INTRODUCTION[]

Oviraptorosaurs are a strange group of maniraptorans that made their début in the fossil record of Early Cretaceous Asia, if not earlier, as small... probable omnivores such as †Caudipteryx and continued through the Mesozoic and early Cenozoic as generalists/predators.

HISTORY[]

Oviraptors are some of the most bizarre groups of dinosaurs that have ever existed. Nestled among the diverse clade that is Maniraptora, they seemingly made their debut in the Lower Cretaceous, possibly earlier as turkey-sized generalist herbivores such as †Caudipteryx, animals perhaps similar to the earliest maniraptoran, only with half-beaks or teeth concentrated in the tip of the jaws. Flash forward to the late Cretaceous, and they diversified in Laurasia as bizarre toothless theropods, developing robust, often parrot-like beaks, while their skull developed a complex pneumatic composed of unique nasally-derived airways. Many species also developed impressive head crests, derived from the nasal bones, and most curiously some forms retained fangs positioned in the palate. With euornithe-style pygostyles and wrist articulations that allowed to bend the hand far more than any other known tetrapod, including birds, the exact lifestyle some of these Cretaceous oviraptors led is still mysterious, though they were almost certainly omnivores, with possibly a major leaning towards herbivory. Notably, oviraptors reversed the maniraptoran condition of the pubis, now facing forwards as with most theropods, for reasons poorly understood.

In Spec, oviraptors obviously kept going, but not without hiccups. In the Eocene, most of their diversity was seemingly lost, with the odd, parrot-beaked, crested Asian oviraptorids basically vanishing from the fossil record, leaving only the disappointingly un-casqued and un-fanged †Cuniculavis to be found on the Eocene of Mongolia, China, and Thailand. In North America, the crested, "duck-billed" elmisaurids managed to jump into South America alongside the troodontids, though they largely disappeared from their homeland. Smaller, †Avimimus-like smaller forms remained common, however, is the main Laurasian fowl-analogs. In the Oligocene, oviraptorans reappear triumphant, with vulgure-like oviraptorids being common in Asia and North America while gryphons diversified in South America, replacing most of the smaller abelisaurs as the dominant predators in the region. Although they would eventually face stiff competition (and eventually being outcompeted by) in the large to medium-sized predator niche with deinonychosaurs; most notably the hesperonychidae deinonychosaurs, who invaded South America from the north during the Pliocene. Meanwhile the small tryannosaurs, most notably those in the Nototyranninae family, thrived when they arrived as well and the smaller oviraptorid predators still face competition from those predators in the area.

In the Neogene, oviraptors positively thrived once again, when one radiation of the smaller fowl-like forms, Suinavoidia, exploded in diversity, growing larger in size and producing the iconic hogbirds, as well as the highly successful bantams. In South America, gryphons managed to survive the interchange surprisingly well, and some forms became semi-aquatic coastoal molluscivores. They are currently a rather successful group, ranging on all continents except Oceania and Antarctica, from partridge sized to the largest of the living non-therizinosaur maniraptors.

OVIRAPTORIDAE (Vulgures, Gollums, Noodlers, and Seedcrackers)[]

The “classic/true oviraptors”, oviraptorids are distinguished by their extensive nasal air-sac system, that pneumatics most of the upper area of the skull, and their crushing parrot-like jaws with a dicynodont-like lower jaw curvature. In the past, members of this clade beared large, highly pneumatic casques and strange palatine fangs, but Cenozoic forms as far back as the Eocene †Cuniculavis lack these, though a few extinct vulgures have redeveloped casques. Currently, oviraptorids are mostly represented in two clades: the vulturosaurines and neopsittacines.

VULTUROSAURINAE (Vulgures)[]

Unquestionably the most successful of the oviraptorosaur clades, vulgures are found across Eurasia, northern Africa, and North America. More heavily-built and catholic in diet than the deinonychosaurs, vulgures tackle a very wide range of food. These adaptable creatures have been known to eat fish, birds, carrion, grasses, tubers, fungi, insects, mammals – in short, anything organic that isn't outright poisonous. Most vulgures are small, no more than two metres in length, but a few species reach larger sizes.

Gollum (Noctivagus smeagol)[]

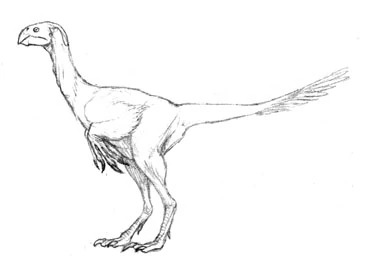

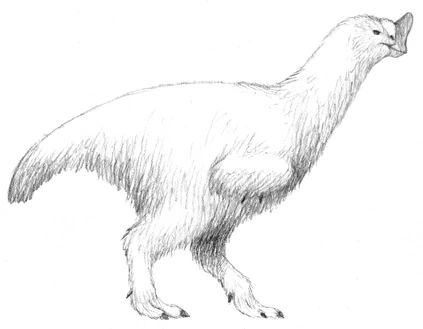

A small but very widespread vulgure, the gollum is a carnivore/scavenger of the forest. These little creatures range from Great Britain to Siberia, with related species spread across the Northern Hemisphere. Like most other vulgures, gollums are nocturnal, hunting at night and thereby avoiding direct competition with other small predators like harracks and bruisers. Probably because of the presence of bruisers across much of the gollums' preferred habitats, these little oviraptorosaurs are only indifferent scavengers. While gollums are as omnivorous as any other vulgure, they show a marked taste for fresh meat, which they can easily hunt with their sharp manual talons and ripping beaks. Gollums subsist mostly on a diet of mammals, birds, and fish, and also often raid the nests of other non-avian dinosaurs for eggs. Their calls have been known to sound horrible. Not eerie or terrifying, just plain horrible.

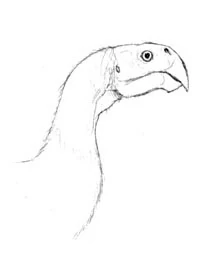

(fig. 1) Gollum, Noctivagus smeagol (Eurasia)

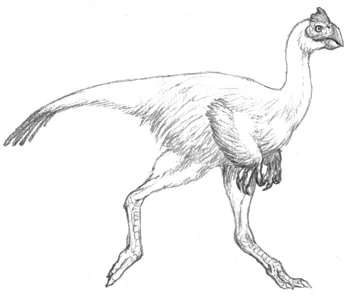

Despite being a close relative of the diminutive gollums, the grisly vulgure is one of the largest meat-eating maniraptorans of Eurasia. Though best known as a scavenger and a carrion-robber, its tendencies for carnivory aren't nearly as strong as one might assume based on its vulture- or harpy-like appearance. Vulgures are, in fact, closer in ecology to Home-Earth bears than to anything else, and the grisly vulgure is the aptly-named giant of the clade, a massive creature often exceeding four meters in length.

Grisly Vulgure (Vulturosaurus acerbus)[]

Grisly vulgures exist in many regional subspecies extending from Scandinavia and the Atlas Mountains to western North America. They do, in fact, kill and eat small animals, dinosaur chicks, and sometimes even fish. Most of their diet, however, consists of nuts, berries, roots, shoots, mushrooms and other herbaceous growth. Grislies are truly opportunistic omnivores, and often amongst the first dinosaurs to gather around the annual feast of the salmonite run.

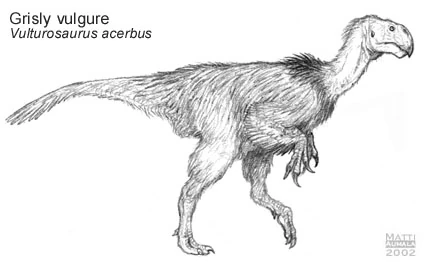

(fig. 2) Grisly vulgure, Vulturosaurus acerbus (Holarctic)

Because of their size (large females can exceed the length of 4 meters), grisly vulgures can usually rip apart any likely-looking food they happen to find, be it a honey-tree or a lammox carcass. The only predators to match or surpass grisly vulgures in size are barbaroraptors and tyrannosaurs, but the oviraptorosaurs will gang together to drive even a hungry drakhan or strider from a fresh kill.

When the female grisly comes into heat, she calls for potential mates with a ghastly howl, which can be heard many kilometers beyond the boundaries of her territory. These mating calls were known to spexplorers for many years before their source and meaning had been unraveled. This lead to the legend of the "boreal banshee", a name still occasionally used for the grisly vulgure itself.

Savannah Vulgure (Vulturosaurus africanus)[]

A related species to the Grisly Vulgure, the savanna vulgure (Vulturosaurus africanus), contributes to making the African savannas an unsafe but relatively clean place (though the crunchercrocs often reach a carcass faster).

The Old world tropics of Spec didn't keep out the dogbunnies or the metacanids. There is little surprise that a generalist African maniraptoran has eked out a living here. The Savannah Vulgure is a giant, at some 800 to 1,100 kilos. While they routinely scrounge up tubers, fruits, and grubs, they are more famous for scavenging. Unlike the Crunchercroc, which depends solely on their sense of smell, Savannah Vulgures will look to the skies to see circling gorgeese descend upon a carcass.

Savannah Vulgures raise chicks in polyamorous families. Chicks are fed a diet of scavenged meat, tubers and fruits during the dry season. Dry season rearing makes sense for these dinosaurs. They get most of their protein during this time, as well as fat carbohydrate-rich roots to dig up for water and nutrients. A subspecies are known as the Paleotropical Vulgure (Vulturosaurus africanus paleotropicalis) exist.

Indian Red Vulgure (Vulturosaurus ruber)[]

"Ugh" was the reaction of Spexplorers at seeing this beast from the open spaces of India and southwestern Asia. They have large reddish cornifications and pustules on the naked skin of their heads and necks. These 300 kilo beasts are honey thieves and devourers of fruits and succulent vines. However, they should not be regarded as gentle bens. Rashas will readily kill animals for food, provided they are easily dispatched.

Red Vulgure (Vulturosaurus americanus)[]

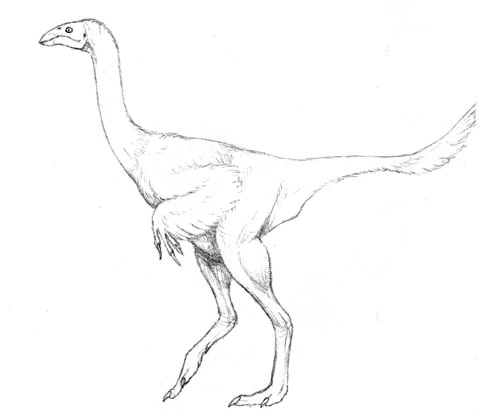

Due to its red-colored skin, the North American red vulgure (Vulturosaurus americanus) could almost be confused with the Indian red vulgure (V. ruber), which is a close relative of the savanna vulgure. However, the North American species must have split relatively early from the branch that led to the other vulgures, as shown by its retention of several "old-fashioned" anatomical features. Together with certain fossils, it suggests that the vulgure clade evolved in North America. Most North American red vulgures live farther south than any grisly vulgure; where the two species overlap, competition is nevertheless avoided, because the red vulgures are smaller.

(fig. 3) North American red vulgure, Vulturosaurus americanus (central and southern North America)

Noodler (Vulturosaurus floridensis)[]

The Noodler is an odd vulgure endemic to the Atlantic North American coastlines. Like the caenagnathid/elmisaur known as the Waldo, the Noodler has specialised in foraging in the shallows, developing a thick waterproof coat with insulating oils, though it has had much less time to evolve - it is estimated to have diverged from it's closest relatives in the onset of the last glaciation, and thus it's pretty much on the first steps towards a semi-aquatic lifestyle.

The Noodler occurs in many different coastline environments, from sandy beaches to rocky shores, but it prefers mostly estuaries and sheltered bays, and it is often also found deep inland in large rivers. It forages by mostly wading, dipping its head and claws to catch mollusks, crustaceans, seaweed, kelp, and occasionally fish. Still retaining the extensive pneumatic of most maniraptoanrs, when it swims it floats very easily, and only rarely does it dive. It can, however, be frequently seen dabbling like a giant duck, submerging its head and front body to reach underwater morsels. It will also forage frequently on carcasses of large marine animals, and will not hesitate to forage on land, feeding on sea bird chicks and small land animals or on berries and grass.

The current range of the Noodler extends along the temperate coastline of eastern North America, from the estuary of St. Lawrence River to the South Carolina shores. Subfossil remains show that it had a more southern range during the glaciations, with remains in the Bahamas and Florida, and presumably moved northwards in response to the Gulf Current.

NEOPSITTACINAE (Seedcrackers)[]

Seedcrackers are highly derived oviraptorosaurs whose cranial anatomy differs immensely from other species of the clade. In the seedcrackers, the beak has evolved to deal with hard seeds and nuts. This extreme specialisation has caused a de-pneumatization of the skull similar to that seen in the streks, but the seedcrackers are only distantly related to that relatively new branch of the oviraptorosaur tree. Seedcrackers probably evolved early in the Cenozoic, but the nature of their ancestors remains mysterious. Most palaeontologists ally them with the caenagnathids, making them cousins to the glucks, streks and vulgures, but others, pointing mostly to hand anatomy, place the otherwise long-extinct oviraptorids (like †Oviraptor itself) as the most likely ancestors of the seedcrackers. Still others place the roots of this clade even further back, finding links with the Early Cretaceous †Incisivosaurus. This hypothesis in particular,i s hotly contested, and only new fossils can shed light on the issue.

Crimson Seedcracker (Neopsittacus sanguineus)[]

Possessing excellent eyesight and an advanced sense of smell, the crimson seedcracker (Neopsittacus sanguineus) is a tiny species (25 cm in length), found only in the jungles of Southeast Asia. Male of the species sing a rich repertoire of melodies and are fiercely territorial, attacking any member of their species who sports more red plumage than they do. Female plumage is a drabber version of the males'.

(fig. 4) Crimson seedcracker, Neopsittacus sanguineus (southeast Asia); about natural size

Cenobite Seedcracker (Nucirepertor cenobitoides)[]

(fig. 5) Cenobite seedcracker, Nucirepertor cenobitoides (southeast Asia)

The cenobite seedcracker (Nucirepertor cenobitoides), arguably the most beautiful seedcracker species, lives in a bizarre, complicated symbiosis with the paintree and the nettletree throughout Southeast Asia. Reaching up to 1 m in total length, it is not as tiny as the crimson seedcracker, but still as small as expected for a ground-living seed- and fruit-eater.

CAENAGNATHIDAE/ELIMISAURIDAE (Waldos, Gryphons, and Baalous)[]

The dominant oviraptors in Cretaceous North America, caenagnathids/elmisaurs were rather odd animals, with wide, flat “duckbills” unlike the parrot-like jaws of oviraptorids - in the predatory gryphons, these developed profound blade-like serrations -, as well as a fused mandibular synthesis. With an arctometatarsal like that of ornithomimosaurs and troodonts, these animals are more adapted than other oviraptors for extensive running. Like Cretaceous oviraptorids, caenagnathids/elmisaurs also have large casques, and modern species retain them, albeit usually reduced ones.

In Spec, the caenagnathid/elmisaur entrance into the Cenozoic was mixed. On the one hand, the decline in their North American homeland, eventually disappearing in the Oligocene, but in the other, they managed to secure a place in South America. There, they were in a privileged position to expand and did so by not only taking niches in other places taken by vulgures and hogbirds, but by also becoming the dominant theropod predators of the continent, producing fearsome macro-predatory forms known as gryphons. The earliest gryphon known, †Eogriffos, appears as far back as the late Eocene of Argentina, when the local predatory noasaurids and carnotaurine abelisaurs still roamed, already exhibiting the robust arms and serrated raptorial beak. In the Oligocene, the older carnivores seemingly vanish, leaving only the fearsome oviraptors, some of which already over a ton in size, which would reign over South America for most of the Cenozoic.

Unfortunately, the gryphon reign in the neotropics was not eternal, and the Panama Interchange allowed the invasion of errotyrants/errosaurs, also cursorial predators but with actual teeth, which can be replaced in case of damage, unlike the beak serrations of the gryphons. Nowadays, the oviraptors remain as just sprinting cheetah (or Cain) like predators, though the omnivorous dire-rheas and the weird semi-aquatic Waldo still remain.

Waldo (Vulguropsis tardox)[]

The Waldo is pretty much the gryphon answer to HE's †Thalassocnus, albeit a molluscivore and not a herbivore, which might explain why it survived while the sloth died out. Fossils of Vulguropsis first show up in the late Miocene of Chile, and between the earliest fossils and the modern species, there is a line that seems to show a ladder between a fairly normal caenagnathid/elmisaur and the current result. The living Waldo, still occurring naturally in the cold waters of western South America, strongly resembles a giant, beaked torrent-raptor, with it's streamlined, dense feather coat, it's large webbed feet and the somewhat penguin flipper-like appearance of its wings. At three meters in length, this animal is rather robust for gryphon standards, having lost some of the pneumas of their fast ancestors, though still relying on gastroliths to lose its buoyancy. A rather slow swimmer, it prefers to wade in the sea bottom like an oviraptorian hippo, pulling mollusks and crustaceans with it's beak and claws. Nonetheless, it's capable of bursts of speed when endangered.

Waldos have several methods for processing prey. Smaller prey is often swallowed whole while underwater, with the gastroliths in the gizzard and strong stomach acid often enough to break through weak shells. With larger prey, particularly mollusks, Waldos return to shore and rely upon their "swiss army hands." Digit one has developed a laterally compressed but strong cla- like a curved letter opener, allowing Waldos to use their thumbs to pry shells open with one hand while the other grips. For especially large prey with heavy shells, Waldos will even utilize tools, placing the prey against a hammer stone while smashing it with a smaller stone. Lacking substantial wrist mobility, they are not as deft at this feat as a human would be, but they need not worry about their prey escaping, and make up for in raw power what they lack inaccuracy.

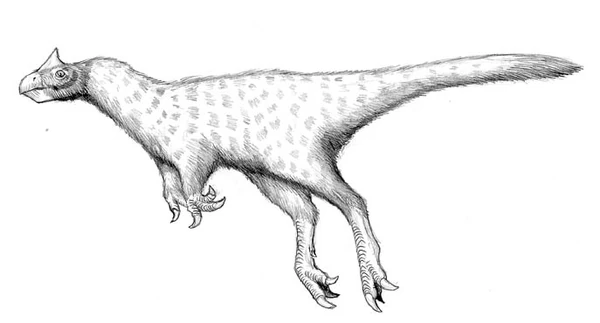

Royal Gryphon (Velocimanus major)[]

The Royal Gryphon pales in comparison to its extinct cousins but is a formidable and dangerous animal. It weighs up to 600 kilograms, with a head as large as a horse's. Unlike other oviraptorosaurs, it has full binocular vision, as befitting its status as a diurnal hunter. Although comparably rare, it can be found anywhere east of the Andes and south of the Amazon rainforest. It always hunts prey smaller than itself, generally preferring singers, immature pachamacs and torgs, and Glory Elk. However, in times of scarcity, it will hunt small prey such as viries, or nandrake. Gryphon hunts begin with a quick sprint which generally does not last longer than a few minutes. If a gryphon successfully closes the distance between itself and its prey, it then causes its prey to stumble using its forearm. Its arm is among the longest of carnivorous dinosaurs, culminating with a comparably short first digit (thumb) and elongated, yet stout, digits 2 and 3. Functional anatomy studies suggest the gryphon hand can take far greater stresses than normal for a maniraptoran hand due to extremely strong tendons. This gives the gryphon the option of not only using its arm as a passive tripping device as cheetahs do, but actively grabbing the leg of running prey if need be. Once its quarry is on the ground, it is quickly dispatched through a precision bite to the neck. The gryphon then eats quickly and messily - although a skilled hunter, it cannot defend its kills from errotyrants larger than itself.

Llanos Gryphon (Velocimanus minor)[]

The Llanos Gryphon appears to be descended from a population which became stranded north of the Amazon forest som time during the ice ages. It is much smaller than its southern cousin, generally topping out at 250kg. The bulk of its diet is made up of the Llanos Jackassalope and local spelks and viries.

Baalou (Ursovulgur hispidus)[]

The vulgure species native to India, the Baalou is a notoriously aggresive omnivore, weighing generally as much as other vulgure species. Its plumage is a dirty black and its beak is white. It occasionally, as an extra source of protein, will break termite mounds and gorge on their succulent pupae and piqaunt soldiers.

SUINAVOIDIA (Glucks and Hogbirds)[]

The by far most diverse clade of oviraptors, these animals evolved from ancestors akin to the Cretaceous †Avimimus, and are rather set apart from the other oviraptors. Unlike the parrot beaked oviraptorids and “duck-billed” caenagnathids/elmisaurs, suinavoids have basally rather simple beaks, being basically just toothless maniraptor jaws covered by rhamphothecae (if proportionally shorter and deeper than the average basal maniraptor jaws), though several species have naturally specialised their jaws. Their back vertebrae lack the pneumacy seen in other oviraptors, and the occipital condyle is comparatively smaller than in other oviraptors.

The earliest known suinavoids come from the Eocene of Pakistan, though the clade didn’t become particularly diverse until the Miocene, when it exploded in diversity. Now, they compose the bulk of oviraptor radiation, being still mostly focused in Eurasia and Africa, but with several species in North America as well.

SUINAVIIDAE (Glucks and Hogbirds)[]

Suinaviinae is an odd group of slender, long-legged caenagnathids with a predilection for foliage. These little animals much like Home-Earth pigs in their habits.

The fossil record of oviraptorosaurs in the Paleogene and Neogene is notoriously poor, but mitochondrial analysis indicates a wide gap between the vulturosaurines and the suinaviines + cervaviines (although these groups are more closely related to each other than to the weird neopsittacids). Based upon this data and some fossil fragments from Spec's Iranian Plateau, specbiologists believe that Suinaviinae and Vulturosaurinae parted ways in the Miocene. Since that time, the glucks and hogbirds have diversified further and now consist of several clades of omnivorous runners.

[]

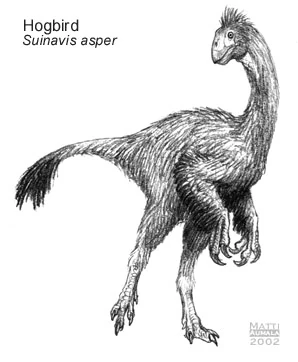

(fig. 6) Hogbird, Suinavis asper (western and northern Eurasia)

When specbiologists first observed a living Suinavis asper, they must have wondered if they were looking at a bird or a pig, since they immediately decided to name it the hogfowl. For reasons now forgotten, the name has since come to mean the British subspecies, and the common name of the Eurasia-wide occurring species has changed to hogbird. The basic implication of the name, however, remains the same.

This forest-dwelling Eurasian animal is indeed very much like wild boar on chicken legs, despite the external differences (and a couple of internal ones as well) and its somewhat larger size (up to 1.5 m in total length). Hogbirds are omnivorous, leaning towards herbivory. It is hard to think of anything edible hogbirds wouldn't at least attempt to swallow, and so it is no surprise that they are some of the most adaptable animals on the continent. Hogbirds are, however, limited to the temperate and subtropical zones.

The green-brown-black coloration of a hogbird's stiff, hair-like plumage blends into the background of the forest. The feathers on its back and neck are in fact quite stiff and prickly – though nowhere near as sharp as the quills of a manticorant. When you add to that the sharp claws on a hogbird's hands and feet, and of course its fearless and aggressive nature, one has to wonder why anything would want to try their luck with one of them. They are, however, among the principal prey of draks.

Jungle Hogbird (Choerornis silvester)[]

(fig. 7) Jungle hogbird, Choerornis silvester (central Africa)

The jungle hogbird (Choerornis silvester) of Africa's rainforests are close relatives of the hogbird. Up to 2 meters in length, these stocky animals like to scavenge and have been seen running after paraselenodonts, but normally they eat leaves, shoots and fallen fruits. Jungle hogbirds also use their strong arms to pull branches down, therizinosaur-style.

Gorillabird (Hapaloraptor robustus)[]

(fig. 8) Gorillabird, Hapaloraptor robustus (central Africa)

Deep in the green hell of Africa, there resides a big black beast with a green underside and green stripes on its legs. It seems to be exclusively herbivorous (unlike the black beast!), but fearsome tales are told of its enormous strength. Hard facts about the gorillabird (Hapaloraptor robustus), however, are hard to come by. Despite its small tail, it reaches a length of 6 m (not 8 as the first expedition claimed), and its well-guarded nests contain only 2 eggs the size of rugby balls. Preliminary investigations place this mighty oviraptorosaur next to the tiny seedcrackers, based mainly on its large, powerful head, its impressive beak, and limited genetic evidence. This result produces more riddles than it solves. Why are there big and small seedcrackers, but none of intermediate sizes? Did seedcrackers evolve in Asia or Africa? What does it need this extra-huge head for – are there some sort of coconuts in Spec's African rainforests? Even this is not yet known. Recently it was discovered that three species of gorillabird have been discovered.

Wabe Gorrillabird (Hapaloraptor robustus robustus)[]

The first subspecies and largest of the subspecies can be found the Congo Basin, browsing the plant life with the various cirafs in the area as well. These also seem to be the most agresgsive of the gorillabird species, troops are usually lead by a monarch male who will defend his troop with his life from any carnivores, most notably the jungle pantherbull in the area and the females are no better. Females will defend their chick to theth until they are able to defend themselves. Interestingly, the do to show any hostility towards our human explores.

Mountain Gorrilabird (Hapaloraptor robustus montanus)[]

The second and smallest subspecies of gorrillabird can be found roaming the in the mountains regions of Africa. Unlike their other species of gorillabird, these species beaks are more long and slender in order to devour the plant life in the areas traveling in family groups. Interestingly, their feather coloration seems to be vastly different from the traditional coloration from the gorillabirds, seeming to be more adapted to the mount'ains environment.

Bush Gorillabird (Hapaloraptor robustus giganteus) []

The third and final subspecies of gorillabird is the tallest of the subspecies can be only found in the Ugandan jungles. These creatures seem to be the rarest of the gorillabird species, it has been believed that these creatures are doomed to face extinction. While conservation efforts have taken, place some people seem to be skeptical about this issue. These creatures seem to be most docile of the gorillabirds, but they will defend their chicks from any potential threat who tries to dare attack them.

GALLOCEPHALINAE (Glucks and Nostriches)[]

This tropical clade of suinaviids are herbivores of forest margins and open plains. They have ostrich like breeding systems, the dominant female and male brooding up to 40 eggs from all lesser ranking glucks within the area. The majority of the brooded eggs that hatch will be the ranking couple’s, as most other eggs are rolled away from the nest or pushed to the edge. Interestingly enough, right before the chicks start pipping, the two parents will crack open and devour the contents of unhatched eggs. After the chicks have struggled out and dried off, their first meal is a liquefied stew of the failed eggs. This milk has properties similar to mammal colostreum, having great nutritional value, but also laced with immunization properties of both parents.

Red-Hat Gluck (Gallocephalus macdonaldi)[]

The red-hat gluck (Gallocephalus macdonaldi) is a typical gluck (Gallocephalini). Like all African glucks, the red-hat lacks a crest, but its neck skin is bare and brightly coloured in males, with a red wattle adding to the effect. The long pedal claws are used for digging up roots or burrowing animals (or inflict nasty wounds to anyone foolish enough to attack the animal from the front). Red-hat glucks can be found across the dry savannas of Africa.

(fig. 9) Red-hat gluck, Gallocephaus macdonaldi (subsaharan Africa)

Combed Gluck (Gallocephalus meleagrides)[]

Combed Glucks are denizens of the Great Karoo in Southern Africa. Their gigantic size at nearly 200 kilos is rather odd until one considers that the only scaly skinned African competitors are small burrowing jackalopes and aardcrocs. They are well adapted to the incredible weather extremes of this land, which may see temperatures swing from 30 Celsius to -5 Celsius at any time of the year. They browse the xerophytic vegetation during the crepuscular hours, preferring to shelter in dens during the hot day and freezing nights. Unusually among glucks, chicks are parented by monogamous pairs during the austral spring.

(fig. 10) Combed gluck, Gallocephalus meleagrides (Southern Africa)

Swarm Gluck (Gallocephalus geeireysia)[]

Also known as the Yellow-Faced Gluck, the Swarm Gluck is a slightly larger and much more social creature. Living in the scrub and grassland of Africa's eastern coast, Swarm Glucks congregate in troupes of over 50 to 100 individuals. Gluck social structure has attracted much attention from the scientific community, but observation has yielded little insight into the social structure of these oviraptorids.

Troupes are not lead by a single male or female, but, it seems, by the entire collection of adult individuals. When the troupe defends its territory or collectively gathers food, for example, no individual acts before any other. Rather, the entire adult population acts at the same time, each member of the troupe performing some part of the task at hand.

Certainly, these oviraptorids are capable of complex communication, and the accepted hypothesis concerning their coordinated behavior is that the glucks 'tell' each other what to do in certain circumstances, a mode of behavior that seems to be intriguingly close to human.

Efforts to translate the glucks' vocabulary of clicks and peeps have met with little success, and critics point out the small size of the glucks' brains relative to their body size. The hypothesis proposed to explain the glucks' complex behavior in the absence of intelligence is flocking, with each individual obeying its own simple set of instincts in relation to other members of the troupe. Computer simulations of gluck behavior seem to corroborate this 'dumb gluck' hypothesis, but most field researchers still maintain that "there's something going on in those heads…."

Nostritch (Pseudostruthio africanus)[]

It is easy to see why early spexplorers gave the nostritch (Pseudostruthio africanus) its name. Through convergent evolution, this taxon has come to closely resemble the ostriches of Home-Earth and the ornithomimids of both worlds, as well as the streks of Spec (see below). The nostritch is actually a large gluck, even though it hardly even looks oviraptorosaurian. Nostriches are fairly widespread across Africa on both sides of the Sahara, as well as in the Middle East. Fossils, however, indicate that these odd creatures evolved in the Eurasian steppe when it was warmer, around the Miocene-Pliocene boundary.

(fig. 12) Nostrich, Pseudostruthio africanus (Africa and Middle East)

ARIAVIINAE (Ramfowl and snowstrek)[]

During the Late Miocene, a clade closely related to Suinaviinae reached the cooler parts of North America. Largely pure herbivores, these dinosaurs have converged heavily upon the streks (see below) and were at first classified with them. Ariaviinae achieved a moderate but short-lived diversity in the Late Miocene and Early Pliocene, of which only [or not!] the ramfowl and the snowstrek remain.

Ramfowl (Ariavis montanus)[]

The 1.5 m long ramfowl (Ariavis montanus) is North America's answer to the mountain-streks. It lives in grassy areas in the Rocky Mountains. Males have wide and thick bone and keratin crests that function much the same way as mountain sheep horns: the males will bang their horny crests together to establish dominance.

(fig. 13) Ramfowl, Ariavis montana (North America – Rocky Mountains)

Snowstrek (Villopluma rostricornu)[]

Quite similar to a true strek except for its long feathers, the snowstrek (Villopluma rostricornu) is thought to have spread from the frigid mountains to the frigid plains in some ice age or other. Large herds of these 2 m long animals now roam the Arctotitan steppes that encircle the Arctic Ocean. This freezing habitat has led to certain specializations, such as the flat horn-like crest found in both sexes, which can be used to dig for food from under a thin cover of snow, and the enlargened nasal cavity that forms a very distinct bump on both sides of the head.

(fig. 14) Snowstrek, Villopluma rostricornu (Holarctic regions)

Mongolian Steppe Strek (Antilocapravis mongoliensis)[]

The largest living ariaviine, this 40 kilo folivore follows herds of spelks, segnosaurs, and catoblepines. They feed on exposed forbs and new growing grasses. They often raise chicks within the crèching grounds of larger herbivores. The alertness and high aggressiveness of the larger scythe clawed dinosaurs and sharp horned spelks and hadrosaurs deters almost all predators. The streks themselves will gang up and use their wickedly sharp for claws to deal with smaller predators such as possum dogs and vulpessaurs.

CERVAVIINAE (Streks and mountain-streks)[]

The Quaternary Glaciation profoundly altered the balance of the Northern Hemisphere's animal life, much more so than it did in our timeline. While Home-Earth, ruled by furry mammals, saw much extinction and rearrangement of species as the glaciers ground southward, these ecological perturbations pale in comparison to the massive upheavals of Spec's Late Pliocene and Pleistocene, as entire groups of large, scaly herbivores found themselves suddenly unsuited to their environment. Titanosaurs, Hadrosaurs, and Ceratopsians vanished from Europe, Asia north of the Himalayas, and most of North America in a geological eyeblink, and their replacement is a process that is still under way. therizinosaurs, of course, quickly placed themselves in all large herbivore niches in this vast area; some, the panhas and lemeks, even readapted to a running lifestyle. Some mammals, the specerotheres, started growing tremendously. But oviraptorosaurs participated in the run. Having just diverged from the glucks and hogbirds, the streks and mountain-streks quickly became the most diverse cursorial herbivores of the coniferous and mixed forests as well as the freezing mountain ranges of the Northern Hemisphere, keeping the mainly grass-eating ceronychids from becoming important leaf-eaters, and the specerotheres from growing to the sizes of Home-Earth's "ungulates" (if we ignore the caripoo which lives in the oviraptorosaur-free tundra).

Streks and mountain-streks are anatomically only a little different from their omnivorous cousins, and most of the changes are associated with a shift in diet toward strict herbivory. Their skulls are stronger than those of other caenagnathids and better capable of crushing woody plant material, the air-filled chambers that characterize the pneumatic heads of most maniraptors having been largely replaced by bone. The gut is expanded, forcing the pubes back, as in therizinosaurs and ornithscians. The hands are small, the fingers only weakly clawed, but the legs are long and powerful.

Gold-Crested Strek (Cervavis reconcilius)[]

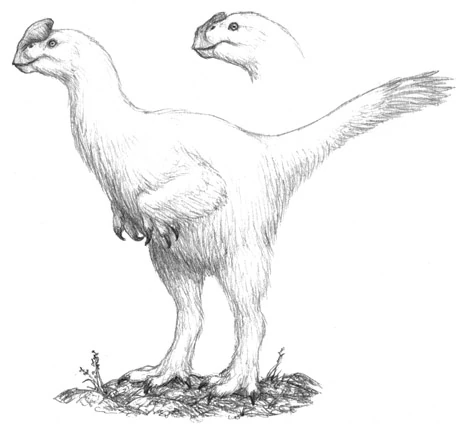

The gold-crested strek (Cervavis reconcilius) is one of the largest Eurasian streks, growing up to two meters tall. The male has a large yellow and black crest on his head, similar to the bony casque sported by the long-extinct †Oviraptor, the streks' distant relative. The gold-crested strek's crest is not bone, however, but keratin, an extension of the beak that runs backward along with the skull and flares up into a flag signaling the male's potency during the mating season, when it is used in ritual battles over the domination of harems of up to 20 females. The males' crests, along with the females' smaller, black knobs, also serve as protection against branches and thorns as the streks run through the forest, serving much the same function as a Home-Earth cassowary's casque.

(fig. 15) Male gold-crested strek, Cervavis reconcilius, and head of female (western and northern Eurasia

Majestic Strek (Cervavis regina)[]

The majestic strek (Cervavis regina) is by far the largest of the holarctic streks. Standing up to three meters tall and weighing more than half a ton, this animal seems like the oviraptorosaurs' answer to the bighorn claws. The comparison is not far from correct either, as it one of the few streks that actually spend the whole year in the boreal zone and can also be found in montane habitats in the spring and summer. Like all streks, the majestic still prefers more palatable foliage to conifer needles and is most often seen grazing grass, shrub,s and tree saplings. Using its arms mainly for brooding, it also lacks the strong arm muscles and formidable claws of segnosaur, and prefers to run instead of fight when threatened by predators.

The defining features of the majestic strek are its dark neck and tail (except for the whitetail fan), lack of a mottled pattern on the back, and the male's bright orange three-spiked casque, also referred to as the crown. The spikes of the crown grow and turn progressivelyredderd as the male grows older. The female has a small simple dark grey casque similar to that of the gold- crested strek. Males can sometimes grow twice as large as the females, which rarely exceed the weight of 300 kg, and despite the lack of segnosaur-like claws, it is far from helpless: one kick from its powerful legs can be lethal. Old males have also been seen causing grievous harm to predators with their spiked crowns, a behavior that has never been observed in intraspecific battles.

Johnny Deere (Elaphornis deerei)[]

Smaller and more lightly built than gold-crested strek, the johnny deere (Elaphornis deerei) is perhaps the most common strek. The casque of males of this species becomes bright green during mating time. The mountain-streks (Caprogallini) have settled in Eurasia's mountain ranges. They have developped shorter bodies and necks to save heat in their treeless environments. The vertebrae at the tail base are lengthened, producing a long balancing tail. Broadly comparable to the chamois, ibex and various mountain "goats" of our timeline, mountain streks run and jump much, but are also well suited for actual climbing thanks to their long, clawed toes and long, strong, mobile arms.

Gamsgan (Rupricapranser alpinus)[]

Gamsgans tend not to stray close to or above the snowline like honas and upclaws, but feed mainly on the tough mountain vegetation and other foodstuffs found along the craggy mountainsides. Due to the interesting details of their evolutionary history as a group, the species are fairly distanced from one another, due to their isolation in mountainous areas. From the typical base features of the Pliocene lowland members of the group similar features arose somewhat independently, like the longeclaws and the shorter neck. However, the fossil record and genetic testing show that all gamsgans are closely related; it is assumed that they migrated between Eurasia's largely near-contiguous mountain belts in the ice ages when the tundra-like conditions of the high mountains also ruled the plains.

(fig. 16) Male gamsgans, Rupricapranser alpinus, in mating season (Alps, Pyrenees, Apennines and Carpathians)

Himalaya Mountain-Strek (Caprogallus tibetanus)[]

(fig. 17) Male Himalaya mountain-strek, Caprogallus tibetanus, in mating season (Himalayas, Pamir, Hindukush, Tian Shan)

The Himalaya mountain-strek (Caprogallus tibetanus) has a much larger in-season breeding crest than the gamsgans. These creatures are rather flamboyant in their mating crests, males growing the largest keratinous headgear of any oviraptorosaurian, as well as large blue wattles. Their range extends from the Himalayas, Pamir, Hindu Kush to the mountains surrounding the Tian Shan. Hens have rather spare clutches, often just 4 to 6 chicks in hidden bluffs.

Oak Bantam (Tetronareptilius quercus)[]

Oak Bantams live fast, furious lives. They breed from late winter into early fall, with most individuals rarely living to see their third natal seasons. These 1 kilo grouse like critters either scurry for food in leaf litter or soft inner bark wood, trot around in the snow during winter months to nip at buds and winter fruits, or use their powerful wings to WAIR their way into tall trees, obviously favourinf oaks, feeding on their bark and acorns. Their range extends from the British Isles as far east as the Black Sea shores.

Bog Bantam (Tetronareptilius sphagnum)[]

A denizen of the European "low countries", which in Spec, are vast areas of complex marshy estuaries. This bantam is unique for feeding on bog plants, including the main staple, mosses. Their toes are much longer than is typical, although nowhere as freakish as HE lily-trotters. They are cryptically colored, with shades of black and brown, giving off a slight green iridescence. Nests are brooded within reeds, often floating. The chicks are hatched within 20 days and are quite precocial, following their parents, pecking for foliage and insects along the way.

Conifer Bantam (Niveatetronareptilius pinus)[]

Conifer Bantams can be found throughout Eurasia from the Baltic peninsula as far as Kamchatka. Many closely related species can be found in pockets along the Eurasian mountain chains. These little chook-ike dinosaurs forage for low growing conifer needles as well as browsing forbs and snapping up the abundant insects of summer. Winter has them stripping buds, raiding hibernating mammal stores ,and even scavenging from carcasses.

Prairie Bantam (Poagallosaurus poagallosaurus)[]

Bantams have had great success on the cold steppes and prairies of Spec. Indeed, it is believed they have achieved their greatest numbers here, both in terms of species and total biomass. The Prarie Bantam of the Rocky Mountain Front is a typical member of the genus. These 50 gram critters raise chicks within harems of one to two males and up to eight females. The winter season often has them following resident spelks and segnos. They dash into peck scraps the much larger animals miss when they scrape away snow.

Palanquin (Cervavis palanquin)[]

Palanquins are 10 kilo sized browsers of the Eurasian deciduous forest found as far west as Siberia and as far south as subtropical China. They retain spotted coats like their larger relatives, but also have a whitened underbelly. Roosters develop a "shine" during the breeding season that attracts females. Unfortunately, it also attracts predators as well. The male who can display and yet remain obscure to predators through certain tricks is the most desirable in the leks. Harems of up to ten females with their accompanying clutches are their most fervent protectorate. Recent work has shown they are part of a ring complex numbering some 6 species and varying subspecies throughout Eurasia.

Chelken (Cervavis alcavis)[]

The Chelken is the most aquatically inclined of the streks. Found throughout the boreal Holarctic, they wade and dabble in ponds and river shores for aquatic plants. Indeed, nests are often constructed within reed beds early in the spring. The 20-kilo male proudly defends his hen from intruders, often luring enemies as large as saber tyrants away from the next generation. The cold season sees the half grown chicks follow their parents into the multi-species winter yards. By their 2nd year, the young chicks are debating whether to leave their parents and set up territories of their own, staying the longest with the parents out of all bantams.

Tierbird (Cervavis germanicus)[]

This strek is ubiquitous throughout Europe, as far as the Urals and the Caucasus. Tierbirds are roughly 36 to 40 kilos in weight, making them one of the largest streks. They are extremely adaptable and common, found in open spaces and the deepest 100 meter oak woods. They often follow mixed association with spelks, brutons, and hogbirds. Brutons rip down aged trees, spelks devour the unpalatable fungi and fibrous plants. The hogbirds rip apart the rest. Tierbirds will begin plucking the new tender growth within weeks. East of the Urals, closely related species pick up the same behavior in both the deciduous and coniferous forests.

Ultra-Violet Tail (Neocervavis violaceocauda)[]

A strek endemic to North America's temperate forests, it is notable due to it's jet-black tail feathers. They actually reflect ultra-violet light, producing a rather garish display in UV. When threatened, the animal spreads it's black tail feathers, forming a visible sign that alerts other streks, allowing most of the flock to WAIR their way into safety on tall tree branches, or simply run away. Other animals, like multies, have learned to observe the UV Tails, reacting to their danger signals accordingly.

Tatanka (Tatankavis hahei)[]

And endemic to the Great Prairies, the Tatanka competes with the Tierbird for the title of the largest bantam. These streks engage in an interesting mating ritual. Both the males and females hold up their barred forked tail feathers beyond their casques. Circling each other, with deep lion like roars, each prospective mate challenges the other. Seeing a Tatanka display is subtly ecstatic, their pygostyles exactly matching the incipiently divided casques as they circle each other, using the backdrop of the dawning or setting sun to best demonstrate their coordination. Rhythmic, bouncing, swaying from leg to leg, the forked, feathered pygostyle giving the illusion of a horned head the entire time. Eventually, mature animals pair off and retreat to galley forests or extensive ridge tree stands to brood in late winter. Chicks are fiercely guarded, but predators still take quite a toll. Tatankas are quite common along the forested rivers of the Midwest as far north as Canada south to Mexico. / It is quite interesting that very little intra-gender competition occurs among these streks. Perhaps the huge stresses of clutching require both females and males to directly face each other off. Indeed, it is impossible to visually tell the sexes apart. Unlike the sheltered forest environs or highlands of most streks, Tatankas must expose their chicks to a wild and wooly world of extremely dangerous predators in exposed grasslands.

Daniel Bensen, Tiina Aumala, João Boto, Timothy Morris and David Marjanović

,=Noctivagus smeagol (Gollum)

|

,=Vuturosaurinae=| ,=V. acerbus (Grisly vulgure)

| | ,=|

| | | | ,=V. ruber (Indian red vulgure)

| `=Vulturosaurus=| `=|

| | `=V. africanus (Savanna vulgure)

| |

| `=V. americanus (American red vulgure)

|

| ,=G. mcdonaldi (Red-hat gluck)

,=Caenagnathidae=| ,=Gallocephalus=|

| | ,=Gallocephalini=| `=G. meleagrides (Combed gluck)

| | | |

| | ,=Suivaviinae=| `=Pseudostruthio altus (Nostritch)

| | | |

| | | | ,=Suinavis asper (Hogbird)

| | | `=Suinaviini=|

| | ,=| `=Choerornis silvester (Greater jungle hogbird)

| | | |

| | | `=Ariaviinae=Ariavis montana (Ramfowl)

| `=|

| |

| | ,=Ceravis reconcilius (Gold-crestted strek)

| | ,=Cervaviini=|

=Oviraptorosauria=| | | `=Elaphornis deerei (Johnny deere)

| `=Cervaviinae=|

| | ,=Rupricapranser alpinus (Gamsgans)

| | ,=|

| | | `=Caprogallus tibetanus(Himalaya mountain-strek)

| `=Caprogallini=|

| `=Villopluma rostricornu (Snowstrek)

|

|=Oviraptoridae=Oviraptor

|

|=Caudipteryx

|

|=Incisivosaurus

|

| ,=?Hapaloraptor robustus (Gorillabird)

`=?Neopsittacidae=|

| ,=N. sanguineus (Crimson seedcracker)

`=Nuciraptor=|

`=N. cenobitoides (Cenobite seedcracker)