Ubiquitous to Spec's coasts and seas, the hesperornithines are the last of the basal Ornithuromorpha. "Hespies", as they are commonly called, were the first dinosaurs to successfully enter the marine niches in a big way. They are known from early Cretaceous deposits, some of the fossils indicating flightlessness having independently evolved several times. Having entered the seas for good, hespies seem to have only returned to land to breed and lay eggs.

HISTORY[]

On HE, hesperornithiformes died out along with all other birds outside of Neornithines. Spec of course, is different. These toothed birds continued into the Paleogene, albeit in reduced numbers. They disappear from the fossil record during the PETM; reappearing in the late Eocene in the form of Phocavis. This initial reappearance lead to a nearly worldwide distribution. The phocaviids even were found in the southern seas, traditional home of the penguins. They had a very long temporal range, the last members fading from the record in the mid Pliocene in southern Africa.

Phocaviids have only recently been studied in detail. The prompting came from a Paleocene bed of archaic hesperornithine oo-fossils, which contained large numbers of eggs laid in sand and overlain by repeated volcanic pyroclastic flows. The reason for such interest lays with the fact that modern hesperornithines are not known to lay eggs in beach sand, indeed they do not construct nests at all. For quite some time, it had been assumed that modern hesperornithines were directly descended from sea-going archaic Maastrichian/Paleocene ancestors.

BIOLOGY[]

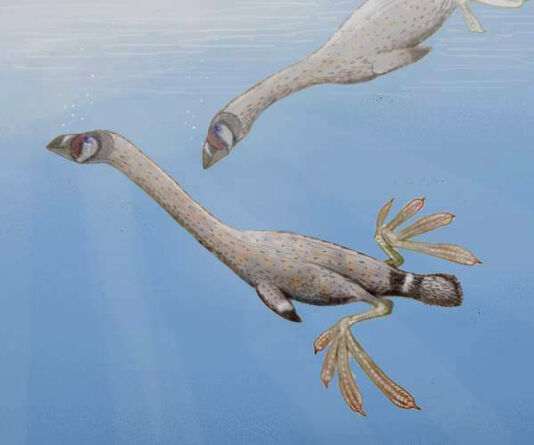

A hesperornithiform resembles nothing so much as a loon stretched and then flattened. These creatures lack the wings of their cousins, the ichthyornithiforms, and indeed, their foremost appendages have been reduced to jointless paddles. Seaguins' propulsive force is applied by the two hind legs, which are stoutly built, and end in enormous, lobed, feet.

The revised studies have shown marked contrasts. Modern hespies do belong to the order, but they are not closely related to any of the known archaic species. The phocaviids instead seem to have descended from flying members of the clade. Close study of phocaviids show primitive features in their wings, dentition and skeleton compared to archaic hesperornithines. However, the braincase shows massively advanced features such as development of the neocortex, further developments of the optic and auditory bulla which are completely unknown in archaic hesperornithines. This was a revelation, which is being further supported by fossils that are yet in press. The main guise of this interest was the difference between modern hespies and their archaic cousins with regards to reproduction.

Modern hespies do not lay eggs in sand and abandon their young, they don't even construct nests. These birds retain eggs within their bodies until they hatch. These archosaurs, like the qurry laurasiornithopods and heterodontosaurs; have found loopholes. Archosaurs and testudines (turtles) cannot retain eggs like many other sauropsids because of the unique properties of the egg shells. However, once the eggs are laid, they can be transferred into a pouch for safe keeping. The qurry ornithischians have independently developed throat brooding. The modern hesperornithines have developed cloacal pouches to hold their eggs in. These posterior pouches are richly developed with capillaries and frequently open their sphincter muscles to allow fresh oxygen to be exchanged. The result is that hespies mate out at sea, with the females beaching themselves once the egg or eggs are laid; pushing themselves across gravel, sand, rock or ice to incubate for up to three months.

MAREPSITTACINAE (Sea Parrots)[]

Both seaguins and penguins suddenly shoot up in size and diversity from the late Miocene onwards. It seems the more ancient phocaviids may have filled niches that the reigning warm-water mosarks, the later duckotters and abysmal walducks could not. Whatever the case, the phocaviids dwindled to obsolescence by the Ice Ages. Modern Hespies are quite common in the seas of the northern hemisphere, with a few species found south of the equator on tropical islands abutting cold upwelling abysmal waters in colonies shared with their penguin counterparts. One species is cosmopolitan. Sea parrots and seaguins rarely venture onto land, but are forced to make the excursion, periodically, to give birth. These birds are ovoviviparous, but their young are born still encased in the sack-like allentois, and would suffocate in an underwater birth. Thus, seaguin females must climb up onto the land, propelling themselves with sweeps of the feet and a snakelike wriggling of the body, lay their "egg" and then pull the chick free of the confining birth membrane. Further elaboration of this process varies from species to species.

Sea parrots are close relatives of the piscivorous seaguins, but they have specialized in mollusks for food. A sea parrot uses its robust beaks and large teeth to crack the hard shells of shellfishes and Arctic ammonites.

Also unlike the seaguins, sea parrots have retained the teeth in their upper jaw. Based on this character, sea parrots are believed to have diverged from the seaguins in the Eocene or early Miocene.

Common Sea Parrot (Marepsittacus pelagus)[]

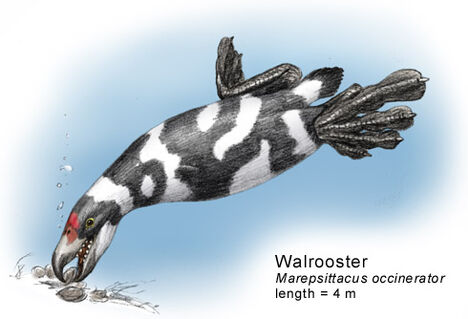

Walrooster (Marepsittacus occinerator)[]

These massive divers live in the Arctic seas, feeding mostly on bottom-dwelling mollusks such as shellfishes, which they detach from rocks using their hooked beaks, and crush the shells with their impressive battery of teeth. They also occasionally catch crabs, but hardly ever even try chasing ammonites like their smaller and swifter ancestors. There have also been reported cases of walroosters scavenging the carcasses of similar-sized creatures. It seems that with their powerful jaws and teeth they can crack the bones to get to the marrow, inaccessible to most other predators/scavengers.

Walroosters can often be seen in large numbers resting on Arctic rocky beaches or ice floats. The males have a very loud and recognizable voice, used during the mating season and related social disputes, which resembles the crowing of a cock.

Atlantic Sea Parrot (Maripsittacus atlanticus)[]

The Atlantic sea parrot is a generalist species. It is of average size for the clade, at around 2.5 meters and 200 kilos in weight. They may be found in a wide variety of near-shore environs from tidal flats digging in shallow mud, out to depths of 100 feet. Favored prey are clams between 200 grams to 1 gram in size and similar sized ammonites easily caught. A recent division has raised the closely related Bering sea parrot (Maripsittacus stelleri) to species status. Both species tend to have large rookeries of hundreds to thousands on offshore islands shared with jarrks and duckotters.

Knight Jar (Maricaprimulgus dracophagus)[]

Named with tongue-in-cheek for their feeding habits, knight jars are deep-diving seaguins who sweep huge numbers of immature sea dragonflies into their craws. Knight jars have a huge cosmopolitan range across the cooler to tropical waters of the northern hemisphere, including a large colony in the Galapagos. They are generalist predators of most sea dragonfly species, but will also take argonautoids and join baitball congregations if they come across them.

Knight jars are primarily nocturnal feeders, meeting the rise of sea dragonflies every night. These birds are also known for their grisly habit of snatching piranhakeets during their main feeding and breeding season - while the tiny penguins are busy devouring ample numbers of exhausted male baleen squids, the knight jars zip through their feeding frenzies. At nearly three meters in length and 300-400 kilos in weight, a single knight jar can take up to 10 pirhanakeets. These seaguins are lightning quick and can dive to depths far below their prey's reach within moments. Besides, the piranhakeets are too busy gorging themselves on cephalopod flesh.

Speckled Sea Jar (Sednaornis geladus)[]

The speckled sea jar lives permanently below ice in waters between 30 to 500 feet deep. This is the smallest of sea parrots, at less than a meter and 40 kilos. These birds have very thick, ragged bills to allow them to saw away at the thinnest spots of ice within their territories. They are much more generalist in their diets, taking winter slowed fish and ammonites under the ice as well as diving to depths of 500 feet to crunch shellfish. Their whisker-like bill feathers are exquisitely developed to allow them to sort out prey items.

These animals form snow caves for their two offspring. Like HE ringed seals, the female birds nestle for much of the 3 week incubation period; diving into the sea only if and when a polar drak bursts through. Several caves may be found throughout her territory. Still, up to 40% of the hatched chicks may fall prey to the draks, or to selkies when ice breakups occur.

CALCITRONINAE (Seaguins)[]

Using their feet as paddles, seaguins scull through the water in quick, jerking motions, mimicking the behavior of the squids and fishes that are their principle food. These birds retain teeth only in their lower jaws, and generally possess longer and more pointed beaks than their sea-parrot cousins.

The tyrant loons are a small tribe consisting of just two members. They have the unusual habit of beaching on ice floes or shallow sandbars when gravid. The young are hatched into open waters. Fish and ammonites are the primary prey of the lesser species; while the larger species seeks tetrapods. Both have short, broad beaks to allow them to crush prey with great force.

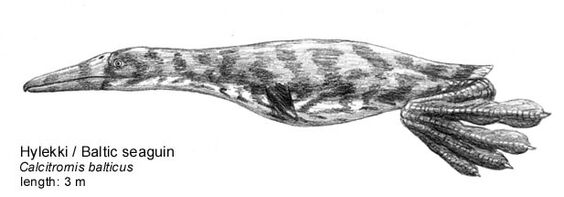

Hylekki/Baltic Seaguin (Calcitornis balticus)[]

The specific nomer is somewhat misleading, since these birds are also known from carcasses and flocks in Iceland and off the Baltic Sea. Unlike most true seaguins, hylekkis tend to nest in large rookeries alongside other sea critters like their maripsitticinine relatives and jarrk selkies.

This has been a boon, allowing spexplorers to see they have a polyandrous mating structure. Females have one to two tiercel; the males, who are around three quarter of the female's size, will hunt for her while she is gravid with up to 4 eggs. Surprisingly, the female seems not to make land-fall until well after egg laying. The chicks hatch within a week. The 300 kilo males heave ashore to their 400 kilo mate time after time for three weeks before the chicks scramble behind their mother into the surf. The whole family may remain near shore for another week before shooting out into the deep sea to parts still unknown.

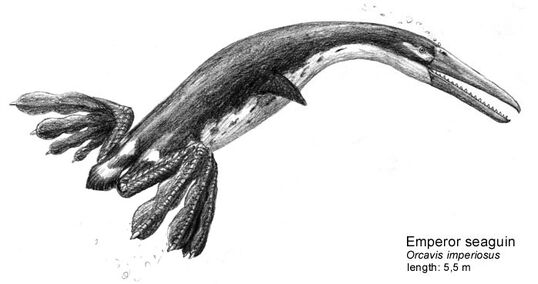

Emperor Seaguin (Orcavis imperiosus)[]

The 5 meter long emperor seaguin is the largest seaguin species. Though mainly a piscivore, it has been known to hunt the young of the smallest seaguin species.

Blueflank Seaguin (Orcavis velocinatans)[]

Blueflank seaguins are the most common seaguin species in the Arctic. Blueflanks are quite similar to their Cretaceous ancestors, and eat principally cephalopods (including larval baleen-squids). Nearly half of its length (of 2.5 meters) is head and neck.

Blue Tyrant Loon (Orcavis velocinatans)[]

The blue tyrant loon is a common Arctic hespie. These generalist feeders mostly take fish and ammonites, but will also snap up the young of mammals and birds alike. At 2.5 meters and some 300 kilos, they are too small to threaten the majority of adult marine mammals and birds.

Blue tyrant loons are easily recognized by their stout bills and dappled coloration. The flanks flash vividly blue when caught by the pale summer light; the rest of the bird is a mottled white and dun blue coloration. This serves them well in all seasons. The blue tyrant loon remains quite close to the ice in all seasons; females haul out for the incubation period while males hunt for food. Leads in the ice are sensed with their delicate hearing, allowing them to penetrate far north during especially warm years.

Polar draks are their principle predators. Nesting females live in matrilineal families that offer good protection. Even a starved drak will turn back at crushing tooth-lined jaws. However, when leads close and trap flocks; they hope against hope that a polar drak will not discover their breathing hole or several of them may end up dragged up onto the ice with their throats torn out.

Like many other Spec marine denizens, blue tyrant loons may be found in Spec's St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario. There they feed on warm blooded prey such as selters and walrooster chicks.

Empress Seaguin (Orcavis regina)[]

The empress seaguin is the terror of the cold northern oceans. Murders of these birds have been known to tear apart kronosharks and chilled giant mosarks with impunity. At some seven meters and close to 4,000 kilos, they are the lords of the bitter frigid seas. They can be found across the cooler waters of the northern Atlantic and Pacific into the Artic. An Empress raising her unmistakable head above waters near a rookery provokes an instant reaction - that reaction may be a quick head raising or an all-out race to higher beach. These birds are totally in control of their realm...and they seem to enjoy it.

Empress seaguins live in life-long monogamous pairs within matrilineal rookery flocks. They prey on all life in the sea, but prefer warm-blooded animals. All their cousins are torn apart, as well as all unlucky mammals who stray into their jaws. Only the presence of giant mosarks in the tropics prevents them from taking over the oceans of the world.

During the breeding season, the murders find safe havens on sandbars in estuaries near large rookeries of their prey. The females lug their huge mass half ashore; digging out enough sand so their chests float easily in water while their hind ends remain beached. No known terrestrial predator has ever threatened these birds and lived to tell of it. One one notable occasion, a spexplorer reported seeing a saber tyrant being dragged to its death by two sister empress, after which the whole flock ripped it apart and feasted. The eggs seemed not to suffer since the females were soon back ashore; stuffed by their mates with tyrannosaur flesh.

Empress seaguins have short, broad mouths much like their smaller kin. They also possess a hooked beak and a scooping bill like any raptor. Acting in concert, the tearing tip works with the shredding posterior teeth to yank away huge chunks of flesh. They do not roll like crocodiles to secure meat; instead, they hone keratin and tooth against gravel, driftwood and bone to razor sharpness.

Tuna Bird (Delphigavus thunnoides)[]

The tuna bird is probably the fastest of the hespies. Top speeds of 70 kph have been reliably recorded. They literally rocket out of the surface to heights of 20 feet in the pursuit of their main prey, bait fish and squid. These enigmatic north Pacific birds are little known. They seem to travel along the Pacific Gyre from warmer waters to the south up to the frigid Bering seas. Only one small rookery has ever been discovered in the Priblof islands. It seems that a single male mates with several females and has no further care for the offspring.

PACTIROSTRAVIDAE (Archers)[]

Unquestionably the strangest of the hesperornithiforms, the archers are famous for their possession of what the rest of their family lacks; archers have wings.

Since the discovery of the first hesperornithiforms as fossils, paleontologists assumed the flightless clade to be entirely wingless, its species specialized for their marine existence at the expense of their wings. Then, early in the 21st century, winged, loon-like hesperonithiform fossils such as Potamornis began to come to light as winged hesperornithiforms - but still flightless.

The pectirostravids are clearly descendants of those long-extinct birds, but the past 66 million years have seen some changes to the taxon, mostly concerned with the birds' shift from fish to plankton as their principal food source. Like flamingoes, archers sift their food from the water, using long bow-shaped bills lined with a net of tiny teeth.

Indian Arjun (Pectirostavis arjunai)[]

Despite its name, the Indian arjun may be found all across western Africa, the Middle East, south and southeastern Asia, traveling in huge flocks to feast upon the tiny denizens of the rich coastline of the Indian Ocean.

Like flamingos, the archers' closest Home-Earth analogues, arjuns are colored bright pink by the plankton they ingest, but unlike our familiar long-legged waders, the pectirostravids are descended from paddling fowl, and have short, relatively stubby legs. Rather than walk through mudflats, these duck-sized birds swim over the surface of the water, skimming their long, curved beaks through shoals of microscopic prey.

Like most other archers, arjuns are gregarious, often congregating into flocks of several thousand members during their seasonal migrations, then splitting into smaller flocks of a few hundred individuals upon coming to ground. Each sub-flock will stake out its own patch of sea-water to "graze", methodically sifting it for organic material before taking off again.

DAGONAVINI[]

When spexplorers first arrived, they were divvied up into dozens of teams. One team doing paleontological work in some New Jersey late Pliocene shore beds recovered the enormous skull of a seaguin. Naming it after HE's sperm whale Physter macrodon, the 2.5 meter skull was stored away and spoken of mainly in academic and Spec fan circles. Impressive, but regarded much like HE's Andrewsarchus or Daeodon, an after thought monster of a close, but still bygone era.

But a young mammalogist affectionately known as Coyote was diving off of Bermuda studying and filming an adolescent male striped walduck recently kicked out of his pod. He was preparing to tag the animal when a massive thing rose up from the dark depths and slammed its 3 meter golden jaws around the hapless monotreme. Blood spattered and bloomed like squid ink. The poor man was less than two feet away from the pitiless eye of the monster.

Coyote was raised shaking from the sea. All that could be heard from him was, "Dagon, Dagon!!!!". Eventually he recovered, but the nomer stuck unofficially. Luckily, he had tagged the sea monster with the camera. This allowed more sane members of the expedition to observe the creature over several days. This results were surprising. This animal was a hespie; the largest ever known. They watched the female return to a shallow Bermuda island cove where she remained for the following days. The film tag frustratingly showed her hatching a chick before it went dead. The location was tracked, divers later recovered several eggshells; partially reconstructed, they showed an egg larger by far than any other tetrapod known in either timeline.

By this time Coyote had recovered and named the species Dagonavis, he spend the next few years searching for these mysterious birds and following their living patterns. It turned out that dagons were deep divers, hunting at depths of more than half a mile. Tagging and filming as well as dissection of beached specimens in Iceland showed a preference for cephalopods and fish, with some sharks and walducks occasionally present.

The modern seaguin tribe was christened after this monster; however, in one of those ironies, it turned out that the Pliocene Physteravis was close enough to the dagon to be regarded as an extinct representative of the genus. The dagon, also known as the ambergran, was rechristened Physteravis marovum.

Ambergran/Dagon (Physteravis marovum)[]

The ambergran must be the most magnificent of the already great hesperornithine clade.

Females reach over twelve meters and males are little smaller at nine to ten meters. The big females weigh up to 12,000 kilos lean and may be close to 16,000 kilos during the breeding season. Unlike all other hespies and indeed unlike all other archosaurs, the female ambergran remains out at sea for the duration of her pregnancy. Still, when the huge females cloak their eggs, they can no longer dive to great depths. Their ravening hunger turns to the supine prey close to the surface. Any reptile, mammal, or cephalopod unlucky enough to catch this hungry mother's eye or alert her ear will be seized and torn apart.

The one or rarely two eggs are incubated for three months; the mother burping them every few minutes. When the eggs are hatching, the mother will often gently roll the egg in her mouth to crack it, much as some crocodilians and qurry ornithischians will do for their young.

Even though ambergran eggs are enormous, the hatchlings are still only 10 kilos in size. They are kept well protected by their mother within her jaws in bays and estuaries while their father hunts for both of them. Growth is rapid. The chicks put on hundreds of kilos within months. Their first year may see them nearly 1,200 kilos in weight. Both parents will take the chicks with them out into the open sea after eight months to join the larger flock.

The chicks will remain with their parents for nearly three years; helping with the next hatchling before reaching their adolescent weight of 5,000 kilos and joining their relatives out in the open sea. It will be another 5 years before they consider raising their own chicks.

Ambergrans are the only cosmopolitan member of the hespies. They are found in all seas, but prefer the cooler latitudes, mostly heading into the tropics only when certain deep-sea prey are massed for breeding. Their own breeding can be varied, but is primarily limited to cooler waters, where giant mosarks cannot go.

The latter nomer, ambergran, comes from regurgitated pellets. Ambergrans eat large quantities of deep sea prey, many of while have bones or keratins than cannot be digested. This grain-like oily mush is much like the regurgitations of HE sperm whales and giant diving mosarks in its pungent odor. The musky vomit is being studied with great interest as a possible perfume base.