Outwardly, viriosaurs closely resemble such Late Cretaceous basal neornithischians as Thescelosaurus, with small, birdlike heads atop long necks, long tails, and (generally) a bipedal stance. This resemblance to familiar ornithopods and certain other neornithischians is quite misleading, however. In their 66 million years of evolution, the viriosaurs' internal anatomy has gone through some changes.

Most of the features that distinguish clade Viriosauria from their basal ornithopod ancestors are cranial. Unlike the hypsilophodonts of the Cretaceous, the viriosaurs lack teeth on the premaxilla, bearing an iguanodont-like battery of beak and ridged, grinding cheek teeth. The premaxilla, itself, is large and fused with the nasal to produce a large, broad bone (called the "facial") that is often expanded into knobby display structure. In addition to these cranial features, viriosaurs are also generally possessed of an enlarged middle toe that gives these little herbivores a splay-footed appearance. These claws are probably a primitive shared feature of the entire clade, although several lineages have lost them.

Viriosaurs are most common in their homeland of South America, but have made significant inroads into North America in the wake of the Great American Interchange. For the most part, these dinosaurs occupy small herbivore niches, and are most common in forests. The clade has produced some larger, grazing forms, but most of these were driven to extinction by the hadrosaur torgs.

VIRIOSAURIDAE (Viries)[]

Most viriosaurs fall into this family of small, bipedal herbivores. All viriosaurids have four-fingered hands (although digits I and IV are often reduced) and the enlarged inner toe. Viriosauridae is a long-lived clade, with fossil representatives as old as 20 million years.

Spectacled Viri (Viriosaurus ("Marasaurus") sinkkoneni )[]

The spectacled viri is a common lower-story browser in the forests and jungles of central South America. The largest species in genus Viriosaurus (1.5 meters long in adult females), the spectacled viri is most at home in the cooler cloud forests nestled within the Andes. These little browsers can often be seen along the forest margins at dusk, when the males venture onto the pampas to call for prospective mates.

Lesser Western Viri (Viriosaurus occidentalis)[]

Viriosaurs spread rapidly northwards during the Pliocene, as the Panama landbridge became firmer. They are now the principal small herbivores of most of southern and central North America, but these warm-adapted ornithopods cannot diversify much beyond the snow belt.

In the valleys of the Sierra Navada mountains lives the lesser western viri. These viriosaurs vary greatly over their range (pictured here is a male of the Stanislaus subspecies) but all are rather small (no longer than two meters), with long legs and necks and short, robust beaks for cropping tough vegetation.

They travel in small flocks of roughly 6 to 20 adult animals and accompanying offspring. Unlike most other viries, the whole flock raises young together in communal burrows often taken over from bastardsloths or large herbivorous reptiles. The young are not forced out of their natal group for nearly a year, much longer than any other viri.

Adults of both sexes may reach nearly 1.5 meters and some 12 kilos, placing them among the largest of the viriosaurids. Their long legs allow them to cover ground quickly with little effort. The long necks and short, robust beaks for cropping tough vegetation are instrumental to ripping open watery cactus and snipping off pithy branches. Their long legs allow them to cover ground quickly with little effort. Often feeding on cactus, these viriosaurs have rather thick lips and tongues, reminiscent of those of HE giraffes.

Song's Viri (Viriosaurus songi)[]

Found through out Central and western North America, Song's viri is a particularly small, lively creature with a high pitched call. These creatures eat tubers and low-growing plants and have been reliably reported to dine upon grubs and other invertebrates. These viries are common during the spring or summer, but become much rarer during the winter. Whether this species hibernates or simply migrates is unknown. Song's viri is a particularly small, lively creature with a high pitched call. These creatures eat tubers and low-growing plants and have been reliably reported to dine upon grubs and other invertebrates.

Song's viri is a particularly small, lively creature with a high pitched call. These creatures eat tubers and low-growing plants and have been reliably reported to dine upon grubs and other invertebrates. These viries are common during the spring or summer, but become much rarer during the winter. Whether this species hibernates or simply migrates is unknown.

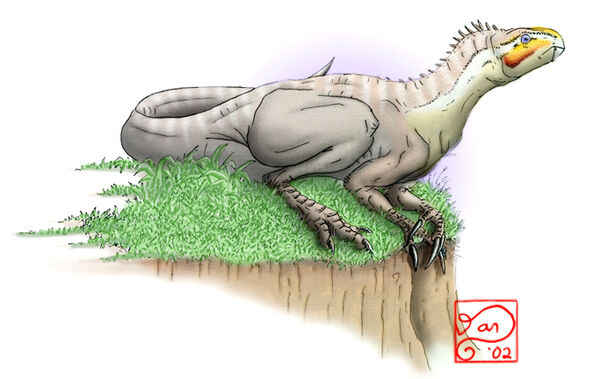

Yellow-Headed Viri (Sylvapascis vulgaris)[]

The yellow-headed viri is a deep-forest browser common in forests all over central and western North America. Yellow-heads are selective feeders and dart their heads in and out of the underbrush, searching for the tastiest bits of foliage.

They are highly specialized as selective browsers, pushing their heads into bushes for buds and new growth. These skittish 1 meter foragers dash into the safety of the deep woods whenever they are threatened.

KRANILIDAE (Cranili, Riparisaurs and Rooters)[]

Ranging from only a meter in length to nearly four, these marsh-loving herbivores are common in the warmer, wetter parts of South and Central America. Their bodies are generally robust, with powerful hind legs, and very small, four-fingered forelimbs. The neck is long and muscular, anchored by a series of enlarged neural spines over the shoulders. In the larger species, the inner toe-claw is often reduced.

As one travels south across the Americas, one notes an obvious change in fauna from the Eurasian therizinosaurs to the neohadrosaurs, and finally to these viriosaurs, bipedal ornithopods that have migrated from South America. Thus, while the bogs of Canada harbor tirgs, the swamps of warmer America are home to sludgers, the bayous of southern and Central America are the domain of the cranili.

Riparisaur (Riparisaurus amazoniensis)[]

Riparisaurs are very common small herbivores of the Amazon rainforest. These little creatures weave and dodge through the trees, feeding upon vegetable detritus and avoiding the watchful eyes of the jagulars and ocelotars. Their genus name is a bit of a misnomer, since they can be found throughout the entire Amazon basin from open fields and riverbanks into the deepest forests far from any large sources of water. These are the smallest of the viriosaurs, just 6 to 8 kilos and barely making a meter in length.

Cranil (Kranilis russelae)[]

The common (or striped) cranil ranges across Central America, with vagrants relatively common in the brackish swamps of southern North America. Cranili eat a variety of riperine vegetation and (during times of drought) will venture from the water to strip small trees of their leaves.

Pantanal Cranil (Kranilis paraguayiensis)[]

This is the largest of the viriosaurs, at nearly 270 kilos in aged individuals. Pantanal cranili are limited to this vast marshland. Herds hundreds strong forage for reeds, tubers and fruits along the riverbanks. Migrations may occur when too many juveniles are successfully raised. The older animals will push them out of their natural ranges, where they are heavily predated upon.

Bulls develop a dark purple blush to their bills during the breeding season. They may mate with one or two cows before all retreat onto an isolated sandbar surrounded by very deep waters to construct their nests. During this period, the expectant parents are very aggressive, having been known to severely injure or drown even large errotyrants or gryphons by swimming out to meet them. The unfortunate predators are no match for the massed and quick cranili who will push down on their torsos and safely hold down the thrashing head until the predator struggles no more.

Rooter (Javalinoides robustus)[]

Some North American kranilids (genus Javalinoides) have abandoned the water-loving lifestyle of their ancestors and have colonized the arid American Southwest. The rooter (Javalinoides robustus ) is a 2-meter-long, heavily built viriosaur that inhabits the dry grasslands of the Great Valley, where the Rockies split into two mountain ranges (the Coastal Range and the Sierra Nevada, leaving a long track of flat land in between. Rooters feed on the roots of the plants growing in the Valley, and tend to congregate around rivers.

LEVIPODIDAE (Laventadores)[]

Endemic to South America, the levantadores are the last remnants of an archaic radiation of giant viriosaurs that achieved some successes during the Oligocene and Miocene. Extinct levipodids are thought to have grown to lengths of nine meters, but no modern species is longer than six.

Levantador (Levipodus philogramis)[]

These viriosaurs are grazers, picking through the pampas for tubers and weeds, leaving the bulk of the grass to torgs. Most species have long, horse-like snouts, with broad facial bones, allowing them to graze while keeping their eyes above the grass, watching for predators. Levantadores possess only three fingers, and their inner toe bears a normal-sized claw. Many of the larger levipodids are quadrupeds, spending most of their time on four legs.

At 6 meters in length, the levantadores are the largest viriosaurs on the South American pampas. Grazing on all fours, levantadores will rear up on their hind legs to escape predators. This transition between bipedal and quadrupedal plant eater has happened a number of times in dinosaurian evolutionary history, and the levantadores are thus quite reminiscent of the much more primitive Lesothosaurus of the Jurassic.

The levantador seems to have been an early Pliocene grazer of the Patagonian pampas. Today, no ornithischian is found within a thousand miles of the site the levantadors have been recovered from, as it is much too cold. However, the early Pliocene was a warm period of sorts, and the southern pampas were more akin to northern Texas than to the chill windswept icebox of today. Large herds of levantadors migrated every spring southwards to feast on the rich grasses.

Levantino (Levipodus sinkkoneni)[]

The levantino was the smallest of the levantadores. A mature adult rarely reached over 3 meters and usually never more than 180 kilos. The levantino was not a migrant like its larger cousins, preferring to remain in the warmer north all year round. Ichnite tracks along a Pliocene lakeshore near Buenos Aires show two adults herding several young chicks. The tracks match levantino feet near perfectly, indicating they made them. This is an interesting development, since levantinos are never found in monotypic bone beds like most of their larger cousins. Perhaps the species was seasonally or permanently monogamous.

KENTROPODIDAE (Kentropods)[]

Kentropods are the most highly derived and unusual of the viriosaurs. With the exception of Dracorhea, the kentropods are small omnivores and insectivores, mostly of thickly forested areas.

Kentropods are immediately recognizable from other viriosaurs in have 3-fingered hands that bear large curved claws that are also present on the feet.

Hookjaw Kentropod (Kentropus therizinorhynchos)[]

This 2 metre long species is common on the rainforest floor as well as the large tracts of degraded land created by pseudosauropod herds. The hookjaw kentropod is immediately recognisable by its greatly expanded, spike-like predentary. It is perhaps the most predatory of the kentropods, but still takes fruit and some leaves. It hunts mammals and small reptiles, often using it's claws and uniquely adapted beak to pry open rotting wood to expose prey or to impale them in their burrows.

Caribbean Winklecracker (Klinebergella carcinovorax)[]

The Caribbean winklecracker (Klinebergella carcinovorax) is the northernmost-dwelling of the kentropod species and also the smallest, seldom exceeding a meter in length. This species is common along the Caribbean and Yucatan coastlines of South American.

The winklecracker hunts along beaches, and at low tide out onto the reef flats, for the marine bivalves and snails that form most of its diet (although the species has been observed to eat fruit, and will frequently take any crabs it discovers whilst hunting).

The head of a Caribbean winklecracker, Klinebergella carcinovorax

The winklecracker is, in all aspects of its anatomy, a beach-comber. The wrists of kentropod viriosaurs (as opposed to those of maniraptors) are flexible enough that the winklecracker can dig, turn small coral boulders and debris, and handle prey - certainly a useful adaptation in the winklecracker's unique niche. Shells and flesh are gripped between four tusks (convergently similar to those of the Australian rhyncoraptors) then crushed by the powerful flattened beak and swallowed.

This combination of kentropod and general dinosaurian features - beak, hands, and gizzard - has enabled the winklecracker to occupy a niche no animal in Home-Earth has colonized - that of a large shore-dwelling molluscivore. Home-Earth shorebirds, for example, would not be capable of bearing the extra weight of shell and still be able to fly efficiently, and other species lack the crushing beak, and digging adaptations, that make a diet of large shelled mollusks possible.

A Caribbean winklecracker foraging along the shoreline, using its powerful arms and long claws to overturn rocks in search of food.

Dracorhea (Dracorhea gracilis)[]

Despite its common name, the largest of the kentropods is probably more closely analogous to our world's Neotropical camelids rather than the rheas. It dwells in arid montane areas along the length of the Andes but also occurs at sea level in Tierra del Fuego. Dracorheas move in small herds made up of one male and up to a dozen females and their young. They are skittish animals that will flee at great speed at the slightest hint of danger.

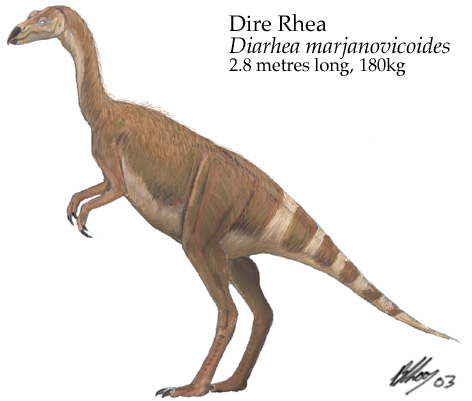

Dire Rhea (Diarhea marjanovicoides)[]

The awe-inspiring expanse of the South American grasslands plays host to a wide range of deadly animals, the majority of which are theropod dinosaurs. However, there is one very different kind of killer on the pampas that can pose a dreadful risk to the human spexplorer. For this endless golden vista is the domain of the dire rhea, a notoriously bad-tempered and exceedingly unpleasant kentropod viriosaur. Although commonly associated with the grasslands, this adaptable ornithopod can be found in a variety of habitats including Antarctic beech-forest, semi-desert and rocky shores.The dire rhea is an impressive animal that stands taller than a man. It bears a certain similarity to the unrelated Old World vulgures, which fill a broadly similar niche on the African savannah. Like other kentropods, they are formidably armed with wicked claws and are fast runners. It shares the erectile filamentous scales of its highland cousin, the dracorhea. These are highly developed in Patagonian animals, helping them to keep warm during the bitterly cold winters.

Dire rheas are highly omnivorous and will eat just about anything with a veneer of nutritional value. Small vertebrates such as mammals and lizards seem to be their favoured repast but they will also gobble down eggs, insects, leaves, seeds and fruit. They are efficient carrion-feeders, aggressively driving off other scavengers and using the narrow heads to probe the carcass for hard-to-reach bits of flesh. They appear to be quite intelligent and innovative, sometimes burying food in caches for future consumption. Dires on the Patagonian coast will wade into the shallows to pluck gastropods off kelp fronds or winkle for crabs. Those on the plains often follow large herbivores, both to snatch up small animals disturbed by their passing as well as rummaging through their dung for insects and undigested seeds. Although not primarily predaceous, they can easily dispatch a human-sized animal if the opportunity presents itself.

Adult dire rheas usually exist in mated pairs, the sexes are similar. Their way of life changes drastically as the year progresses. During the drier months, they are highly nomadic, roaming far and wide in search of suitable food, sometimes gathering in large feeding congregations around a carcass or watering hole. With the onset of the rains, breeding pairs of dire rheas soon adopt a sedentary lifestyle, staking out a nesting territory of between 100-200 square metres, usually near a reliable water source. As permanent freshwater is at a premium in many parts of the southern Neotropics, competition for prime nesting-territories is understandably intense and violent.

Both animals consume a far greater quantity of water than is needed for their survival during this period. Although, like other archosaurs, dire rheas do not urinate, the surplus water quickly passes through their excretory system, maintaining it’s clear liquid state. At the same time, a dietary increase in fruits and pond algae soon makes their feces exceptionally runny. Water and feces meet and are churned together in an enlarged colon where it is mixed with glandular secretions, the end result being a foul, odorous greenish-brown fluid. The raw stench of this liquid or “poojuice” is overpoweringly strong and is akin to rove-beetle spray combined with a very stale Indian curry plus doggie droppings.

Spring is in the air by a small lake on Chiloe Island as a pair of dire rheas mark their territory and reinforce their pair-bond with a charming nuptial ritual. After consuming mass-quantities of water, the ornithopods prance about their turf together, cawing loudly as they spray poojuice on everything in sight with breathtaking synchronicity. The noise of their cries (and flatulance) along with the stench of their sprayings give ample warning to any other dire pairs in the area that this stretch of lakeshore is occupied.

Only a minority of pairs produce luminescent poojuice as the bacteria only thrive in areas with constant moisture and a relatively mild temperature (such as on this lakeshore). However, those that do enjoy a significantly higher success rate in raising their offspring and as a result, these sites are much sought after and fiercely contested. Precisely what kind of advantage is brought about by glowing poo is a mystery. Perhaps the light attracts insects that have a similarly luminescent breeding display, providing additional food for the juveniles. Alternatively, as the substance readily clings to anything that touches it, it creates a deterrent to predators for whom glowing green and stinking to high heaven would be a severe handicap to successful hunting.

A picture of the same stretch of lakeshore, taken several days later at twilight, reveals one of the most haunting sights on Spec - the ground lit up by glowing trails of dire rhea poojuice. The green glow is caused by luminescent bacteria whose spores were ingested with the lake water. A glandular secretion mixed in with the poojuice causes these bacteria to flourish once expelled, creating this vivid display of light.

Pairs of dire rheas become exceedingly aggressive and combative during this time, even more so once they begin nesting, and will attack anything they perceive as a threat to their offspring. They will maliciously coat intruders with their noxious excretions, following up with a vicious flurry of pecks and kicks to those that fail to take the hint. Even magnoraptors, pachas and stormriders have been known to be subjected to this treatment although the kentropods are not suicidal and will retreat if a large, dangerous opponent appears unswayed by the initial spray-attack.

While getting sprayed in the line of field-research is not uncommon, several spexplorers have sustained serious and sometimes fatal injuries when venturing too close to a dire nest. There can be few deaths on Spec more stomach-curdling than a prolonged and agonizing (not to mention messy and noisesome) attack of the dreaded dire rhea! This is made especially frightening when out in the field, where one is naturally deprived of the facilities that one would normally seek out during such a biological emergency.

Spineback Kentropod[]

Known only from eyewitness accounts, the spineback kentropod is probably a kentropodid, but its affiliations within this family are unknown.

The 1.2 meter long spineback kentropod is rare species only known from a few specimens and photographs that dwells in dense tropical upland rainforest. It is an insectivore of the forest floor, apparently using its beak and elongated claws to search for food amongst leaf litter or to winkle bark beetles out of fallen logs.

Despite their formidable appearance, the row of quill-like scales along the back are actually quite soft and pliable.