Aside from dinosaurs, the only other archosaurs to make their home on the present-day Specworld are the crocodiles. These semi-sprawling, cold-blooded archosaurs first appear in the Triassic, emerging, together with dinosaurs and several other groups, from the chaos that marked the end of the Permian. Since then, crocodiles have experimented with a number of lifestyles, from terrestrial ambusher and herbivore to marine shark- or mosark-like predators, but their favorite niches have historically been those of semiaquatic ambush predators. Today, most crocodylians conform to this lifestyle, and are little different from their counterparts in our timeline, but others do not.

NEOSUCHIA[]

Despite its name ("new crocodiles"), this clade is almost as old as the entirety of crocodiles, reaching back to the Early Jurassic. Neosuchia includes Eusuchia, the only clade of crocodiles that survives on Home-Earth, as well as the ancient but unremarkable goniopholidids.

DYROSAURIA[]

Dyrosaurs are the last lineage of a group of crocodylians known as tethysuchians, that also included other longirostrine forms such as the spectacular Sarcosuchus, of which they were the last representatives in the post-CTM Cretaceous. They expanded into marine niches, colonising both sides of the Atlantic and the warm Tethys Seaway, diversifying into a variety of aquatic predators, from the familiar long-snouted gharial like forms to shorter-snouted turtle specialists to possible macropredators. This continued into the Eocene in both timelines: they weren't the least bit impaired by the KT event in HE, and in neither timeline did the PETM affect them. However, a crucial change happened between both timelines: in HE's Eocene, dyrosaurs declined and became extinct, while in Spec they didn't. Many proposals have been suggested, from the smaller impact of the Azolla Event to possible roles played by early whales in dyrosaur extinction.

Whatever the reason, dyrosaurs remained fairly low key during the Oligocene, but had a worldwide distribution in the Miocene, much like gharials did in HE’s Miocene. The Pliocene eventually posed a fatal blow, destroying most of their diversity, but about 4 species remain, most of them being island endemics. Rather gharial-like animals, they are nonetheless even more aquatically adapted, being the crocodylians most suited to live underwater, easily being distinguished from true gharials by their eyes, which are positioned frontally and not upwards just like in choristoderes. Modern species also lack gharas, relying entirely on infrasounds to communicate, though distant extinct cousins like Sarcosuchus did have a similar structure, and are the crocodylians with the smallest amount of scutes and most webbed feet.

Makara (Theosuchus gangetica)[]

The Indus, Ganges, Irrawady and Brahmaputra river systems are home to the largest living dyrosaurid, the 7 meter long Makara. Unlike HE's gharial, the Makara has a thicker, wider snout, remaniscient of *Tomistoma*, and thus it is not limited to simply fish: it is the apex predator of it's habitat, capable of dealing with champsosaurs, the Varuna, occasional mosarks and land animals such as dinosaurs. Nonetheless, most of it's diet is composed of lungfish and coelacanths, wrestling the sarcopterygians, which can grow to comparable sizes in these waters. Like all dyrosaurids, the Makara is a rather cryptic animal, spending most of it's time hidden beneath the surface, only occasionally dragging itself to shore to bask. The only time these animals are witnessed very frequently is the mating season, when females drag themselves ashore to compete for the best nesting spots. The young pretty much fend for themselves, crawling out of their nests and arriving en masse to the water like young sea turtles.

Namaka (Geolurhamphus namaka)[]

In it's supreme isolation, Hawaii is probably the last place a crocodilian would be expected to appear in. Yet, somewhere in the late Miocene, dyrosaurids managed to reach these remote islands, probably dragged by unusual sea currents. The Namaka occurs over most of the archipelago, it's range mostly focused on the central islands of Kauai, Oahu, Molokai and Maui, but also present on the northern and eastern shores of Hawaii proper and on the smaller islands to the northeast. At 3 meters long, it's a rather small dyrosaurid, preferring mostly sheltered bays and lakes, though more than capable of surviving on the beach.

Like many distant oceanic islands, however, Hawaii is poor in freshwater fish, so even bay dwelling animals frequently forage out at sea, hunting in the rich coral reefs. The female lays about four eggs per clutch, the smallest clutches of all crocodylians, which compensate in size, being proportionally twice the size of the makara's.

Daucina (Geolurhamphus daucina)[]

A similar species to the Namaka occurs in the islands of Melanesia. The Daucina is very similar to it's Hawaiian cousin, though slightly larger, darker in colour and laying larger egg clutches. It also lives almost exclusively at sea, being the most pelagic living crocodylians, hunting for pelagic fish and squid often miles from the shoreline, though it still returns to the beaches to lay eggs, which occurs year round. It co-exists in some areas with it's relative, the Apam (see below), which it avoids competition with due to the latter’s preference for coastal and freshwater biomes. Juvenile Daucina are still mostly coastal animals, however, and not only compete with the Apam, they are also frequently it's prey. Nonetheless, the Daucina's grasp is strong enough to severaly restrict the Apam's range, as it has not yet gone south of the Solomon.

Apam (Serapisuchus porosus)[]

The Apam is basically Spec's answer to HE's Saltwater Crocodiles: the most successful living dyrosaurid, it ranges across all of Southeast Asia, the Solomon Islands, northern Australia, and even eastwards, with a population in the Seychelles that occasionally occur as vagrants in Africa and Madagascar. Unlike it's HE analogue, however, the Apam is perfectly comfortable in living a more marine existence, though it still prefers freshwater habitats, often being found miles inland. Apparently having evolved in Sulawesi, it's recent success appears to coincide with the Pliocene/Pleistocene decline of it's relatives, simply filling empty niches.

EUSUCHIA[]

Many of Spec's crocodylians are indistinguishable from their Home-Earth counterparts. Spec's bayous are home to Mississippi alligators (P-Alligator paramississippiensis), and its Nile is patrolled by Nile crocodiles (P-Crocodylus niloticus); they differ from their mirror species only by reaching large sizes more commonly, due to the abundance of large prey.

GAVIALIDAE[]

The famous slender-snouted crocodylians, gharials had a wide range since the Maastrichtian, with the marine North American Eothoracosaurus occuring in the Ripley Formation, alongside mosasaurs. Spec retains a larger variety of gavialids than HE, which is rather ironic given that in the latter their competitors such as dyrosaurids became extinct.

EOGAVIALINAE[]

An African-based clade, eogavialines disappeared in HE's Pliocene, but strangely they are still alive in Spec. The absence of Mecistops and other similar longirostrine crocodylians from Spec seems to be a key factor, allowing these crocodylians to remain somewhat more diverse, enough to remain in less vulnerable niches.

Balearic Gharial (Pseudomecistops mediterranea)[]

With an average size beneath 2 meters, this is a rather small crocodilian, apropriate for its rather reduced range, the Balearic Islands. How the gharial's ancestors arrived to these islands is unknown - presumed to be from a now defunct north African radiation of the genus - though it coincides with the local disappearance of the Iberian Lotan. The Balearic Gharial is almost exclusively a beach dwelling animal, given the rarity of rivers and lakes in these islands, diving in the sea to ambush prey hidden amidst the Mediterranean seagrass prairies. During the mating season, males display on land, using the ghara to making strange noises, although mating itself still occurs in the water, as in most neosuchians. The young form creches on tidal pools, feeding on animals stuck there. A small, poorly studied population also occurs in Jucar’s estuary, seemingly having arrived there recently.

Congo Gharial (Neogavialis congoensis)[]

The Congo is home to one of Spec's largest crocodylians. At a whooping 12 meters, the Congo Gharial is one of Central Africa's many strange giants, and one of it's river's largest inhabitants. A rather shy animal, it can nonetheless be easily spotted, spending most of its time floating in the water surface. Almost exclusively feeding on small fish and crustaceans, it transformed the usual gharial fast motion capture into a form of facultative filter feeding, trapping prey as it moves it's jaws along a shoal rapidly. With adults surrounding the vulnerable young, the Congo Gharial has very little natural predators.

GRYPOSUCHINAE[]

South America was home to a range of gharials since the Eocene, which dominated its waterways alongside champsosaurs so effectively that other crocodilians were mostly either conservative generalists or very specialised. During the Miocene some extended into marine niches, though they remained mostly around South America's shorelines. Currently, two species remain, both belonging to the genus Ikanogavialis.

Orinoco Gharial (Ikanogavialis intermedius)[]

A rare old South American river endemic not from the Amazon (though reports do indicate a similar animal may live there), the Orinoco Gharial reaches a length of 7 meters or more, being South America's largest crocodylian. The Orinoco Gharial feeds primarily on the various types of fish and crustaceans endemic to the Orinoco, but it is large enough to pose a threat to even small crocodilians. The male has a rather colourful ghara, with a bright orange hue, though it's not clear if the colour plays a lot of importance in sexual selection.

Murua Gharial (Ikanogavialis papuensis)[]

One of the biggest mysteries in both timelines is the presence of a distinctively South American gharial in the Solomon Islands. A currently unknown Pacific radiation is the best option, though with animals like iguanas in the Fiji, simply a lucky sea travel would have sufficed. Whatever the reason, the Murua Gharial is a very relevant gift Spec has given to zoology, as it allows us to understand how its now defunct HE analogue lived. This gharial is mostly a coastal animal, but it can also be found in it's mangrove swamps and rivers, preferring large bays and shallow atoll pools as its favourite habitat. It feeds on a variety of fish, mostly marine, that it captures in the typical gavialid fast motion, usually by striking from the bottom. Amazingly enough, it manages to co-exist with not one, but two types of dyrosaurids, a niche partitioning thought to be similar to that of the extinct HE Murua Gharial with saltwater crocodiles, the former selecting smaller prey than the latter.

BOREALOSUCHIDAE[]

Also known as "false-crocodiles", borealosuchids are a lineage of very crocodile-like eusuchians that date as far back as the Late Cretaceous with forms like Borealosuchus. They are instead most closely related to gharials, and some authors even move them to Gavialoidea. Regardless, the fortunes of these animals seem defenitely to be better in Spec than in HE, having outlived their relatives for 30 million years or more. About 6 species exist distributed across not only the Americas, but also Asia.

ALLIGATOROIDEA[]

This was mainly a Laurasian clade, well known from diverse Cretaceous and early Cenozoic forms like Acynodon and Albertochampsa, as well as the iconic Deinosuchus, though on both timelines South America became a haven for these animals while most of Laurasia eventually lost them. These crocodilians can be distinguished from other eusuchians by their short, broad and often flat muzzles, and the fourth tooth fits in a depression in the upper jaw. They are less tolerant to salt water than their relatives because their salt glands are usually vestigial, but they are also more cold tolerant, and they can be found as north as southern North America and as south as La Plata. Alligatoroids are odd amidst eusuchians for their more omnivorous habits, particularly pronounced in Spec, where herbivores, while not common, have still occurred several times.

Beartrap (Captionasuchus captionasuchus)[]

The wetlands of Spec's southern North America are home to one of the strangest crocodylians in Spec. The beartrap displays exactly that: its jaws have become extremely wide, and display quite large, menacing front teeth. It lays immobile in the swamp substrates and shorelines, concealing its body carefully. Once a prey animal passes by, it quickly traps it with its teeth. Often times, beartraps actually just snap off limbs, though if the prey dies of blood loss nearby, it will move to take it. Rather stationary animals, they do move long distances at nighttime, searching for new hunting grounds or mates.

Relationships of the beartrap with other alligatoroids are uncertain, though it is usually agreed they diverged from an animal akin to Brachychampsa, based on characteristics of the dentary absent in other alligatoroids.

ALLIGATORINAE[]

More common on Spec than on HE, there are at least five living species distributed across Laurasia.

Ryu (Melanoalligator nipponicus)[]

Endemic to Kyushu, Shikoku and Honshu's subtropical and warm temperate habitats (with occasional reports from northern areas; see below), this alligator has been regarded as the most basal of it's genus, though unambiguous fossils are only known as early as 550,000 years ago. It is notorious among alligators for its terrestrial habits: while it spends quite some time in well sheltered pools and lakes, it can also be easily found on the forest floor, ambushing prey or eating fallen fruits. It is among Japan's apex predators, and as an adult it has little to fear and preys on anything from small mammals and birds to the native spelks.

A quite solitary animal, it only meets other members of its species during the mating season, usually by walking at random for miles with nothing but the male's infrasounds (and perhaps the female's pheromones) as a guide. The coitus takes place in the water like in most neosuchians, since they are less vulnerable there and because lubrification problems are solved. After several weeks, the female will build a nest of rooting vegetation in her territory. Like in most crocodilians the mother will protect her eggs from hungry mammals and maniraptors, but she only briefly takes care of the babies, which are on their own after roughly a week, when they leave. Baby Ryus that survive predators and find a pool stay together until they are too big to share the same territory, resulting in only one juvenile staying and the others going away to find a new home again. Most die due to cannibalism by older Ryus, and thus probably only one member of the original 20 egg clutch will remain to the end. Or none at all.

Alligatorids are indeed well known for their higher tolerance to colder temperatures than other crocodilians, but Ryus might be the crocodilians with the highest capacity of living in the cold. Sightings of Ryus occur all over Japan, and a few even occured in southern Hokkaido during the summer, though obviously this is very rare. Like other cold living alligatorids these cryptic populations likely hibernate during the winter, and its needless to say most of these animals are huge, supposedly reaching the limits of the species' size.

Sumerian Alligator (Truncachampsa palustris)[]

In spite of the name, the Sumerian Alligator is not restricted to Sumeria, being found in rivers, marshes and lakes across most of the Levant and India. Having an average size of 3.7 meters, these animals are opportunistic hunters, but specialised somewhat in a diet of turtles, crustaceans and shellfish, avoiding competition with other local crocodylians.

CAIMANINAE[]

By far the most common living clade of alligatoroids in both timelines, caimans are mostly restricted to South America, where they occupy the average crocodylian niche. Most caiman diversity is very similar, with p-Palaeosuchus, p-Caiman and p-Melanosuchus being present. However, there is one important distinction: In Spec, alligatoroid omnivory took it's logical extreme in one particular lineage. As a result of their more vegetarian diet, caimaguanas have larger and more complex guts, on which they store digested vegetation and obtain as much nutrients as possible thanks to specialised stomacal flora and vermentation; the gastroliths consumed for boyancy issues also come in handy to help smash their food. Having relatively small, leaf like teeth, this bizarre turn in alligatoroid evolution seems to have been a Miocene product, for reasons so far poorly understood.

Green Caimaguana (Iguanocaiman brasiliensis)[]

The most common member of the genus, its range extends from the Llanos to Pantanal and from the easternmost coast of Brazil to the Andes, whereas most of its relatives have more restricted ranges. A regular sized caiman, it reaches a body length of 2 meters, and it is fairly adaptable, being able of both living in zones affected by large floods and ones that are dry for several months, and if necessary it can either spend months on land or in the water.Vulnerable to jagulars, sebecosuchians and errotyrants on land and to crocodiles, carnivorous caimans and selters on the water, the caimaguanas have ventral scutes, much like HE's Chinese Alligator. They can also easily be told apart from other caimans by the larger and more round body, whose shape is derived from the extensive and complex guts. Caimaguanas usually can be found in a same population concentration ratio as in most caimans, but in the breeding season they gather in massive groups and head to specific egg laying locations like riverbanks or freshwater islands. Like in HE iguanas and turtles the animals borrow their eggs on the riverine sands, and abandon them, leaving the young to fend for themselves. The mortality rate of the young is very large, and only one or two out of a whole clutch of up to 30 will survive to reach adulthood. As soon as they born they go after invertebrates, and only afterwards they began feeding on aquatic vegetation like adults; the transition between the diets is helped by consuming the adults' faeces, acquiring very important bacterial flora.

Managator (Iguanocaiman giganteus)[]

The largest member of the genus is found on a range that extends from Pantanal to La Plata. With a length of 6 meters, the Managator is among the biggest known caimaguanas, and very large by alligatorid standards. Dark in colour, it can be at first mistaken for some very large alligator, but a closer inspection reveals the different jaw and teeth morphology. Unlike most caimaguanas the Managators protect their nests, but the young are left to fend for themselves.

Cuban Brown Caimaguana (Iguanocaiman cubensis)[]

The islands of the Caribean are inhabited by several alligatorids that crossed the sea multiple times across the late Cenozoic. Among them is are some species of caimaguana, which adopted a more terrestrial lifestyle. The tail, for example, is now less deep less deep, since the chances of using it for swimming are minimal now. This particular 3 meter long animal share the island of Cuba with the smaller Black Caimaguana (*I. nekosirtes*), which also occurs in Haiti. These two forms seemingly are not particularly closely related, the Cuban Brown Caimaguana seemingly being derived from an earlier migration, and indeed it bears some slight refinements to a terrestrial lifestyle, like hoof-like nails, that it's relative lacks.

GONIOPHOLIDIDAE[]

Laymen can hardly tell these crocodiles, which have stayed almost unchanged since the Early Jurassic, apart from eusuchians – except by one feature: Cuttercrocs have smooth, sharp edges on their teeth which are a formidable tool for cutting meat. Consequently, they eat more terrestrial prey and less fish than their eusuchian relatives, and their attacks are quite a bit more bloody. Like eusuchians, however, cuttercrocs ambush their prey in water.

ZIPHOSUCHIA[]

This group, extinct in our timeline since the Miocene or so when the last South American sebecosuchids died out, was – and, in Spec, is – the most diverse group of terrestrial crocodiles. Astoundingly, Ziphosuchia includes carnivorous as well as herbivorous forms.

In Spec, three ziphosuchian clades have survived: the bone-cracking crunchercrocs of sub-Saharan Africa [or all warm parts of the Old World?], the herbivorous hoplocrocs of Madagascar and Africa, and the ferocious, theropod-toothed baurusuchids of Madagascar.

LIBYCOSUCHIDAE (Crunchercrocs & Weaselcrocs)[]

Crunchercrocs are peculiar creatures, the crocodylian answer to the mammalian hyenas of our timeline. Never longer than 2.5 m from snout tip to tail tip, crunchercrocs spend most of their time lying in high grass or under trees and trusting their formidable armour. When they become hungry, however, they stand up on their surprisingly long legs and head off to wherever their meanwhile proverbial sense of smell leads them. (The smaller species even sometimes climb trees to smell farther.) That place can be anywhere – different crunchercroc species roam semideserts, savannas, dry forests and rainforests in Africa and southern Asia –, and anything that moves and isn't too big, but most often, it is the fresh remains of a priscataur kill.

With their strong, rounded snouts, weak jaw muscles, and relatively small, sharp, bladelike teeth, moloks, pantherbulls and black beasts are very well equipped to kill prey by running into it and taking bites out of it, but they are understandably bad at cleaning, let alone eating bones. This is where the crunchercrocs come in. With their immensely strong jaws, which are lined with many small, low-crowned, conical, broad-based teeth, 20 crunchercrocs can let the remains of a grassbag carcass disappear with no trace in 3 days.

The oldest known crunchercroc is †Libycosuchus brevirostris from the middle Cretaceous of western Africa. It is only known from a skull that already shows most of the adaptations that characterize today's crunchercrocs. The biggest species is Crococrocuta invincibilis, which lives in the Serengeti.

Crunchercroc (Crococrocuta invincibilis)[]

One of the largest living libycosuchids, the crunchercroc is a generally 3 meter long critter endemic to the vast savannah and scrub landscapes of Africa, the Levant and India. A formidable carnivore in a land where abelisaurs thrive, it's formidable jaws and honey-badger levels of aggression keep most competitors away, not even needing an extensive armour. In fact, it frequently follows the dinosaurs, often harassing them out of their kills, though usually it doesn't need to: most dinosaurs cannot deal with bones, let alone abelisaurs with their weak jaw muscles, short snouts and small teeth.

Therefore, a lot is left in a carcass, even those consumed by dromaeosaurids, and thus the crunchercroc, with it's powerful jaw muscles and crushing molars, can gorge itself without even driving predators off their kills. Within a few days, even titanosaur corpses are gone as crunchercrocs gather. It has been speculated that it is the crunchercroc and its relatives, rather than abelisaurs, that keep large tyrannosaurs from moving south, being less capable of a more scavenging existence with these notosuchians around.

Of course, the crunchercroc is not just a scavenger, as flightless predators can't cover enough distances to live solely off others' kills, and it feeds on a variety of prey, from turtles to saurolopes to xenotheres, as well as occasionally on berries and fruit. The crunchercroc is cathemeral, though usually preffering to hunt at night. Crocodylomorphs in general have a formidable sense of smell, and the crunchercroc has one particularly refined olphaction, being capable of detecting prey from miles away. Unlike neosuchians, notosuchians retained vomeronasal organs, and in the crunchercroc the Jacobson's organ is very large and takes a role in detecting prey scents.

Foraging usually alone or in pairs, the crunchercroc has nonetheless a very complex social interaction system. Nomadic, crunchercrocs leave odoriferous messages to other crunchercrocs by secreting a sticky liquid from their cloacal glands, left on grass or other easily accessible places. By smelling these markings, crunchercrocs can determine how healthy or sexually available other crunchercrocs are, much like with mammals, and may pursue or avoid other individuals accordingly. Mating is a complicated affair, as females have a muscular seal that makes forced intercourse impossible, so a potential mate spends several days or even weeks sucking up to her, lowering the head in submission, emitting guttural sounds akin to those of baby crocodilians, and bringing prey. After mating, the female borrows a hole or steals one from another animal and lays the eggs there, leaving them in care of the male, whose metabolism slows down as he remains vigilant near the eggs. After incubation's over, the female takes over and runs the male out of the hole, the young following her around for over half an year.

Rock Weaselcroc (Eupolydaedalus albigularis)[]

"Weaselcroc" is a designation given to African non-crunchercroc libycosuchids, though sometimes used as the common designation for the clade. The rock weaselcroc is a common denizen in sub-Saharan Africa, reaching a maximum size of 2 meters. Foraging on the ground, it hunts primarily small mammals and feathered dinosaurs such as ground birds and oviraptors, as well as on a variety of lizards and insects. It sometimes also climbs trees, mostly to attack beehives, but like most weaselcrocs it is less adapted to climbing than crocvars, with a less developed sense of balance. Largely diurnal, it spends the night in holes in the ground or in hollow tree trunks, often accompanied by other weaselcrocs. At nighttime, any aggressive disputes seem to be put to rest, the animals engaging in affectionate behavior like licking and grooming.

Thicket Weaselcroc (Aurevoay purpurea)[]

Madagascar has an unique endemic radiation of libycosuchids that only recently has begun to be understood. Having arrived somewhere in the Pliocene, the Malagasy weaselcrocs are represented by about six species distributed across the island and the nearby Comoros. Ranging across the thicket-dominated semidesert in the south of the island, the thicket weaselcroc is a mostly nocturnal insectivore, feeding primarily on termites, and thus having less developed molars than its relatives. It can be found in family troupes, wandering across the semidesert. With black stripes in it's otherwise gold tail, the thicket wesealcroc is speculated to reflect ultra-violet light from these dark scales, using it as a form of signalling similar to North American streks and multies.

HOPLOSUCHIA[]

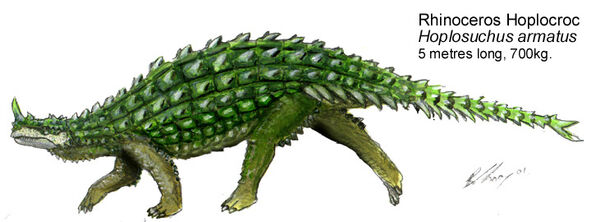

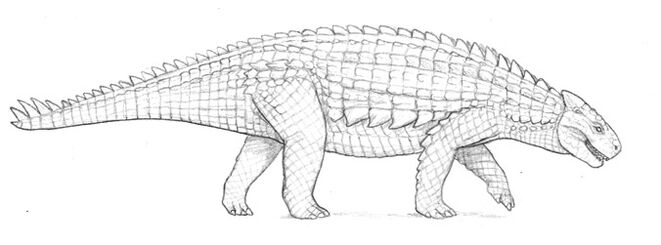

Hoplosuchians are bizarre terrestrial herbivorous crocodilians of Africa and Madagascar. Their low, armoured body form mirrors that of their distant cousins, the long-extinct aetosaurs of Triassic times, as well as that of the dinosaurian ankylosaurs and vanguards. Their skulls are short, solidly built affairs with broad snouts and closely packed leaf-shaped teeth. All species have an extensive coat of spiny osteoderms protecting their dorsal and ventral surfaces.

Although their Palaeogene fossil record is unknown, the hoplocrocs' ancestor was probably one of the small herbivorous crocodilians (e. g. †Simosuchus clarki) that were widely distributed in Cretaceous Gondwana. The high diversity of hoplocrocs on Madagascar, including the presence of many primitive species, suggests that the group originated on that island and later colonized the African continent by rafting or swimming.

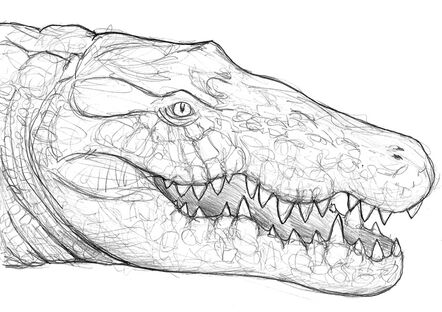

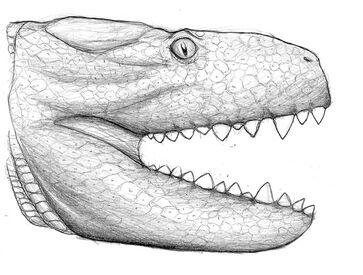

Rhinoceros hoplocroc (Hoplosuchus armatus)[]

The rhinoceros hoplocroc is a large, conspicuous herbivore that lives in open woodland and savanna. It feeds on leaves and tender shoots, digging for roots and tubers during the drier parts of the year. These creatures are solitary, using their long horn in jousts over territory and mating rights. Interestingly, the eggs are laid and buried in a simple pit dug in the ground. The adults provide no parental care and the hatchlings are left to fend for themselves. This is quite unusual among crocodiles.

Gargant (Gargantuis crassus)[]

The gargant (which can weigh up to 1.2 metric tons) is the largest of the hoplocrocs. The most massive animals on Madagascar, adult gargants have little need for their armour as protection. Instead, some suspect, their chain-mail of bony scutes functions rather like a girdle, keeping these herbivores' massive digestion system of from splitting their bellies open at the seams.

Adult gargants have no natural predators, but as young, they are preyed upon by the larger species of croclion and by rukhs, which swoop down upon gargant herds to seize their young.

Aardcroc (Afrosuchus terrestris)[]

The African hoplocrocs are small and not particularly diverse. These species are small, and their armour plating tends to be more extensive than that of their cousins in Madagascar.

The aardcroc is a meter-long herbivore of south Africa's savannas. These creatures eat a wide variety of plant material, including herbs, grass roots, and tubers, and make their homes in burrows on the banks of rivers.

In the heat of the dry season, aardcrocs enter these mud burrows and enter a period of extended aestivation, lowering their metabolisms drastically to conserve precious water. Predators like mattiraptors and archaeoplumes have been known to search for these burrows and devour their occupants.

Painted Thresher (Afrosuchus spinifer)

[]

A cryptic and poorly-studied creature of the deep jungle, the painted thresher is probably related to the more widespread aardcroc. The painted thresher's habits are unknown, but judging by its compact build and upturned snout, it probably lives like a pig, rooting through forest detritus.

Pincushion Hoplocroc (Angilasuchus polyspinus)[]

A recently discovered hoplosuchid from Madagascar's northeastern forests, the pincushion hoplocroc has taken its family's thorny armor to the extreme. The creature's backside is almost entirely covered with thorns, from its nasal horn to the end of its mace-like tail. The extensive defense ensures that most predators (even croctigers) give wide berth. When mating season arrives, males (distinguished by their `crown of thorns') attract females with shows of strength and advertising their presence with loud honking noises. Once a male has attracted a mate, the male must carefully position himself on the female.

Mome-croc (Suinosuchus chloris)[]

One beast that is almost constantly seen in the periphery between the forest and the wabe is the mome-croc, a large croc roaming the forest floor seems a long way from home. A pig-sized, destructive hoplocroc, very round and quite heavily built for its size, it has an upturned, horny nosepiece used like a pig's snout for uprooting plants. Though heavily armored, it still actively defends itself, biting and screeching loudly. It can often be heard calling in its guttural, sneeze-like bark, insterspersed with whistling exhalations, in order to communicate with other members of its species, to claim territory, and to attract females. To see one feeding can be quite upsetting, as it powerfully, but discerningly, uproots and devours plants, crudely mastcating them with its stout teeth before swallowing large portions whole.

Darafify Hoplocroc (Hoplosuchus darafifyensis)[]

This forest cousin of the savanna-dwelling rhinoceros hoplocroc is just half the size, around 300kg, with a much reduced nasal horn. Females live in well-defined territories of up to 30 full and half sisters. Males are solitary and nomadic, mating when they chance upon territories during the breeding season. Offspring are laid in communal pits, and raised indiscriminately by mother or aunt. The name was inspired by the large, four, regular osteoderms located on the bottom last row on the sides of the gut. These have a semblance to the eight-teated ox brought to Madagascar by the Arabian giant Darafify in HE Malagasy legend.

Thresher (Seychellosuchus spinifer)[]

The thresher is one of the several hoplocrocs endemic to the Indian Ocean islands, several radiations having departed from Madagascar or India. It forages amidst the forest detritus, feeding on any fungi, fallen fruit or small plant that it comes across, and occasionally on insects and millipedes. Slightly larger than its relative, this crocodylomorph lives in small herds, usually led by a matriarch. Like in most hoplocrocs, the young are fed a type of crop-milk that helps form the complex intestinal flora that aids these animals in digestion. Adults have no natural predators, though the Seychelles crocvar occasionally raids the young.

BAURUSUCHIDAE[]

This is a group of big ambushing meat-eaters with a poorly known but seemingly glorious history that reaches back into the Late Cretaceous, when several baurusuchid species made Outer Gondwana from Home-Earth's Brazil to Pakistan an unsafe place. The most conspicuous features of Baurusuchidae can be found in their theropod-like skull with serrated teeth, uncomfortably reminiscent of a tyrannosaur.

In our timeline, baurusuchids are not found in the Cenozoic; but in Spec, they spread over much of the world in the Eocene, when India had delivered them to the northern continents. By the end of the Eocene, however, the baurusuchids disappeared in the north. Only in Madagascar, the Island of Crocs, have they survived to the present day. There, they have radiated into a number of terrestrial predator niches; they include the largest predators of the island.

Baurusuchids share the body armour and toothy maw of their amphibious relatives, the Neosuchia, but possess an almost erect stance, with all four legs nearly vertically under the body, enabling them to trot quickly over the ground in pursuit of their prey. Like other crocodilians, baurusuchids are cold-blooded, and so all species are ambush predators, relying on camouflage to sneak up on their prey, and bursting into a gallop when the prey is close enough.

Jagator (Arbrosuchus scansorius)[]

The most common group of baurusuchids, the jagators (Arborosuchus), are agile monitor-sized predators with a penchant for climbing. This decidedly un-croc-like lifestyle is an adaptation for hunting the jagators' principal prey, lemurs.

A jagator climbs a tree by running up the trunk, relying on its sharp claws for purchase in the manner of a treerunner or a Home-Earth cat. Once above the ground, the jagator will flatten itself against a branch and wait for a lemur to pass by. Jagators are capable of waiting for days if necessary, but as soon as its prey comes within range, the predator will spring from immobility to blurred speed. The lemur is dispatched with a quick bite to the neck, and the jagator may feast at leisure.

Jagators are strictly solitary, and only associate with each other during a brief and violent mating season, when females boom their invitations into the forest. These "jagator wedding bells" sound rather like the beating of steel drums, and allow males to track down their prospective brides in the confusing maze of the forest canopy.

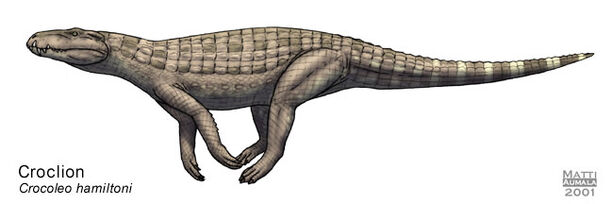

Croclion (Crocoleo hamiltoni)[]

The croclion is the largest Malagasy carnivore. The ancestors of this giant (4-meter-long) terrestrial crocodile were probably similar to the South American †Baurusuchus and †Cynodontosuchus, but the croclion has undergone some modification in its role as the primary hunter of the hoplocrocs.

Croclions' legs are quite long and are held almost straight under the body, enabling these predators to gallop frighteningly fast, even though only for short distances. Their skulls are short (for a crocodile) and deep, and also very lightweight. Croclions hide in the tall grass, waiting for a hoplocroc to amble by, at which point they spring and use their massive jaws to bite through their prey's armor.

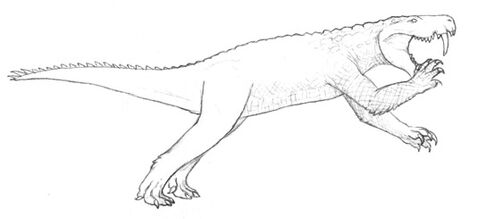

Croctiger (Suchosmilus horridus)[]

The only species of Suchosmilus is the secretive and lethal croctiger (S. horridus). Croctigers are somewhat smaller, but much heavier than their grassland cousins. Their armor plating is extensive, and their bodies are compact and muscular, while the hindlimbs are powerful, and the forelimbs tipped with five curving talons. A croctiger's head is deeper and stronger than that of a croclion, and sports a pair of fangs that protrude several centimeters below the jaw.

All of these adaptations mold the croctiger toward one purpose, hunting sauropods. Though not as large as their cousins on the African mainland, Madagascar's sauropods are nonetheless extremely large herbivores. As they favour streams and the deep forest, are protected by a coat of bony scutes, and are armed with the strength and stamina of all warm-blooded animals, mokeles and Malagasy gihugrongos make challenging prey, but the croctigers are superbly adapted for this purpose.

Unlike any other baurusuchids, croctigers are social, gathering into sibling groups to hunt. These groups wait near game trails for a mokele or young Malagasy gihugrongo to pass, individual croctigers fanned out on both sides of the path, where these cold-blooded stalkers can wait for days. When a sauropod walks past, the croctigers all spring at once, leaping for the neck and flanks, grabbing mokele hide with their teeth and forelimb talons in a burst of activity, then allowing gravity to pull them down, making great slashing wounds. The croctigers then retreat and allow the mokele to stumble off until, weak from blood loss and the infection carried by croctiger bites, it collapses. This final collapse may take place days after and kilometers away from the initial attack, but the croctigers track their prey unerringly with sensitive noses. When the mokele finally dies and the croctigers have gorged themselves, they slink off to their communal nest to sleep off their meal.

Croctiger sibling groups, held together by their common genes, are viciously territorial, swiftly attacking any intruder they smell within its boundaries. During mating season, however, all the males rush of the group rush off to breed with the females of other groups. They return to their own group to help raise their sisters' children, which then either replace the adults or, in times of bounty, run off to form their own groups. Loners of both sexes are not rare, but they tend to be smaller and have low fertility.

EULYCOSUCHIDAE []

This group originates in Australia, the earliest fossils from members of this group have been found in the Miocene of Riversleigh. Even early in their geological history, they exhibit trademark features of the group, long legs, reduced dermal armour, and tall, theropod-like snouts .

Crocwolf (Eulycosuchus ferox)[]

The crocwolf (Eulycosuchus ferox) is the most aggressive and infamous of the eulycosuchids. Found mainly on the lesser Sundas and Sumatra, it was a surprise, to say the least, for early spexplorers to come across such a beast, in an area where dinosaurs were said to be the dominant group. At 4.5 meters long, and commonly weighing in at 45 kilograms, it strikes an imposing figure. It has a fairly typical eulycosuchid bodyplan, and likewise a fairly typical predatory lifestyle, but is more heavily built, its coloring is usually a brown-grey, with dark markings that fade as the beast matures. Despite early assumptions that the animal made no sound, it was later found that the beast made hatchling-like squeaks during mating rituals and at other rare intervals.

Strangely, crocwolves pair for life, but disputes over females can be brutal. The males will begin by defecating and pawing frantiaclly at the ground, the two antagonists will then strut from side to side, sizing eachother up. the next phase of the ritual involves the males rearing on their hindlegs and "boxing" like rutting kangaroos, if a stronger male prevails here the fighting will peter off. However, if the initial bout is evenly matched, all hell breaks loose, males will often try to bite eachother's limbs or tail-tips off, or grab a leg and topple the opponent. Consequently, it is relatively common top see older male crocwolves covered in battle scars, even occasionally missing hands or tail tips. This observation lead to the most remarkable discovery about these creatures, that a member of the pair will often obtain food for their mate if they are impeded by injury. Members of a mated pair tend to hunt alone if both are in good shape, but a mated pair hunting together is a force to be reckoned with. Their most common prey are hogfowl and ornithopods, but smaller animals like gamebirds and lizards often feature in their diet also, like most members of the family they hunt primarily by ambush.

Choo's Crocdog (Cynosuchus chooi)[]

Crocdogs (Cynosuchus sp.) appear strange at first sight. With long, strong cursorial legs, and compact, paw like feet, there's more than a vague passing resemblance to a canid like a dog or jackal. However, these beasts are very much reptillian, with scaly hides, long tails, and strong jaws filled with pointed teeth. These beasts can be found in most Australasian habitats, from dense rainforest to open savannah and desert, though they are far less common than some cedunasaur species.

They feed mainly on vertebrates such as birds, reptiles, mammals and non-avian dinosaurs, they have been observed eating giant earthworms and freshwater crayfish. Due to their lower metabolism compared to endotherms like mammals, dinosaurs and birds, crocdogs eat less for their body weight, they also have a higher rate of reproduction, larger clutch size, and slower growth rate, these factors allow crocdogs to coexist with theropods like warriguls and puffindingos.

In the mating season, they can be fiercely territorial, males often lock jaws and try to topple one another in a feat of strength, but serious injury rarely occurs from such tussles. The most common species, the Choo's Crocdog (Cynosuchus chooi), averages at 3.5 meters long, and usually weighs up to 25 Kilograms. This species has a range over most of the Australian continent, and even ranges as far south as the Flinders ranges. It is coloured a dirty olive brown, with darker blotches and spots over the body, ranging down to stripes and bands along the hips and tail. They are famous for the occasional habit of climbing and resting in trees, which has resulted in many a tall story by overzealous spexplorers. Like most members of the family, they can attain an impressive speed, but cannot sustain it for very long, as such they mainly hunt by ambush.

Laced Crocvar (Varanosuchus robustus)[]

The crocvars (Varanosuchus sp., Choolainia sp.), including the laced crocvar (Varanosuchus robustus) take the role of some larger monitors in Australasia and the Indonesian archipelago. They are adaptable and comparatively quick-witted, being found in most ecosystems, they can run quickly over short distances, and retain the ability to swim well. They exhibit territorial behavior mainly when breeding, or when prey is scarce, they fight mainly by biting each other, though not usually hard enough to make serious damage.

They have an erect stance, a lightly built torso, a long, balancing tail, their legs are long and muscular, though not as long as those of other eulycosuchids, they also possess strong, curved claws on the digits, except the outer two on the forelimbs. Crocvars are generally between 1.5 and 2.5 meters long, weigh up to 7 kilograms, and prey mainly on small mammals, birds, reptiles, and occasionally fish and eggs. The coloration of most species is subdued, usually brown or grey with darker stripes, spots and blotches. Crocvars very frequently climb trees, and can often be seen clambering through the banches. Their mating call is unique, being a tinny, high-pitched "Chik-Chik", earning them their colloquial name, tin-crocs.

- Brian Choo, Daniel Bensen, Matti Aumala and David Marjanović