"This was the most bizarre creature I had ever laid eyes upon."

The rayback is a common, predatory, plains-dwelling, liquivorous bipedalien from Darwin IV, first discovered on January 11, 2358, during the First Darwinian Expedition, in Planitia Borealis, about 70 kilometers from where Barlowe first landed on the planet. They usually hunt solitarily, but sometimes they will use cooperative hunting to take down certain prey. It is a smaller relative of the arrowtongue, though the Rayback occupies a slightly different feeding niche upon the open plains of Darwin IV. It is known to weigh 13-odd tons. Supposedly, it may also be one of the few creatures on Darwin IV to have two sexes rather than be hermaphroditic, but this is unconfirmed.

It is a leathery-skinned biped with four elongated spines protruding from its broad back. When resting, it squats close to the ground. Like all Darwin IV creatures, it does not have any eyes on its triangular head. Instead, it navigates with a barrage of high-pitched sonar pings when needed.

When a rayback quickens its pace to a fast trot, leaping over broad ravines and pushing through the thick grass with ease, it can bring its speed up to a formidable 45 kilometers per hour (almost to 50) and can cover the terrain of the plains with great leaps.

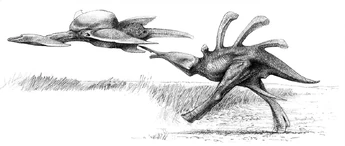

Most of Darwin IV's predators are highly specialized and selective in their choice of prey, but the illtempered rayback will go after anything that moves, such as the hammer-headed veldt-wing shown here. The first one Barlowe encountered repeatedly attacked his hovercone.

In pursuit of prey, a rayback can cover almost 5 kilometers, with both animals careening in wide turns and bounding over rocks and depressions. Even though a rayback can be clocked at 48 kilometers per hour, certain difficult prey as gyrosprinters can race at nearly twice that speed. If a chase begins at closer range that outcome might be different, but, Sometimes, a Rayback's chases after prey can turn out unsuccessful. With heaving sides it will break off the hunt and trot to a halt; then it kneels down and rests in its squatted position. However, it does not always give up. It will often keep searching for prey, walking along and pinging occasionally while on a searching hunt. A rayback will end its chase for prey using its short, knifelike proboscis to slice a huge, crippling wound into the side of its prey. The prey animal, now trailing its entrails, will collapse in a cloud of dust. The triumphant rayback trots up to it and hunkers down to feed. This is accomplished by the liquivore inserting its tongue deep within its victim. Persistence can pay off for a hungry rayback.

Faster and more agile than an arrowtongue, the rayback can outsprint the arrowtongue and, as a result, can tackle prey such as low-feeding flyers, young herd animals or ambushed Gyrosprinters. Notable for its particularly unpleasant temper, raybacks will charge virtually anything that gets too near

Sometimes, however, they themselves can become prey to larger predators, such as Eosapiens.

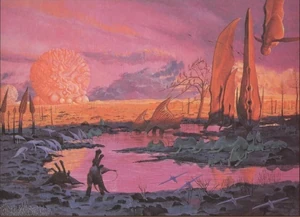

A rayback at dusk.

Two Raybacks join other creatures at a rare dryland waterhole, the diverse species gathering in relative peace here. A pair of Brain-balls - huge, colonial, earthbound floaters - approach in the distance.