Rivaling the dinosaurs as the most famous prehistoric animals are the great marine reptiles that mastered the Mesozoic oceans. On Home-Earth, the sea turtles are a sole reminder of a lost age when sauropsids ruled the waves. Beneath the waters of Spec, however, the turtles are joined by another, far less benign lineage from the Cretaceous, the fearsome mosasaurs.

Mosasaurs are aquatic anguimorph lizards related to monitors and snakes, falling phyletically somewhere in between them. They are found throughout the warmer waters of the world, ranging in size from 2 to over 20 metres in length. Their bodies have become superbly adapted to aquatic life, with all four limbs had evolved into hydrodynamic paddles that are lengthened by an increased number of phalanges. All species are ovoviviparous, giving birth to live young thus eliminating the need to come ashore.

Both the skull and lower jaw have special hinges that create a massive bite combined with a surprising degree of fine manipulation - a mosasaur can break open an ammonite shell and gobble down the contents without shattering it. The variety of dentition displayed by modern mosasaurs far outdoes any other lizard group, ranging from densely packed needles to sparse crushing pegs.

Most mosasaurs have good eyesight and hearing but, in extant forms at least, the strongest sense appears to be chemoreception. All mosasaurs possess a well developed set of Jacobson's organs that allows them to "smell" the water by passing it over the roof of the mouth. Although their underwater sense of smell has yet to be scientifically quantified, it appears to rival that of sharks in that dumping chum on the surface of the Spec sea will attract every lizardwhale for miles around.

HISTORY[]

Mosasaurs evolved from smaller lizards called aigialosaurs that took the water during the mid-Cretaceous. Rapidly increasing in size and diversity, the early mosasaurs soon became top marine predators and spread across the globe. This first generation were sinuous creatures with short paddles and a long, flattened tail that swam with an undulating motion much like a crocodile or snake.

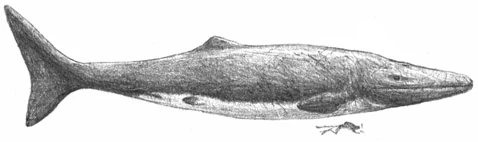

(fig. 1) Moanasaurus mangahoungae, a typical Late Cretaceous mosasaur.

Not designed for prolonged chases, they probably ambushed prey with sudden bursts of speed. Monsters like Hainosaurus and Tylosaurus terrorized the Maastrichtian seas from the Netherlands to New Zealand but, despite all their evolutionary vigor, were obliterated by the KT catastrophe of Home Earth. Perhaps this was in part for being largely restricted to the continental shelves and inland seas whose ecosystems were hit particularly hard.

In the early Cenozoic of Spec, mosasaurs continued to flourish and diversify while many other aquatic reptiles, like elasmosaurs and polycotylids, went into decline. 20 meter long tylosaurines cruised the Eocene seas from the shores of the Tethys to the warm Antarctic coast. But these relics of the Cretaceous were condemned by the climatic chaos that struck the Late Eocene world. Just as the serpentine archaeocete whales of our timeline perished at this time, so too did their reptilian counterparts on Spec.

(fig. 2) Balaenanguis, an Eocene mosasaur that began to acquire specializations for a pelagic lifestyle.

However the Late Eocene proved to be a new beginning for the clade, for other mosasaurs had branched into different habitats and body-forms that made them better able to endure those troubled times. Some took the elongated body-form of their ancestors to the next level, becoming serpentine masters of murky, weed-choked rivers. Another group took to the open ocean, turning their bodies into piscine torpedoes that could outswim their fastest prey.

Today, a dazzling array of mosasaurs can be found from the equator to the warm-temperate waters across the globe. While barred from the polar regions owing to their cold-blooded metabolisms, the size and variety of Spec's modern Mosasauria puts their Cretaceous ancestors to shame. They can be divided into two broad groupings; the Anguillacertia and the Saurocetaciodea.

ANGUILLACERTIA (River Mosasaurs)[]

While not a monophyletic grouping, the two families of river mosasaurs are so similar in appearance and lifestyle that they are considered together here for purposes of convenience. Both groups contain gracile piscivores that dwell in major river systems. They are secretive animals that are difficult to observe in the wild.

All river mosasaurs have adaptations that facilitate the capture of fish. The snout is elongated with numerous small, pointed teeth. The long, flexible body allows them to manouver in confined spaces while, unlike saurocetaceans, the neck vertebrae are unfused, allowing the head to pivot in relation to the rest of the body. Their eyes are small but fully functional while the body is covered with small granular scales, much like those that cover a monitor lizard.

ANGUILLACERTIDAE (Asian river mosasaurs)[]

Ti-Lung (Anguillacerta sinensis)[]

Also known as Panlong, these enigmatic creatures live in the murky rivers of tropical and subtropical Asia, infrequently entering estuarine and nearshore marine environments. They are notable for their extremely compact torsos and long, laterally flattened tails that comprise more than half of the total length. They are unique among living mosasaurs in lacking any vestige of the hindlimbs and in lacking a dorsal fin. Poorly understood compared to other mosasaurs, we currently know little of their exact distribution, life history and evolutionary relationships. Even the number of species is subject to dispute.

The ti-lung is the northernmost of the river mosasaurs and is restricted to eastern China where it is found from the mouth of the Changjiang (Yangtze) to Yichang.

Less than 3 meters long, the Ti-Lung appears to be largely solitary although feeding aggregations of up to a dozen animals are sometimes reported. They often patrol the downstream sections of large sandbars where eddies in the current create zones of high productivity that attract numerous fish. Benthic species, like catfish, appear to be the favored prey.

Naga (Opidocetoides longus)[]

The Naga (Opidocetoides longus) is the most prevalent of Gangetic anguillacertids. At a staggering 9 meters it is very long and slim and feeds mainly on eels and other serpentine creatures, including caecelians. It's threatening behavior is unique, it will swim into a comfortable position near the aggressor, then it will rear up to the full extent of which at can protrude from the water. It hisses ferociously, and will not hesitate to bite. It' snout is long and pointed, with long, intermeshing teeth.

ARCHAEOSAUROCETIDAE (Apep)[]

Nile Mosasaur (Apep aegyptianus)[]

Unlike the Asian river mosasaurs, the apep does appear to be a distant relative of the fish-like lizardwhales and is the sole survivor of a once diverse family of mosasaurs which may have given rise to the true saurocetaceans.

The sole living species differs from the anguillacertids in having a long trunk, small hind flippers, and a small, triangular dorsal fin. The tail comprises about half of the total body length and has a uniquely shaped spatulate fluke. The needle-like teeth are comparatively large and these aggressive hunters will tackle quite large prey.

The apep makes it's home throughout the Nile River system north of the rift lakes, from the vast Sudd swamp in the south to the Nile Delta in the north. Throughout this extensive range, the apep dwells in a wide range of riverine habitats, displaying a preference for deep flowing water. It hunts a wide variety of prey including fish, water birds and turtles. Commonly found at 2-3 meters in length, venerable 4 meter individuals are not unheard of.

SAUROCETACIODEA (Saurocetaceans)[]

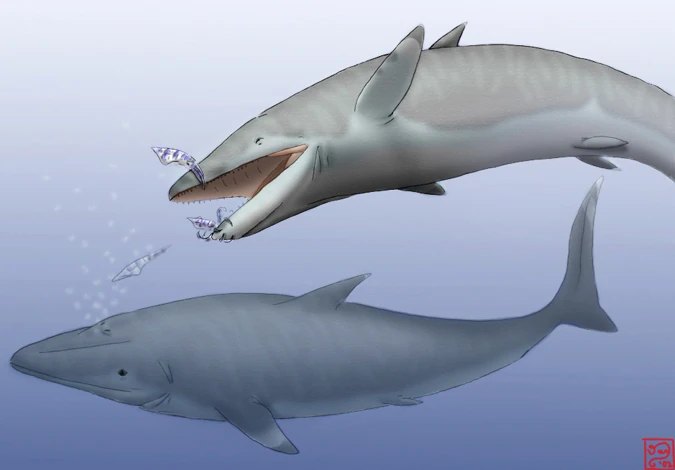

A prownose lizardwhale (Saurocetus pelagios) breaches off the Pilbara coast, Western Australia (photo by Brian Choo)

The saurocetaceans are the most highly specialized marine reptiles alive today, perhaps of all time. The clade contains two distinct lineages, one which produced the ungainly Hobb's leviathan and the other the sleek lizardwhales. The distalmost spinal columns of all saurocetaceans kinks upwards to support a large, falcate caudal-fin. The ribs are loosely attached to the spine via rods of cartilage, giving the flexibility required ,to avoid compression-related damage in deep water. A thick layer of subcutaneous blubber provides insulation, allowing the cold-blooded mosasaurs to hunt in the cool depths of the ocean after which it "recharges" by basking at the surface.

Sauroceteceans have the smallest lung capacity proportionate to their body size of any lizard. A large lung is of little use to a deep-diving oceanic reptile as water pressure at depth compresses any gas in the lungs to almost nothingness (the lungs in fact collapse completely below a depth of 100m). The extremely dark flesh of a saurocete reveals muscles that are packed with myoglobin, attracting oxygen out of the bloodstream and storing it for later use during a dive.

The sauroplacoid scales of a mosark (Pristrix monstrum)

From a distance, a saurocetacean appears completely smooth and naked. A closer look reveals that the reptile is covered in a coat of minute tooth-like scales that look remarkably similar to the placoid scales of sharks. The arrangement of these tiny scales reduces water turbulence adjacent to the body surface and thus increases swimming efficiency. Unlike shark scales, which are individual structures of enamel and dentine, those of saurocetaceans are complex localized thickenings on a continuous epidermal sheet of keratin.

GIGANTOSERPENTIDAE (Hobbe's leviathan)[]

Hobb's Leviathan (Gigantoserpens microdon)[]

The first evidence of one of Spec's strangest creatures washed up on a beach in east Africa one particularly stormy night. The discoverer, a certain Calvin Hobb, was apparently walking foolishly close to the choppy shoreline when a sudden, violent surge practically dumped the specimen at his feet. It was a cylindrical mass of rotting flesh, over twelve meters in length. Within one end of the carcass was the two-meter long skull minus the lower jaw, the vertebral column up to the 17th dorsal, and parts of the right forepaddle. An examination of the bones made it clear that the carcass, now dubbed "Hobb's Leviathan", represented a new species of mosasaur. Initial reports suggested that it was a "living fossil", an archaic long-bodied mosasaurid that had escaped the Eocene extinction. More cautious researchers noted apparent similarities with the needle-like teeth and gracile body-form of the panlong, suggesting a relationship with anguillacertids. While the arguments raged, the carcass was christened Gigantoserpens microdon, "the teeny-toothed gigantic serpent".

The idea of a giant sea-serpent was irresistible and popular reconstructions depicted the animal as a vast eel-like creature with a length of over 25 meters. Nothing more was known of the real leviathan for over three years until crewmen on a vessel surveying the Pacific coast of South America produced blurry photographs of a huge sea creature near San Ambrosio. They appeared to show nothing less than a supposedly extinct long-necked plesiosaur, a beast that seemed to possess a small head, long-neck and a bulbous, flippered body. An expedition to learn more of this creature was hastily dispatched and it was soon ascertained that these "plesiosaurs" were in fact the real Hobb's leviathans.

A live Gigantoserpens photographed off the west coast of South America. At "only" 12 meters in length, this is a relatively small individual.

Skeletal silhouette of Hobb's leviathan by Brian Choo alongside the incomplete holotype specimen and a human diver (diver courtesy Tiina Aumala)

The true appearance of these giants was completely unexpected and nothing like the snake-like hypothetical reconstructions. Rather than a relic of the Eocene or some giant ocean-going river-mosasaur, Gigantoserpens turned out to be a highly aberrant true-saurocetean although different enough to be placed, along with subsequently discovered fossil forms, into the new clade Gigantoserpentidae.

Gigantoserpens is a bizarre saurocetacean that can weigh an estimated 50 metric tons and reach a length of over 21 meters, making it the longest known squamate. The head is comparatively small and flat, sitting on a very short neck behind which sprout a pair of small flippers. These are often held flush against the neck and can be difficult to discern from a distance.

The anterior dorsal vertebrae are lightweight while the associated ribs are greatly reduced in size. The forequarters appear slender and snake-like, creating the illusion of an elongated neck. Further down the trunk the vertebrae become drastically larger and more robust while the length and girth of the ribs increases, causing the body to balloon out. The pelvic girdle and hindf lippers are incredibly large by mosasaur standards whilst the tail is exceptionally long and deep with prominent lateral keels, terminating in a huge caudal-fin. A low, triangular dorsal fin is located midway along the tail.

The dentition consists of numerous fine needle-like teeth and the lower jaw is loosely attached to the skull allowing for a very wide gape. The interior of the mouth contains a series of photophores which are infested with growths of luminescent bacteria that are clearly visible when the jaws are opened.

Frontal view of the open mouth showing the oral photophores - membrane-covered rugosities on which grow clusters of luminescent bacteria. The pterygoid teeth in this species have been reduced to a small row of nodules that are not externally visible on large adults. (right) The appearance of glowing photophores in the darkness of the deep sea. The precise arrangement varies between individuals.

One unusual internal feature is a large sac on the lower intestine that can be filled with over 90 litres of reddish-brown syrupy fecal matter. When threatened by a large carnivore, this liquid is expelled in a great, dense cloud that confuses or repels the attacker and gives the slow-moving leviathan the chance of escape. A similar strategy is used (on a much smaller scale) by the Home-Earth pygmy sperm whales of the family Kogiidae.

The leviathan is a sluggish meso-bathypelagic predator. Based on the stomach contents of stranded individuals, it feeds on non-shelly pelagic prey of up to a meter in length. While it has yet to be witnessed, it's feeding strategy probably involves cruising with its jaws agape. The twinkling oral photophores give the impression of a swarm of bioluminescent plankton which attracts fish, shrimp and squid to within easy striking distance. The slender forequarters can curl and dart around with great speed, allowing it to snap up faster-swimming prey. The giant hindf lippers are used for stability and steering, effectively filling the role of pectoral fins on a more conventional sea creature. The stubby forepaddles seem to act as canard foreplanes, conferring a degree of hydrodynamic stability to the anterior of the animal when on the move. While feeding, they are probably held conformally to avoid drag as the neck sweeps around.

Strandings and sightings indicate a cosmopolitan species of deep offshore tropical to warm temperate seas. Although sparsely distributed, they are sometimes found in large feeding concentrations and appear to have a habitat requirement for deep slope waters with steep depth gradients. When not breathing or basking, they follow the vertical migration of their prey, cruising at depths of over 900m during the day before rising to within 100m of the surface at night. Much remains to be discovered about these remarkable giants and as yet we know nothing of their seasonal migrations, reproduction and development.

SAUROCETIDAE (Lizardwhales)[]

A sampling of saurocetids (with apep): 1. Prownose lizardwhale, 2. Apep, 3. Zahn, 4. Mosapoise, 5. Mosark, 6. Sawsnout lizardwhale, 7. Dusky lizardwhale, 8. Sakhala

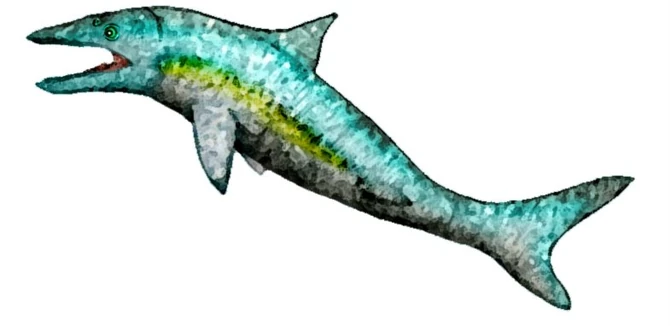

Along with the long extinct ichthyosaurs and the dolphins of Home-Earth, the lizardwhales have gained mastery of the oceans by convergently evolving (i.e.. ripping off) a shark-like body form. With their streamlined, fish-like contours, they are predators of extraordinary speed and grace that are a common sight in warm waters across the globe with twenty-nine extant species.

Saurocetids have long abandoned the sinuous swimming style that served the clade so well back in the Cretaceous. The swimming mode of a non-saurocetid mosasaur involves undulating either the long, muscular tail (the Hobb's leviathan) or the entire body aft of the forelimbs (the panlong), effectively undulating more than half of the total body length. The elongated body greatly limits speed due to the friction of water against the surface of the reptile. Lizardwhales, on the other hand, have the streamlined, fusiform body of a shark or nuclear submarine. Propulsion is achieved by undulating only the distal half of the tail (about one quarter of the total body length).

Comparative silhouettes of the Cretaceous mosasaur Tylosaurus and the extant saurocetid Saurocetus showing the radically differing body forms and the differing proportions of the animal that are used for propulsive undulation (black).

Although saurocetids do not display any sort of complex social interactions on the same level as marine mammals, they have surprisingly large brains for reptiles of their size. Lizardwhales lack the anal fins and lateral keels found in fast swimming fish and the large brain may be needed to handle this less stable swimming configuration. However, this reduced stability potentially makes a lizardwhale considerably more maneuverable than a comparably sized shark.

CARCHAROSAURINAE (Lizardwhales)[]

The saurocetid design has been a winning formula and the different lizardwhale species are little more than minor variations of this plan. However, clear distinctions within Saurocetidae do exist, particularly with regards to dentition. The carcharosaurines for example are powerfully-built predators equipped with numerous triangular teeth that bear prominent serrations. Some are truly enormous.

Zahn (Carcharosaurus atrox)[]

The zahn is one of the most fearsome lizardwhales. This 14 m long solitary predator can tear a fully grown mantasquid in half with a single bite. Zahns attack just about anything they can clamp their enormous jaws over, including seabirds, sharks, baleen squids, walducks, duckgongs, other lizardwhales, and inflatable boats filled with marine biologists. There have been at least two unfortunate incidents where Spec scientists have nearly ended up in a zahn's belly. However, they were apparently saved from the gruesome fate of being digested alive by the foul taste of the boat. After that, neither small inflatable dinghies or rubber boats haven't been used in zahn-infested waters.

Sakhala (Carcharosauroides velox)[]

At 3 meters long, the sakhala is one of the smaller carcharosaurines and patrols the outer reef faces of the tropical Pacific. It has a crepuscular hunting cycle, taking predatory reef fish as they themselves hunt in the dim light. In the daylight hours it can often be seen basking at the surface or descending upon the reef to take advantage of the cleaning services provided by small fish.

Mosark (Pristrix monstrum)[]

The Mosark is a 9 m long predator of warm-temperate oceans around the world. This species gained its common name from its shark-like appearance and behavior, and many of its relatives are also often unofficially referred to as mosarks for the same reason.

Chubby Mosark (Carcharosaurus crassus)[]

Warmed by the Gulf Stream, the waters off the coast of eastern North America are home to many predators, from walducks to sharks, but the most feared of all is the chubby mosark. These odd little mosasaurs dart around the shallows from Florida to Newfoundland, snatching up anything that moves.

Despite its common name, the chubby mosark is only distantly related to the true mosarks (Pristrix). These creatures, are, in fact, close kin to the zahns, massive, orca-like predators that hunt upper levels of the deep ocean. The 2 m long chubby, on the other hand, has become adapted for hunting in the nutrient-rich shallows of the continental shelves. These small hunters rely upon their sensitive Jacobson's organs to taste the water and home in on prey in the murky waters. As a result, the eyes of the chubby mosark are rather small, while their chemical sense is superb, even by lizardwhale standards.

The geographic range of the chubby extends further north than any other mosasaur. Although they winter in the warm waters off the coast of Florida, chubby mosasaurs spend the summer months rearing their pups in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. This behavior is useful, since the habitat is devoid of competing mosasaurs, and the native pods of selkies make a tasty snack for the larger reptiles. However, the northern water, although made bearable by the Gulf Stream, are still frigid to the cold-blooded mosasaurs, and so chubby mosarks must produce internal "coats" of insulating blubber, the source of their name.

Nodens (Nodens incredibilis)[]

As with Hobb's leviathan, the largest known lizardwhale was not first discovered in the sea, but on land. During the first years of spexploration, researchers came across a gargantuan rotting hulk that had been washed ashore. The 18-meter long carcass was easily recognized as a lizardwhale, but as the spexplorers lacked the appropriate equipment to transport that tonnage of meat, and the carcass was in such an advanced state of decomposition that further analysis was impossible to make at the time. The remains were hastily measured and photographed, and later some of the skeletal remains were retrieved. These fragments became the holotype specimen of Nodens incredibilis.

Later, several other Nodens skeletons were discovered, and the largest of these, consisting of little more than a skull measuring over 4 meters long, leads to an estimate of the adult size of some 20 meters long. It still took some time before the first verified eyewitness sighting of a living specimen, but through a lucky coincidence, a group of marine biologists happened to be near a Nodens mating area and managed to film the animals both above and under water. Although slightly shorter than the Hobb's leviathan, at over an estimated 60 metric tons, it is probably the most massive squamate to have ever existed.

The film revealed that the forequarters of the giant lizardwhales were covered in curious looking scars, some resembling those left by giant squid tentacles on sperm whales and others more unusual in appearance. It was deduced that the main diet of Nodens consisted of giant cephalopods, but the peculiar scars lead to some dispute over what had caused them. Some claimed the lesions were bitemarks of some kind, while others blamed that infamous cryptozoomorph, the great ktulu, which was reported as having feeding tentacles ending in hand-like extensions covered in wicked hooks. A photograph of a large Nodens individual with a severed end of a tentacle ending in just such fingerlike extensions still stuck on its skin only helped to fuel the controversy.

While the actual hunting and feeding of Nodens is yet to be observed, we do know that they are solitary most of the year and find their prey in the murky depths of the ocean teeming with myriads of exotic cephalopod species. These saurocetes seem to fill the niche of HE sperm whales, although we can only speculate at the differences in their hunting strategies. Despite having eyes not much larger than a human head, they are known to have a keen vision especially in the dark. It is worth noting that Nodens aismuch more likely to move close to the surface at night than during the day.

Dusky Lizardwhale (Naucratisaurus brenanae)[]

Despite being the heavyweight of the family, the dentition and biochemistry of the Nodens seem to link it with some of the most gracile and lightweight members of the group - the playful naucratisaurs. These are plesiomorphic carcharosaurines with slender bodies and a striking bluish-grey coloration that appears a brilliant blue underwater. They are also the only mosasaurs to regularly gather in large pods, up to several hundred strong, outside of the breeding season.

The largest and best known of these is the dusky lizard whale. Groups of these animals are commonly seen in the warm open waters of the Indo-Pacific. They hunt shoals of medium-sized fish and cephalopods in the sunlit surface waters, charging at their prey in a great uncoordinated rush.

Azure Lizardwhale (Naucratisaurus atlanticus)[]

The dusky's Atlantic cousin is the azure lizardwhale which doesn't get much larger than 4 meters. The bluish coloration is far more extensive in this species, leading to its common name. Huge pods are often seen congregating in the warm waters of the Gulf Stream.

Long-Tailed Lizardwhale (Naucratisaurus gracilis)[]

Long-tailed lizard-whales are a common species that form large schools off the western coast of North America. They feed on a variety of small fish and cephalopods.

Acrobat Lizardwhale (Megaucratisaurus saltator)[]

The 10-meter long acrobat lizard-whale is one of the largest of the lizard-whales. These long-lived creatures have been known to grow to 19 meters in length longer (though less massive) than Home-Earth's humpback whale. These are truly magnificent animals, particularly when engaging in water games, jumping fast and repeatedly often with other members of the familiar group behavior that has earned the acrobat lizard-whale its name. Often of a deep blue with some spots in the ventral area, the general color may vary among individuals, and the skin darkens greatly after death. Beached specimens are often found stranded on equatorial shores around the world.

Acrobats the big-game predators of Spec's seas, hunting the giant baleen-squid and dispatching their prey with powerful jaws lined with hundreds of conical teeth. Despite their ferocious dentition, these predators are not as aggressive as their smaller cousins, the zahns and actually seem to enjoy human contact.

These lizard-whales are not prolific and only will only reproduce once every three years. As with all saurocetaceans, acrobat lizard-whales are viviparous. Young are independent as soon as they are born, although acrobats will often gather into hunting pods when going after especially large baleen-squid.

Acrobat lizard-whales may be found in any of Spec's equatorial oceans, though their greatest population density is to be found in the Indian Ocean, where many individuals congregate to breed. Rather more intelligent than most lizard-whales, acrobats never lose a chance to jump out of the water and splash against the waves. Their courtship displays are likewise energetic.

SAUROCETINAES (Longnosed Lizardwhales)[]

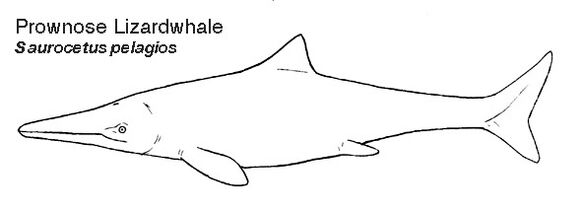

This distinctive subgroup of saurocetids are characterized by their narrow rostrums and lower jaws, giving them a distinctly ichthyosaur-like appearance. Their teeth are sparsely arranged unserrated pegs that are used for grabbing and squishing cephalopods.

Prownose Lizardwhale (Saurocetaceus pelagios)[]

The biggest long-nosed lizardwhale is the prownose that may weigh in at over 20 tonnes. It takes a wide variety of hard and soft cephalopod prey, including huge barrelfish.

Choo's Lizardwhale (Saurocetaceus brianchooi)[]

This cephalopod-hunting saurocetacean is restricted to a few remote insular shelves and seamounts in the tropical Indian Ocean with a total adult population of fewer than 3000 animals. Barely half the size of their cousin, the prownose, these animals greatly resemble the Mesozoic ichtyosaurs, which at first caused some confusion among the first explorers of Spec.

ODDBALL SAUROCETIDS[]

Mosapoise (Phocoenalacerta nigra)[]

Aside from the saw-toothed carcharosaurines and the narrow-nosed saurocetines, there are a number of unusual lizardwhales that fall into neither group and whose relationships remain unclear.

The mosapoise is a 3.5 meter long saurocete that specializes on hard-shelled benthic invertebrates that it crushes with its impressive battery of peg-like teeth. It is restricted to volcanic islands of the tropical Pacific where rich fields of bivalves grow on the igneous rock.

Devil Mosapoise (Diablophocoena megalodon)[]

While many saurocetids prey on ammonoids, the devil mosapoise is the true ammonoid-gourmand of the group, feeding on these cephalopods exclusively. With it's massive jaw and huge nutcracker teeth, this 2.4 m creature will attack ammonoids larger than itself.

Sawsnout Lizardwhale (Pristisaurus peculiaris)[]

The sawsnout lizardwhale is undoubtedly one of the weirdest of mosasaurs. Its upper jaw is disproportionally long and armed with sharp outwards-pointing teeth. Sawsnout lizardwhales use this weapon to stun fast-moving prey and to rake out buried prey from the bottom. It is one of the few saurocetes to inhabit inshore habitats, often foraging around mangroves and tidal channels from the Everglades to the mouth of the Amazon.

Common Indo-Pacific Moasapoise (Saurodelphis ubiquitus)[]

A newly discovered species of mosasaur, the common Indo-Pacific moasapoise can be found through out the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is one of the smallest species of mosasaur known to the world of Spec, growing no bigger than 6 feet long. Unlike most members of its kind with its slender body and slender jaws, it specializes in hunting the agile fish out in the vast blue of the Indo-Pacific Ocean.

Ribbontail Lizardwhale (Sauralopias tropica)[]

Sometimes placed in its own family, the bizarre ribbontail lizardwhale is immediately recognizable by the long, fleshy extension of the tail that makes up a third of its 7 metre length, the animal resembles a thresher shark in appearance but not in behavior. Skeletally, the caudal vertebrae are unremarkable, the "ribbon" being a boneless, floppy mass of skin and cancerous-looking flesh.

Due to the drag produced by its extraordinary tail, the ribbontail has a lower top speed than its relatives and can produce a defensive fecal cloud much like that of the Hobb's leviathan. The animal spends much of its time passively floating on its side out in the open ocean, less than 10 metres from the surface, where is drifts among fields of flotsam or large ammonoids. The tail is positioned to help maintain neutral buoyancy and perhaps to conceal its predatory silhouette.

Most importantly, it makes the ribbontail lizardwhale cast a very large shadow. Small fish take shelter in the mosasaur's shadow, just as they would with any other large piece of flotsam. The ribbontail tolerates these animals, very rarely succumbing to the urge to snap up one of its tenants. It needs these lodgers to act as bait and its large, dagger-like teeth clearly indicate a preference for more substantial prey.

In the oceans of both timelines, pelagic predatory fish regularly check up on floating garbage to see what morsels are hiding in the shadows. On Spec, they do so at their peril as such behaviour brings them within striking distance of the ribbontail which lunges at its victims with blinding speed. The shadow-lodgers feast on the debris of the attack and a number of small fish species have so far only been found in association with ribbontails.

,=Anguillacertidae=Anguillacerta sinensis (Panlong)

=Mosasauria=|

| ,=Archaeosaurocetacidae=Apep aegyptianus (Apep)

`=|

`=Saurocetacea

Brian Choo