works against most predators with the exception of snakes. When that tactic fails, it will resort to using its claws to defend itself from its serpentine attackers.

Churchill’s Djad (Albionbaatar churchilli) []

The only species of Djad native to England, the Churchill's Djad gets its name from its reputation for being fearless and persistence in fending of any sort of predators in the area, even in the case of large predators like the avisaurs and younger Grundel. These small mammals are known to dig a network of tunnels through the thick British soil, in order to escape larger predators. These creatures are active until the winter season when they have been known to hibernate.

Portugese Mountain Djad (Proalbionbaatar montanus)[]

The only member of the Djad's native to Portugal, and possibly Spain, these small creatures a native to the mountains regions in the area. This particular species is known to live in this environment for reasons unknown at the moment. Keep in mind, these are a recently discovered species so not much is known about them at the moment.

NECOBAATARIDAE (Death multis)[]

"True" multituberculates are an extremely rare fossil find in HE South America. No examples are known earlier than the late Cretaceous and of these only Argentodites and Ferugliotherium have been assigned with any hint of confidence. The former seems to be a cimolodontan, the latter a "plagiaulacoid". The "true" or Cimolodontan multituberculates never seemed to have had much success outside of their northern hemisphere stronghold during the Mesozoic. HE lost its SA multis during the end K events. Spec however, is a different story.

The cimolodontan multis remain rather rare throughout the Paleogene. A few tiny mandibles and vertebrate are known in scattered deposits, but they are not really helpful and categorizing except the teeth seem to share the same prismatic characteristics as *Argentodites*. Although some tooth structures seemed to indicate relationships with Plagiaulacoidea, they are very similar to the Oligocene *Archonotobaatar*, which, with a near complete skeleton, is regarded as a close sister group to the late K South American "true" multis.

It seems that both "true" multis and the archaic plagiaulacoids were gradually displaced by the gondwanatheres. Eventually the last plagiaulacoid fossils disappear in the Pliocene. The fate of the native cimolodontans followed a different path.

Despite some calls that claim modern South American multis are actually a fairly recent rafting arrival, the disparate fossil record and subsequent genetic studies indicate they are quite distinct from all other cimolodontan multis. There is no indication however, that they are plagiaulacoid multis either, as both the genetic and morphological evidence shows.

Whatever the case, the Neogene Andes formation saw a radical departure from typical multi behavior. *Nefastobaatar* is the earliest of the necobaatarids. This late Oligocene fossil is virtually identical with the modern day forms. The plagiaulacoid molar has turned into a sharp carnassial like blade, the remaining premolars and molars are also modified into shearing cutters. The forelimb structure has massive insertions for muscles in the deltoids and humerus. The incisors are typically multituberculate, except grown long.

These last South American multis remain fairly rare montane and cool Patagonian taxon until the late Pliocene. They never exceed a HE stout in size during this time. The necobaatarids sailed through the turbulent times of that period and established themselves as the principle endothermic microvertebrate invertebrate predators of South America. The rare dryolestids are nocturnal gliding symbiotes, the metatherians are arboreal folivores and browsers for the most part, the xenarthrans are weird specialists and the remaining terrestrial crocodiles are all tropical predators mostly in the 1 to 4 meter range.

Necobaatarids fill a huge range of niches akin to the pusillonecatorids and zams in the northern hemisphere. These terrors range from 70 grams to the horrifying 20 kilogrammed Epunamun *Runaabataar ferox*. The necobaatarids have pissed the pants out of collectors in the Americas. Both sexes retain venomous spurs used for subduing prey and deterring predators. The venom is described as initially excruciating, then oddly blissful. One can only imagine what the typical prey of these killers go through, as the primary grappling sting is followed up by a decapitating throat bite. Currently, the properties of the venom are being studied for possible medical benefits, such as relieving arthritis pain. Herbivorous ancestry aside, these multis have emulated the proud tradition of HE diprotodont marsupials and grasshopper mice in being exceptions to themrule.

Necobaatarids seem to have held all but the largest pokemurid chillas at bay from South America. Draks, errotyrants and metacanids remain powerful enemies, capable of shaking or stabbing them to death before they utilize their spurs. Still, these multituberculates have spread into Central America, where ironically enough, they primarily prey on their herbivorous cimolodontan relatives as well as poisonous tweeties.

Reproductive care varies among the necobaatarids. Most species have the female burrowing into a lined nest to lay her tiny eggs after a 30 to 50 day gestation period. She curls up her cloaca to deposit the eggs directly into her pouch. The eggs hatch very quickly, often within just two days. The undeveloped offspring are nestled within the pouch for the remainder of their nursing period as the mother goes out to hunt. Weaning involves ejecting three to five month old tykers into a safe burrow while the mother continues to provide for her ravening brood. During this time, the offspring tumble and play with each other, learning social graces and developing skills for the hunt. Mother permanently switches them to a meat diet no later than six months. The young death multis start hunting with their mother often even earlier than this time frame, but certainly by their seventh month, they are already well-versed killers.

Perhaps one of the most distinctive features of these multis is the naked skin on the undersides of their tails. Brilliantly colored, they are prominently flashed at predators as a warning accompanied by staccato hisses. Venom is metabolically taxing to make and it is much better to use as a last resort. Both sexes also flash their tails in ritualized displays during the breeding season. When not in threat mode, the naked skin is covered by overlapping fur.

RUNABAATARINAE (Epunamuns and Gurviloos)[]

These are the largest of the necobataarids and the most feared. Several spexplorers have died at the spurs and jaws of all 5 species of these notoriously bad tempered monstrosities. Admittingly, those folks had been disturbing the brooding mates of protective males. Still, epunamuns have been known to aggressively pursue observers over long distances "escorting" them out of their territories. Gurviloos are infamous for stinging divers for no apparent cause, resulting in the necessity of thick diving suits throughout a great deal of South America.

Why the runabaatarines are so aggressive to humans is not known. They rarely show the same behavior towards swimming dinosaurs or mammals known to prey upon them. Some of the more spiritually inclined folks say they are the incarnations of the blood-thirsty gods that once ruled HE Mesoamerica, having a bit of fun at our expense. Possibly it is a reaction to spexplorers unknowingly venturing near nests.

Epunamun (Runaabaatar ferox)[]

At 20 kilograms, this is the largest of the necobaatarids. Epunamuns are the wolverines/kochillas of the South American Andes. These venomous mammals use their thylacoleoid dentition to savage everything from small gondwies and xenos to nandrakes, spelks and un-gulates three times their size. Epunamuns have unique, loose, cartilaginous vocal cords that allow them to voice massive chilling roars. They are found throughout the higher ranges, though the altiplanos are their main stronghold.

Epunamuns have rather elongated pedal carpals that allow

them to make significant leaps like a demented rabbit. The presence of

thick fur around large tapered ears help to facilitate this

appearance. There is an isolated population of Epunamuns R. ferox antioch found

in the highland moors and peaks of a region that is the Antioquia

department of Columbia on HE. The local spexplorers half jokingly call

it el conejo asesino. While it doesn't slaughter knights, it has

been known to severely injure curious parties.

Venom is a precious resource for an endothermic animal. Epunamuns prefer to slice through tissue and bone, saving the toxin for larger prey or predator deterrence. Watching a 60 kilo juvenile trunk lip die at the spurs and shearing jaws of an epunamun is a terrifying experience. It is a quick but ignoble end, with extreme shock quite obvious in the poor beast's last moments.

This destruction of the local fauna does serve a purpose. Ravening kits newly hatched from their eggs need to be fed by mother. Father provides with as ample a supply of meat as he can procure. The 2 to 3 kits require intensive care for several months from both parents. It will be at least a year before they are mature enough to disperse out of their natal home range.

Gurviloos (Locustafeles sp.)[]

These aquatic necobaatarids might have been the principle endothermic predators of South and Central American waters if selters and cancridonts had not invaded within the last 5 million years. Selters aggressively kill and eat them whenever the opportunity presents itself. Still, they have an impressive range. Terra del Fuego to southern Mexico, these piscivores have done well. Gurviloos have elongated skulls with sharp incisors that allow them to seize fish with a minimum of struggle. Their venomous spurs are used mainly for defense of territory and kits.

Gurviloos may enjoy fish, but they don't pass up delectable tetrapod prey such as mangrove beaver kits and waterfowl. Indeed, some regions see up to half of mangrove beaver kits stung to death by these hungry multis. Dinosaurs aren't exempt either, many anseriformes and even the wading chicks of viriosaurs and duckgongs may disappear in a flurry of bubbles.

The long maturation period of gurviloos often sees last year's kits helping their parent raise the current brood. Compared to the tight knit families seen in selters and cancridonts however, these adolescent kits often are eager to oust their parents or leave as soon as a potential mate presents themselves.

Ogoun (Locustafeles terrastrialutra)[]

The ogoun is a gurviloo that has reacquainted itself with terrestrial life. Instead of whipping like a lizard through water, it whips like a lizard on land. This 4 kilo multi is a descendant of rafted desperados who found paradise in Cuba some million years ago. They subdue the native game fowl, mammals and odd small archaic non avian dinosaurs and reptiles that are found in abundance on the isle.

Males fiercely defend their brooding mates for the month of incubating and initial nursing. The young soon are sequestered in hidden dens throughout the territory while both parents hunt for food. Ogouns are an interesting part of an ecosystem that contains a haphazard mix of incredibly ancient and occasional neuvo ratis fauna.

Chactlaloc/Arikute (Locustafeles amazonis)[]

A cosmopolitan species ranging from Mexico to the Pantanal. Spexplorers hate them. They are aggressive for unknown reasons to any human entering their territories. Full diver suits are required to not be paralyzed by the excruciating pain their venomous spurs can cause. Only recently has it been realized that quiet backwaters that are preferred venues for collection are also the universally selected brooding areas of gurviloos. Chactlalocs and their less common relatives like to burrow within log jam debris collected within these watery hollows.

Chactlalocs are mainly piscivores along the long Amazonian expanse they call home. Males may kill duckgong and aquatitan chicks during the brooding season for added protein, but the catfishes and characids make up the bulk of their diet otherwise.

REPTOMUSTELINAE (Colocolos "weasel-rats")[]

HE saw the extinction of a huge diversity of terrestrial predators due to the Pliocene Bolide Event, down towards small terrestrial crocodiles and caenolestid metatherians. Spec's necobaatarids seemed to have sailed largely unaffected through this event, especially the Reptomustelines. These are the most diverse of the necobaatarids, with some 25 species described throughout South America into Central America.

Why these sprawling predators hold their own against such parasagittal clades like the pusillonecatorids, zams or the chilla pokemurids is not fully understood. Suggestions such as their "inferior" retention of ankle spur venom as a novel defense do not hold merit. Indeed, colocolos are often heavily predated upon by their competitors, (quite successfully as an anecdotal observance). Perhaps their ability to enter torpor during times of prey decline might answer their success. Truth be known, like many other conundrums in Spec, this requires further study. Perhaps these sprawling "weasel-rats" have a reproductive or whatever else advantage not yet known.

Rainbow Tiger (Iritigridus insperatus)[]

This truly was an unexpected necobaatarid multi. The sight of a brilliantly hued mammal stalking stimpies and teddies alike in canopy rainforest startled researchers worldwide. Previously, it had been held that the unenlagaoid "pseudo-arbros" ruled this niche unchallenged as they were so common. However, the rainbow tiger is a crepuscular animal that flashes their brilliant coloration only during the dusk and dawn hours. This 5 kilo mammal is vulnerable to predation by large scowls and strigosaurs. Few recorded moments are known of this species. All are from spectacular hunts pursuing prey or remains recovered from an avisaur or strigosaur kill.

Ahpuks (Reptomustelus sp.)[]

The mortal terror of all creatures small, ahpuks tirelessly whip their way through grass and forb for the latest juicy micro-morsel. Ahpuks prey on a range of micro vertebrate and invertebrate animals. They will occasionally consume fruit when in season. They are preyed on in turn by scowls.

UNDESCRIBED SPECIES[]

These species are awating their taxonomic descriptions as well as a multitude of newly discovered multituberculates thanks to recent expeditions back to the world of Spec.

- Daniel Bensen, Morgan Churchill, David Marjanovic, and João Boto

Works Referenced: Toby White's, Multituberculate Notes