Living hadrosaurs can be divided into two broad groupings. The neohadrosaurs are, despite their name (which refers to their diversity in the New World), the older and more conservative of the two and are found throughout the Americas and the eastern half of Eurasia (The other great hadrosaur group, the ungulapedes, will be dealt with later). They first appear at the start of the Eocene in North America and are probable descendants of flat-headed Maastrichtian giant saurolophinaes such as the well-studied and famous hadrosaur, Edmontosaurus annectens. In a very short space of time, the clade had spread into Eurasia and South America.

HISTORY[]

Their first wave of expansion in the Eocene was to be a false start. The climatic turmoil at the end of this epoch ended their brief foray into Gondwana while their diversity in Eurasia mysteriously waned as the Oligocene progressed. In North America, evolution continued unabated and they branched into a host of spectacular lineages from giant swamp-dwellers like the big-headed paramegahadrids to speedy two-legged runners such as the flamboyant crested megacaudids. Then disaster struck (literally) at the end of the Oligocene in the form of the Haughton Impact and they entered the Neogene with just two out of six families.

The North American duckbills quickly made up for their losses in the Miocene, once again speciating into giants and midgets (although the small bipeds did not reappear). Their formidable chewing abilities made them particularly well suited to life in the spreading grasslands and, as sea-levels fell in the Pliocene, they launched fresh invasions into Eurasia and South America. However, dinosaurs marched both ways across the land bridges and new competitors and (perhaps) diseases led to a decline in the smaller neohadrosaur lineages. The Ice Ages of the Quaternary led to further extinctions as suitable habitats expanded and contracted with the glaciers.

During the Eocene and Oligocene, North America experienced a hadrosaur boom, with a number of new clades evolving the take the place of the extinct North American ceratopsians, more particullary the members of the Ceratopsidae. As with their distant ungulapede cousins, the neohadrosaurs are united by peculiarities of the manus. With the loss of digit 5, the hand possesses only three fingers, each terminating in a large, hoof-like ungual that is comparatively larger than those of earlier hadrosaurs. In their Cretaceous ancestors, the weight-bearing digits were enclosed within a fleshy pad, but in the neohadrosaurs, the three manual hooves protrude from the flesh and play a greater role in supporting the animal and protecting the forefoot. This may be a relict of the neohadrosaurs' brief foray into bipedalism during the late Paleogene when the fingers were partially freed for defensive and manipulative purposes.

MEGAHADRIDAE (Hmungos, galumphs, hipposaurs, and torgs)[]

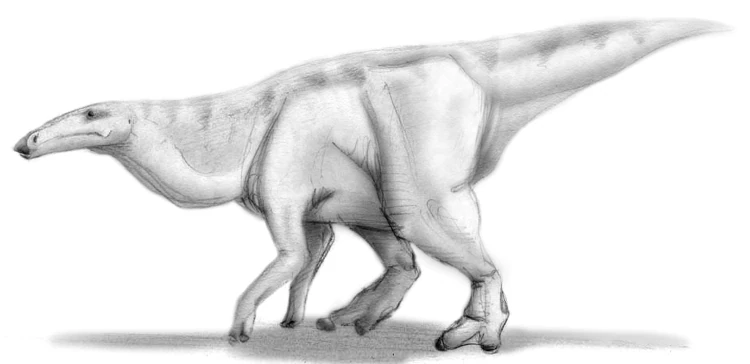

A good chunk of America's hadrosaurs belong to the recently erected Megahadridae. At a glance, these dinosaurs appear quite conservative when compared with their Mesozoic forebears, and for a long time were classified as living representatives of the Cretaceous-Eocene family Hadrosauridae. More detailed studies have revealed that these animals are far more removed from their Cretaceous ancestors than a cursory examination might suggest. Rather than representing a steady progression of the large Cretaceous-type saurolophinae, it is now known that the earliest megahadrids in the Oligocene were medium-sized bipeds, similar to (but not immediately related to) the crested megacaudids. When the big paramegahadrids died out at the end of the Oligocene, the early Megahadridae quickly moved to seal the ecological gap, evolving into the large four-footed forms of today.

With the exception of the primitive galumphs, which can rear up on their hindlimbs, the megahadrids all obligate quadrupeds. The limbs, particularly the forelegs, have become thickened and pillar-like to better support the animals' weight. These graviportal adaptations give them a plodding, elephant-like gate unlike the more dainty motions made by stellasaurs and ungulapedes. All megahadrids tend to be rather slow moving and none can sprint. Thus they tend to rely more on size, a tightly knit herd structure, or aggression for protection (An adult bull hmungo is a far stronger and more solidly built animal than the largest theropod and can do some real damage to a careless tyrannosaur). The vertebrae have been strengthened although the ossified rods found in other duckbills have been reduced. Another unique feature (amongst ornithopods) is the possession of a large and muscular tongue that can quickly and efficiently transfer food from the beak to the cheek batteries.

Present-day megahadrids can be divided into at least 2 subfamilies, the megahadrines and hipposaurs.

MEGAHADRINAE (Hmungos, galumphs, shamblas and bakus)[]

Megahadrines are large (none weigh under 1000kg), but not particularly diverse, with at least several species distributed throughout North and Central America, eastern Eurasia and the northern half of South America. Most likely, these creatures evolved as riverside and swamp herbivores, where they evolved their distinctive short necks and long snouts. This cranial anatomy soon proved to be a useful adaptation not only for dredging up aquatic plants,but for grazing. Megahadrines also possess large and complex nasal chambers giving them a sharp sense of smell and a loudspeaker (and boy do we mean loud!) to keep in touch with other members of the herd or to intimidate enemies.

The two North American galumph species (genus Galumphia) live in the forests of southeastern North America, and look rather like the Mesozoic Edmontosaurus (though they are only distantly related). Despite their name, galumphs are actually quite agile, and can move with surprising speed when threatened, their latterally compressed bodies easily slipping between the trees. These forest browsers feed upon forest undergrowth, shrubs, and saplings, its batteries of diamond-shaped teeth mashing even the ubiquitous Deinorubus brambles into a digestible paste.A galumph's physiology is very similar to that of its Mesozoic ancestors, with relatively weak hind legs, and a center of balance close to the hips. Galumphs never developed the enlarged neural arches over the shoulders (a common feature of many modern quadripedal herbivores) and will often rear onto teier hind legs to reach succulent branches.

Eastern Galumph (Galumphia hebes)[]

With a mass of 5000 kilograms, the eastern galumph is small for a megahadrine, but it is the largest animal in the deciduous forests of eastern North America that are the creatures' home.

Zebra Galumph (Galumphia bicolor)[]

Zebra galumph, Galumphia bicolor (Central America and Northern to Central South America---Cloud forest and Amazon)

Three megahadrine species are to be found in South America. Two of these are southern inhabits of primarily North American forms - a "dwarf" (7 meters long) morph of the greater hmungo and scattered populations of the eastern galumph - both of which are restricted to the north of the continent. The 5 metre-long zebra galumph is, however, an endemic species. These 5-meter pygmies live in the cloud forests of central South America, however, it was recently discovered their range extends to the Amazon and Central America.

Greater Hmungo (Megahadrus titanus)[]

The other group of megahadrines, the hmungos (sometimes allied with the shambala of northeast Eurasia) are larger than their forest cousins, dwelling as grazers on the great interior plains of North America. These elephantine herbivores are highly migratory, and, during the summer, hmungo herds habitually pass only just south of the Arctic Circle.

The upper and lower bills of a hmungo's mouth function as the cutting blades of this living lawnmower. The grass is clipped off near the roots by the beak, and then slid back into the cheeks by means of an extremely long and muscular tongue. Batteries of diamond-shaped grinding teeth (a gift from the hmungos' hadrosaur ancestors) reduce the high-silica vegetable matter to a digestible paste, which is then passed into the crop for further digestion before finally entering the stomach. This peculiarly dinosaurian digestive process is far more efficient than any mammalian system (although Home-Earth's ruminants, with their multiple stomachs, come close) and so hmungos can grow much larger on a diet of grass than can any furry creature.

A herd of greater hmungos and palid singers and menaced by a threesome of pecos draks, Megahadrus titanus, Neostellasaurus pallidus, Paraboreonychus horridus and an unidentified species of viriosaur (central North America---Great Plains)

Greater hmungos (Megaharus titanus) are elephantine grazers, the culmination of the megahadrid radiation of giant grazers. Dwarfing the other herbivores of the plains, greater hmungos most closely resemble the African grassbags in their habits; they are biological vacuum cleaners.

The greater hmungo may be found across the plains of central North America as well as the forests of the west, the small, closely-knit herds migrating past the 60th parallel during the summer and the 30th in the winter. A non-migratory, dwarf subspecies of greater hmungo can even be found in northern South America, as mentioned earlier.

Hmungos mate for life, and roam about the grasslands in pairs or in groups of immediate family. The herds only collect during the spring (northward) migration, when the unmated bulls trumpet their challenges across the prairie, hoping to impress potential mates with the strength of their voices. Courting and mating take place during the move, and by the time the herds have reached their summer breeding grounds in northern Canada, their eggs are ready to be laid. Incubation is short, no more than four weeks, and the young are ready to walk within 14 days of hatching. In the North, the season's turn takes place soon after the hatching, and the hmungo calves have to grow up fast. Many are still wobbling on their feet when the herds begin their migration south, and it is at this time that the hmungo population is most vulnerable to predators. Draks hide in clumps of brush to ambush unwary juveniles, while striders pursue the herds' sick and aged population with lethal dedication.

Despite this periodic thinning of the herds, hmungos generally suffer little predation since they grow up to massive sizes around the same range as giant hadrosaurs from the past. A 14 meter-long, 6000kg bull hmungo is more than a match for any carnivore; even sabre-tyrants, and to an extend, the larger species of draks, tend to leave the giant herbivores alone. However, sabre-tyrants will prey on individual hmungos who are either old, young or sick. Because of the protection they offer by their presence, hmungo family groups often form the nucleus of much larger mutli-species herds composed of singers, vanguards, viriosaurs, and therizinosaurs. Smaller species, such as the hawk-sized hmungo-swoops (Agilifuga rufa) have become totally dependent upon the giant megahadrids and the insects they flush out of the grass.

The hmungo-swoop is one of the larger species of clade Agilifugiiformes, a group of non-passerine, Spec-endemic birds that occupy most of the high-speed-pursuit insectivorous niches in the New World. Even among their kin, hmungo-swoops are particularly agile in the air, as they feed upon the swarms of flying insects that the hmungos' progress stirs up from the grass. These birds highly social, banding together in closely-knit flocks as they herd flying insects into manageable clumps. The hmungo-swoops, executing maneuvers of dazzling complexity, then proceed to snap up the clumps even as they break apart, inhaling insects like avian vacuum cleaners.

Hmungo-swoops may be found across North America, but are most common in grasslands, where they follow the hmungo herds in their endless search for food. Like most agilifugids, hmungo-swoops mate for life, and build their nests from mud, which they cement to the insides of hollow trees or other well-protected, vertical surfaces. No call is known for this species, but studies suggest that they may make use of supersonics for communication.

An organism as large as a hmungo cannot exist without altering its environment. Over the millennia, the grasslands of North America have adapted to the constant grazing of the greater hmungo and its ilk, giving them a distinctly different feel from the relatively untouched prairies of our home timeline. Some prairie grasses are very fast-growing, almost visibly pushing skyward in the spring growing season, relying on their metabolic speed to outpace hmungo appetites. Other species tend to be shorter than on Home-Earth, offering a smaller surface to be gripped between lawnmower jaws. The blades and stalks of all these grasses are high in silicates, with slicing or sawing edges capable of cutting even a hmungo's leathery hide. Older hmungos may carry scars of grass-wounds on their snouts, but the giant herbivores seem not even to notice these defenses, scything through the grasslands as if the saw-toothed blades were not even there.

The hmungos probably do a great deal to preserve their environment, however. Were it not for these leviathans ripping the soil apart, trampling small trees and bushes, and cutting their swaths across the prairie, North America's great grasslands would be a fraction of their current size. In fact, America's sea of grass extends quite a bit farther than those of our own timeline.

Sludger (Megahadrus mississippiensis)[]

Also known as swamp hmungos, sludgers are the second largest species of megahadrid, frequenting the rivers, lakeshores, bayous, swamps and wetlands of southern North America down to Central America, towering over the little kranilis as they scoop vegetable matter into their wide, flat-tipped maws.

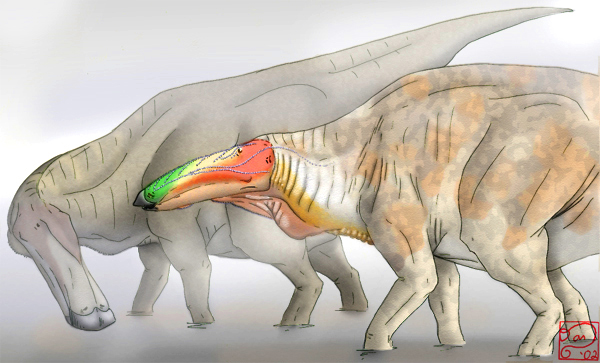

Like their cousins, the greater hmungos, sludgers travel in small family groups with a single mated pair leading a bevy of children and siblings. When the faces of the young males flush with red and green mating colors, they leave the bevy to find females. Upon finding an attractive bride, the young male displays, not to her, but to her father, the bull of the bevy. During the March mating season, old bulls sometimes find themselves surrounded by suitors, each displaying madly.

Least Hmungo (Megahadrus minimus)[]

The least hmungo (Megahadrus minimus) is the smallest member of its genus, three meters high at the shoulder and very lightly built. These hmungos make their home in the semi-arid plains highland forests of the south-western coast of North America, shielded from the rest of the continent by the Rocky Mountains. These hmungos are at home both in the deciduous forests and the plains, leading some to speculate that this species is the link between Megahadrus and Galumphia species, however, this has not yet been confirmed.

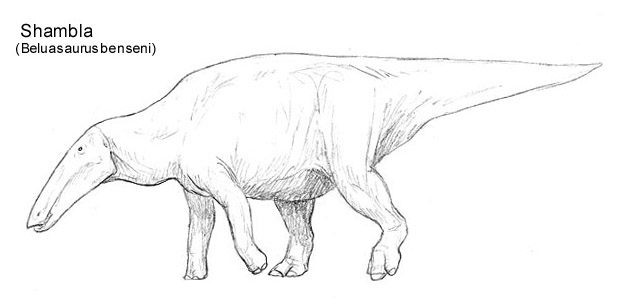

Shambla (Beluasaurus benseni)[]

The shambla is unmistakably a megahadrid, and not related to the Eurasian/African ungulapeds. This old-style herbivore pre-dates the ungulapeds, and represents a Miocene radiation of grass-eating hadrosaur. Shamblas' habits are poorly known and additional species may be awaiting discovery. Strangely, Asia shares no extant megahadrine genera with North America, although there was a significant fossil correspondence early in the Quaternary.

MICROHADRINI[]

This small clade of hadrosaurs are known to live on small islands of Japan and is represented by one species only, the Baku.

Baku (Microhadrus reclusiva)[]

Growing up to 5 feet long, this small species of neohadrosaur dwells in the thick forests of Kyushu and Shikoku. Although more (and larger) species previously existed, they subsequently died out due to competition with therizinosaurs, paraselenodonts, and saurolopes.

During the Miocene, the area that would become Japan laid within the warm temperate climate zone, an area rich in grassland and light woodland, ideal habitat for the megahadrids that had recently arrived from America. When Japan broke off from China during the mid-Pliocene, these megahadrids underwent a light diversification, evolving into Hmungo-like grazers, lightweight browsers, and secretive pygmy species which dwelled in the south. During the Ice Ages of the Pleistocene, landbridges brought in new species from the mainland, including ealines, segnosaurs, boreonychids, sabre-tyrants, etc. This onslaught of invasive herbivores and carnivores spelt doom for most of the Japanese megahadrids. Only in the southern subtropical forests did they continue to survive. Over time, the Baku (Microhadrus reclusiva) regained and lost territory as the warm interglacials came and went and the dense subtropical forests grew and shrank in size. Since the Ice Ages, their stronghold has been the islands of Shikoku and Kyushu, where in the dense, forests they are usually safe from species too big to enter. In these forests they are also safe from most predators, with the biggest threat to them are the tyrannosaurids known as the Oni (Contusisaurus ferox japonicus), which differs from it's mainland relatives in its lighter coloration.

HIPPOSAURINAE (Rawheads, torgs, and snufflelumps)[]

With thirty species, the hipposaurs ("horse lizards" - an allusion to their large hooves and the horse-like whinnying produced by some species) can be found throughout the Americas south of the tundra. While producing a number of supertitans in the past, no living hipposaur comes close to rivaling the giant megahadrine hmungoes in size, but they are all big animals, ranging from 350 to 3500kg in weight.

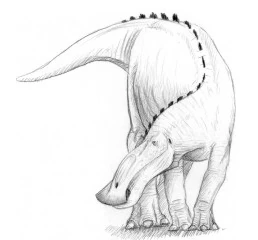

While generally similar to their megahadrine cousins, a number of features distinguish the hipposaurs. They do not gather in massive herds like the hmungoes and, with the exception of the South American torgs, tend to avoid the open habitats, preferring more sheltered environments such as woodlands and swamp forests. While possessing large nasal cavities, the fleshy chambers are not as complex as those in the megahadrines, making the hipposaurs' vocalizations less complex, but no less loud.

The forelimbs are proportionally longer than those of megahadrines and share a greater burdern of bearing the animals' weight. The tail tends to be rather narrow and stubby, possibly because their function as balancing devices is no longer required for these front-heavy herbivores. Finally, while megahadrines are all "smooth-backed", many species of hipposaur possess dorsal ornamentation in the form of triangular osteoderms or elongated scales.

The most notable anatomical feature of the hipposaurs is the almost total loss of the network of ossified rods associated with the neural spines of all other duckbills (these struts are reduced in their megahadrines, but still present). The solid limbs have eliminated the need for these support structures and allowed the tail and torso to become more flexible, a bonus when moving between the tree trunks.

Although originating in North America during the Miocene, the loss of moist woodland habitats at the end of the last Ice Age have made the hipposaurs sparse and scattered on their original home continent. The eight or so hipposaurs, which are native to North America, tend to be rather smaller than their southern counterparts and their distribution is restricted. Scientists point to the arrival of the Yata (Anatobison anatobision), currently one of the few species of formosicornidae native to North America, during mid-Pleistocene epoch in which they competed with the hipposaurs in the area for the same niche. Eventually, the vast majority of North America hipposaurs were driven to extinction by the hoofed invaders during the final days of the Pleistocene epoch. However, not all of the North American hipposaurs were driven into extinction by the arrival of the Yata. As mentioned earlier, only eight species of hipposaurs are left in North America; with the most famous example being the rawhead.

Rawhead (Hycephale longicaudas)[]

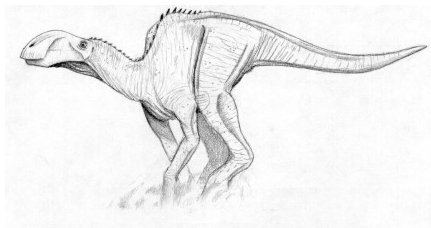

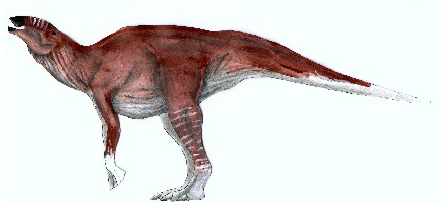

The rawhead reaches a length of just under 6 metres and weighs in at 1.5 tonnes. Unusually gracile for a hipposaurine, it is considered to be the most primitive living representative of that subfamily, with less prominent graviportal features and an unusually long tail. Small rawhead herds dwell in the temperate deciduous forests on the east coast of North America.

Rawheads desperately need to build up reserves of fat during the summer and the long tail provides a large surface area for the buildup of apidose tissue to help see it through the winter. When the snows arrive, the herd huddles together in one spot to conserve energy and the animals spend their time listlessly chewing on twigs.

With the coming of spring, the gaunt rawheads browse ravenously and, with the breeding season imminent, develop the rosy-pink facial colours from which inspired their common name. Breeding leks are loud and violent spectacles as the males club each other with their thickened domed snouts.

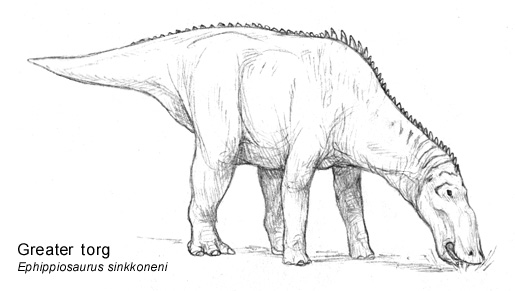

Greater Torg (Epippiosaurus sinkkoneni)[]

It is in South America that today we find the full flowering of hipposaur diversity. With relatively little competition, the twenty-two Neotropical hipposaur species are the most common low-browsers and grazers on the continent. On the open plains to the south of the Amazon, they have produced the torgs, large grazers that echo their hmungo cousins in the North.

The torgs of South America are the only specialized grazers amongst the hipposaurines, and the 3.5 tonne greater torg is the largest and most widely distributed of these hadrosaurs. These creatures dwell in small, closely-knit herds from the Amazon basin south to Spec's pampas grasslands. Smaller than both pachamacs and k'z'ks, greater torgs are far more common than either of these giant herbivores, and can almost always be spotted grazing upon the pampas grasses. Like their North American cousins, the hmungos, greater torg herds are often associated with smaller animals, most notably the fuzz-butts that feed upon herbs uprooted by the hadrosaurs.

Darwin's Torg (Epippiosaurus darwini)[]

With a mass of about 3000 kg the darwin's torg is slightly smaller than the greater torg. These animals migrate across the patagonian pampas alone or in mated pairs. The female darwin's torg lays 3-5 eggs and takes care of her calves for about a year, protecting them from magnoraptor packs the occasional courageous errosaur.

Pampasaur (Pampasaurus gigas)[]

With a mass of about 2500 kg, the pampasaur (Pampasaurus gigas) is one of the largest of the hipposaurs, sharing many features with the North American hmungos and the South American torgs. These animals display similair behaviors to the likes for the Darwin's Torg, from migrating the pampas and protecting their offspring from predators.

Snufflelump (Longicephaloides inexpectatus)[]

With its compact, heavy-set body, awkward plodding gait, beady-little eyes and extraordinary long, narrow bill, the snufflelump is about as weird as they come. This solitary animal roots around on the forest floor, probing into the leaf litter with its schnozz in search of roots, tubers, fungi and fallen fruit. During times of flood, it wades in the shallows, consuming entire seedlings and small shrubs by plunging its beak into the soft mud to grasp the plant by the roots. Like the frill tusker and the spineback kentropod, this remarkable half-tonne hadrosaur is a secretive and poorly known denizen of the South America's tropical jungles.

STELLOSAURIDAE (Grasbucks and Singers)[]

Singers and grasbucks represent the last remnant of the the once-great American diversity of small hadrosaurs. These dinosaurs formerly occupied all the small herbivore niches in North America, as well (the smallest known stellosaur from the final days of the Oligocene, the most noticeable example being that of Microstellosaurus agilis, which most likely weighed less than 10 kg), but these forms have been largely pre-empted by the viriosaurs from the South and the dwarf therizinosaurs from the North. Additionally, a number of larger forms (over 500kg in weight) were around during the Pliocene and early Quaternary. They are (apparently) restricted to warm-temperate to tropical North America although the fossil evidence suggests that they once ranged from the Subarctic to Patagonia. Whiles the subarctic species eventually succumbed to the climate change during the Pleistocene Ice Age, it appears that the South American species managed to fair better and thrive in that environment. With recent expeditions to back to Spec's South America are suggesting that a group of singers, referred to as "notostellasaurs" aka "southern star lizards", might exist in the rain-forests and grasslands of South America; including a species that might be native to Central America. However, several people in the spec community have their doubts about the existence of these enigmatic singers, mostly due to the fact that the only existence of these species is a a series of audio recordings, matching the painted singers, and footprint casts of these creatures which do not match the largest viriosaurs that inhabit South America. The main issue is that a lack of photographic evidence for these South American singers has caused their existence to be questionable. It is believed that several expeditions, consisting of some of the best researchers, biologists and paleontologists, back to Central and South America's less explored regions will settle this debate once and for all.

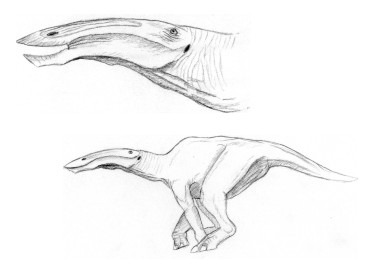

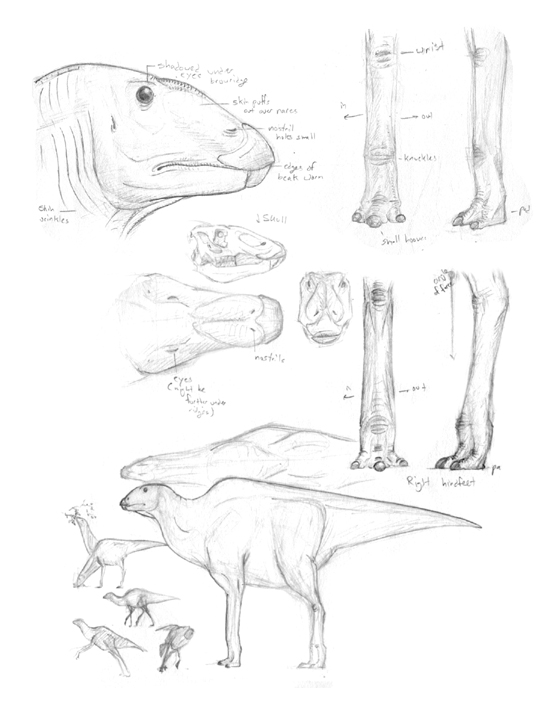

Fossil and morphological evidence suggests that the stellosaurines split off the main neohadrosaur line early in the Cenozoic, although they do not appear in the fossil record until the very end of the Oligocene. These dinosaurs are easily distinguished from their relatives, the megahadrids by the the bizarre construction of their respiratory passages, which resemble nothing so much as those of a bird. Stellosaurines, of course, do not possess the air sac system of their distant cousins, but their larynx (voice box) has evolved in startling convergence with the avian syrinx. With the aid of their modified vocal chords, stellosaurines can produce a wide range of bird-like calls that are easily differentiable from those of other hadrosauroids, which use their nasal passages rather than their voice boxes as resonating chambers.

Today, the singers occupy most of the small-to-medium herbivore niches in central, southern and western North America, with some competition from the therizinosaurs. With their kritosaur-like appearance, these creatures are most common in the great American prairies, but can be found in enclaves across the continent, recently some have been as far down as Northern South America. Even as far north as the 60th parallel, therizinosaurs, the summer sun brings vast herds of migratory herds of grasbucks, another nomadic species of small hadrosaur.

GRAMESAURINAE (Grasbucks)[]

The Grasbucks are widespread grazers, ranging from the plains of central North America all the way down to the grasslands of South America. They can be found in all the tropical and subtropical open grass ecosystems of the continent, with a few living in more temperate areas. One species even is an exclusive endemic of Hmungo halls. These 200 to 400 kilo herbivores form large herds ranging between 100 to 10,000 individuals that range across the plains. Twice a year, bucks bugle their desire to the does, with the females dropping 15 to 40 eggs in concealed scrapped over mounds before moving on. The surviving eggs hatch out some three months later with the chicks forming crèches. After a year or so, the rapidly maturing juveniles join adult herds passing by.

American Grasbuck (Gramesaurus americanus)[]

Also known as the common grasbuck, the american grasbuck (Gramesaurus americanus) is the most common and well-known species of the singers. These selective grazers form small herds that migrate across the North American prairies, often heralding the arrival of larger animals such as painted singers and hmungos. A nomadic species, grasbucks migrate from southern North America as far north as the 60th parallel as the seasons change.

Cerrado Grasbuck (Gramesaurus braziliensis)[]

The Cerrado Grasbuck forms herds numbering up to hundred. These animals move across the Brazilian plains in unending seasonal migrations. The bucks develop a colorful red blush on their necks during the biannual breeding seasons. Spexplorers who come upon males who have seduced females, compare the verbal interchange to Tibetan monks reciting the universal sound of "aum".

Hall Grasbuck (Gramesaurus hmungasectus)[]

The Hmungos are powerful hadrosaurid giants who clear out pathways hundreds of kilometers in length across the prairies, much like Old World grassbags. In the the hmungo pathways of southern North America, Hall Grasbuck from follows hmungos in small herds of 10 to 20 feeding on the exposed growth the hadrosaurids have uncovered. Hall grasbucks flute high bugles every six months or so, with the males flushing neon green around their necks and shoulders. The eggs are promptly laid in concealed mounds within large scrubby stands and abandoned.

Texas Grasbuck (Gramesaurus mexicanus)[]

Texas grasbucks are found in Mexican dry forests, savannahs and scrub north into eastern Texas. From eastern Texas, colonies can be had hugging the coastal grasslands until Florida, where modest-sized herds of 50 to 100 wander the central scrub and grasses; a similar range occurs along the Pacific coast up to southern California and the Baja Peninsula, albeit far less coastal. Eggs are laid once a year in June, abandoned and hatch in late August. The crèches shelter in dogbunny, bastardsloth and meiolanid burrows from late November until March. By their 1st birthday, the chicks join passing adult herds. Their second winter has them fatted up and developing longer quills, the chocolate brown coat around the body being molted into a bristlier version. By their fourth year, Texas grasbucks are at their adult weight of 200 kilos, though very old individuals may reach nearly 50 kilos more over time, and generally lose most of their coat during the Summer, except for purple patches, coloured so due to unique iridescent quills.

STELLOSAURINAE (Singers)[]

Stellosaurs, or singers, are among the smallest, most graceful living hadrosaurs, a stark contrast against the usual hadrosaur tendency to increase in size and bulk. First evolving in the Oligocene, these animals took advantage of the first appearence of open plain biomes. For 26 million years they ruled plain ecosystems in South America alongside mammalian un-ungulates, and while a good chunk of their diversity went right throught the window in the late Miocene and later in the Pliocene, they still remain North America's most adaptable ornithopods, ranging from Alberta to Argentina, being most common in temperate and woodland galleries and savannahs of both Americas, occupying an ecological niches akin to those of extinct HE camelids and liptoterns. Singers have gorgeous voices, with chirps, bugles and roars that can vibrate through your core, hence their vernacular designation. This is due to an unique set of air sacs coming right off the trachea - and adaptation that has arised seemingly independently in vans, duckgongs, jackalopes and some ceratopsians -, having chambered and arraigned them along their trachea and larynx. The larynx itself has developed a great degree of convergence with the avian syrinx, although it is placed well above the brachial divergence in stellosaurs. Nevertheless, singers have a very powerfully muscled vocal apparatus that can be played like a fine tuned orchestra. An entire herd at full pained, rutting blast can reduce human observers to a dumbstruck audience. While Spec has affected all who have visited, it is stated that a year with the rhythms of the grasbucks can give one enlightenment.

The "true" stellosaurs, bucks with orgasmically patterned skin shining during the rutting season; intensive care of the chicks by the males and unparalleled refinement of the syrinx. Starry singers are found browsing within the massive hmungos. One aspect of this adaptation is the increased care provided to offspring.

Tule Singer (Nothusafilius impirium)[]

One main species of singer is found in the central Californian valley system. The central valley singer is quite distinct from its cousins elsewhere, and it is thought to be the last member of an early north american radiation that may predate the interchange. Tule Singers often roam well into the Californian foothills in the summer, grazing as they go in herds of 15 to 25. Winter has them retreating down into dry highlands near the incalculably vast tule wetlands. By late November/early December, the 70 kilo Tule Singers huddle together in camouflaged burrows lined with dry leaves and mosses, where they spend the colder winter nights. These burrows are often expansions on abandoned bastardsloth or diggadum warrens. It is not uncommon for the mammals to be spending the winter right alongside the dinosaurs. No other hadrosaur digs borrows, and for the most part these dinosaurs simply expand already existing burrows by digging with their beaks. While this seems to be an extreme reaction, it is thought that the ancestors of the Tule Singer evolved under the influence of the worst glacial periods, which made the now temperate californian climate much more arid and cold. These fleet footed, graceful herbivores eat a variety of plant material, including such unpalatable such as wood urchins (Orbuligna sp.) and sagebrush. Tule singers communicate within and between herds with their voices; which, due to their stellosaurid syrinxes, are quite variable. Recordings of singer "conversations" within a single herd in the San Joachin Valley have been made, and some last for hours, but what meaning these vocalizations convey is unknown. When spring arrives in March, the bucks begin jostling and bugling at each other. Eventually, the warmth of April stimulates the does into egg production. Dominant bucks will mate with as many as twelve does at a time. The females scrape together concealed mounds of rotten vegetation and dirt together to lay up to 30 eggs in. The bucks follow every female within their territory when they construct these mounds and finish laying. The does promptly abandon the eggs and proceed to fatten up on the new spring growth. The buck on the other hand, must browse sparingly for the next two months as he waits for the eggs to hatch. Late May/early June sees the chicks scrabble out of their mounds and dash into the deepest undergrowth. One would think the buck's duties would over at this point, far from it, the poor male must now look over up to 200 little hatchlings for the remainder of the summer. Even the most valiantly protective father cannot prevent the extreme winnowing that occurs every year due to predation, starvation, accidents or weather related phenomenon. Still, a good father often has 30 to 50 half grown chicks by autumn. The well seasoned and educated survivors of the crèche leave by September to find their own burrows. They often utilize the abandoned burrows of a different bastardsloth species than their adult co-specifics.

Valley Singer (Stellosaurus valensis)[]

Equally at home in forests or the dry grasslands of the Sierra rain-shadow, the valley singer is ubiquitous across the southern portion of North America's west coast. Valley singers are isolated from other singer populations by the Rocky mountains, and so are often the only herbivores of any size in their environments (although some parts of their range overlap with the least hmungo). These fleet footed, graceful herbivores eat a variety of plant material, including such unpalatable of wood urchins and sagebrush.

Valley singers are not as social as grasbucks, but they do tend to gather in small herds of no more than a dozen individuals, and have no apparent hierarchy of power among adults. Valley singers communicate within and between herds with their voices, which, due to their stellosaurid syrinxes, are quite variable. Recordings of singer 'conversations' within a single herd in the San Joaquin Valley have been made, and some last for hours, but what meaning these vocalizations convey is unknown.

Starry Singer (Stellasaurus communicatorius)[]

The starry singer is not a prairie species, but inhabits the deep deciduous hardwood forests of the southern part of North America. As the creature is a forest dweller, it lacks the flat tipped beak of the hmungos, having evolved to feed upon low flowering bushes. They can occasionally mix with hmungo and other singer herds.

This singer's skin, patterned with dark colors and light bands, helps it to camouflage from potential predators, its disruptive pattern will splendidly blend them with the surroundings. This dinosaur exhibits distinct sexual dimorphism, males having a much more heavily spotted skin and a thicker nose bump and being rather smaller than the females. Males also adopt a black mask during the courtship period. The females often form small groups (reports telling of 4 females and respective calves if any) with only one dominant adult male (other adult and juvenile males with no harem usually go solitary or in pairs). The singer's specific name indicates a curious characteristic of this dinosaur. Like other stellosaurs, starry singers make use of their birdlike vocal organs to communicate with each other. Males have a rich repertoire, which is only used during the breeding season. Each "song" has a specific purpose. One is used by a dominant male to keep other males at distance, one other may be used to find a lost element of the herd, and so on.This dinosaur cannot be confused with any other in the forest, because of its bright stripes of spots which give the dinosaur its name. Several pattern variants are known. Walking through a singer-inhabited forest, one can easily miss the animals, superbly camouflaged as they are, but one will probably hear their beautiful singing.

Painted Singer (Neostellasaurus pictus)[]

Another member of the singer complex, the painted singer is closely related to the plaid singer. This species primarily dwells in the prairie and in outer ridges or forests, usually along the course of rivers. Thought not as vocally talented as the starry singer, this species is also strongly vocal, music consisting in metallic clicks and high pitched sounds, and an occasional thunder like roar used by the male to alert the herd of adjacent dangers.

Painted singers gather into gigantic collections, often forming mixed herds with hmungos and other hadrosaurid species in search for tall grasses and flowering bushes in spring and summer. A three ton, twenty feet long, alpha bull leads the herd, commanding the respect of the other male members. These bulls often engage in ritualized dominance fights, where they flash the striking pale dots along their flanks. The females, while still roughly the same size as the bulls are whitish brown in color.Two main of painted singer are currently recognized:

Red-Crested Singer (Neostellasaurus pictus sanguineocristatus)[]

This subspecies lives in southern most part of the united states species range from Southern North America through out Central America. It is possibly this could be enigmatic subspecies of painted singer in South America known from its haunting yet beautiful songs which echo through out the dense and unknown rainforests of the Amazon. However, it is difficult to say with the lack of evidence and the more recent expeditions in Spec's South America still in their earlier stages.

Nomadic Singer (Neostellasaurus pictus pallidus)[]

A much drabber subspecies which is generally found in the northern most part of the species distribution range.This last subspecies is partly nomadic and both subspecies can be seen together in the summer months when Neostellasaurus pictus pallidus migrates south, the name is not to be confused the the subspecies of Pale Singer.

Pale Singer (Neostellasaurus pallidus)[]

Pale singers (and their cousins, the painted singers) are remarkable for their extreme sexual dimorphism, expressed as brilliant "dominance colors" in a herd's alpha male. A year after being born, young males rapidly increase in size, and the bulls will attain their adult masses at 5 years, at which point they are sexually mature. Cows, however, reach adulthood at 3 years of age, although they rarely lay eggs before their fifth year.

Upon reaching sexual maturity, bulls begin to engage in dominance battles, the losers forming small fraternal herds and parting from the main herd body. Most often, the only males in a large herd are subadults and a single alpha bull, who is constantly challenged by younger suitors. The resident bull almost always wins these battles, but even these big bulls will get old (thought they may reach over 100 years) and younger males may get lucky.

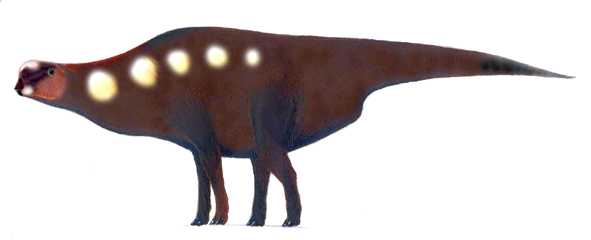

Although males might have secured a "house" by their 6th year; they don't really begin their mastership as fathers until their 8th or even 10th year. This decade long journeymanship allows fully mature bulls to win in dominance fights. Mature bulls who win over their neighbors and are consistently successful at repealing gangs of young bucks also rapidly develop dominance spots. If a young bull manages to defeat a resident alpha, its body changes suddenly and in a few weeks into its "dominance coloration". While of pale brown coloration when adolescent, a new alpha bull's hide will darken quickly upon his rise to power. After a few weeks, five buff splashes appear on both frontal flanks, his cheeks turn into rusty red, the frontal part and forehead become black, the tip of the muzzle and the chin pale to white. The hump increases in size and the neck skin dewlap turns scarlet on the upper fringe. A full adult male pallid singer is a truly spectacular sight.....now imagining two bulls fighting.

In Closing: In Regards to the Existence of Central and Southern American Stellosaurs[]

The perennial question as to the existence of a stellosaurs in the highland tropical mist forests of South America remains a controversial topic amongst specbiologists. No human has ever set eyes upon a living South American singer although fossils of several large Early Quaternary forms are known from Patagonia, it is possible that while some went extinct due to competition from the larger and more successful hipposaurs, the torgs being the best example, some species might have survived the invasion of various species. A haunting, flute-like song has been recorded on several occasions near Cerro Neblina, drifting through the early morning highland mists. The creator of these sounds has never been seen but the song shares sequential similarities to that of the the North American painted singer. Casts and photographs of small quadrupedal ornithopod tracks have also been produced from the region which does not seem to belong to any known viriosaur. Many authorities remains skeptical and the capture of this animal on film or in the flesh has become a sort of holy grail for specryptozoologists. An expedition back to South America and more detailed research in Central America will settle this debate for good.