"Pulling itself over the crest of a hill was a huge, dark form."

The Keeled Grove-back is a huge, primarily nocturnal, almost turtle-like tripedalien from the plains of Darwin IV. It was first discovered late one night during the First Darwinian Expedition in the Sinus Columbus, after Dr. Vinogradov, one of the Expedition's human geologists, detected a seismic disturbance from these immense creatures. They can produce roaring exhalation sounds. Because Barlowe was nearer the moving "epicenter," some seven kilometers distant, he asked him, very politely, to investigate it. He claimed that the tremors were local and steadily moving toward Barlowe. In Vinogradov's opinion, this intimated a non-geological origin and possibly zoological source. He apologized again for waking Barlowe, asked him to keep him informed, and signed off. The geologist's conclusions were correct.

The first sign of an approaching grove-back is not just from ground-shaking tremors, but also from the appearance of more than one arrowtongue (as well as other predator species on occasion), darting through the moonslit (if it is nighttime) undergrowth. In the distance is a faint scraping. It is a low sound, but growing against the background of slow, ground-trembling thuds.

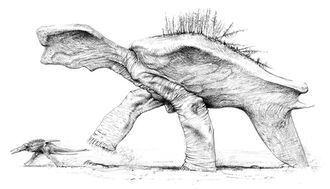

This gigantic creature is wedge-shaped, bio-lights always aglow at night, supported on two thick, pillar-like legs. It is estimated to be at least 60 meters tall.

At times, following arrowtongues can be caught under the larger animal's skid that makes up the rear of its body. The predator will be crushed like a grape and passes over without the slightest notice from the looming giant.

A newly-emerged grove-back with an arrowtongue at its feet, feeding opportunistically on the prey flushed by the grove-back's movement. Most of the trees on the grove-back's carapace will die within a few months, but their trunks will remain standing for years to come.

The enormous skid carries the rear two-thirds of its body. It is this plow-like growth that one can hear scraping from a distance. But the most remarkable aspect of this already remarkable beast is the forest of dying young plaque-bark trees growing out of its dorsal carapace. At first this was speculated that this might be some kind of protective adaptation that enables it to hide; this seems unlikely, though, given the creature's bulk. It was later learned that once the keeled grove-back reaches this size and age it has no known true enemies and supposedly does not fear predation. Though on rare occasions, an individual roaming near the Amoebic Sea could end up getting impaled and killed by an ambushing colony of Beachquills.

As a grove-back moves along, one can very clearly hear the suction of its breath as it inhales the luminous clouds of microflyers, the minute, airborne animals that make up its diet. This also supplemented by tiny aerophytes.

The reason for arrowtongues accompanying the grove-backs is quite simple. A predictable side effect of the travels of so large a creature as the grove-back is the flushing of enormous quantities of game. The arrowtongues opportunistically follow the huge beast, preying upon this game (even at great risk to themselves).

The large grove-back, for its part, placidly continues on its journey, raising and lowering its broad ax-shaped head, unaware of the dramas being played out at its feet. The creature's breath whistles out of generous gills aft of its nose. The trees on its back crack and rustle with each ponderous, lurching footfall, while the enormous skid turns the ground with a clatter of upturned boulders. The noise of the animal's passage is substantial.

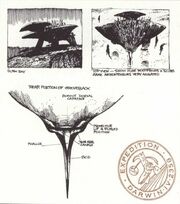

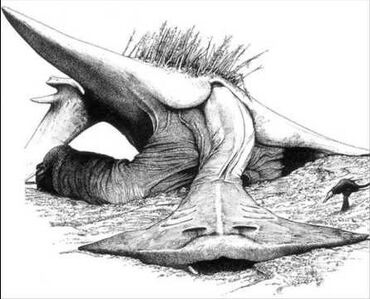

A nesting grove-back will be submerged in a pit and grown over with underbrush and small trees. It looks like nothing more than a small, tree-covered hill. Based on the growth of the trees, it is estimated that the animal has been buried and immobile for at least 10 years, sometimes more. It turns out that the animal is hibernating. During the course of its prolonged stasis, smaller creatures (like bush jumpstars and cobalt jetdarters), as well as plants, accumulate on the behemoth's porous dorsal shell. Each day the faint life signs grow stronger. Eventually there is a 15-meter-long tunnel excavated beneath the animal. Its long ovipositor slowly squeezes eggs into a small chamber at the tunnel's end.

The arrowtongue, thornback, rayback and prismalope roam the vast grasslands of Darwin IV. While the grove-back is also a creature of the plains, it carries a forest on its vast dorsal carapace categorizing it as a forest peripheral.

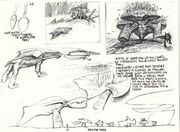

Five days after laying its eggs, the keeled grove-back rises shakily amidst a great cloud of debris and soil. Its stiffened legs, trembling under the immense, forgotten weight, tentatively take their first steps in more than 10 years. The tangled forest on the creature's back shakes like reeds in the wind as it moves forward. After spending the greater part of their lives dormant, these enormous creatures basically rise from the loamy soil to wander ponderously from one breeding ground to the next. The Grove-back’s rare emergence and subsequent feeding coincides with the equally infrequent, periodic expansion of the microflyer swarms. The eggs will hatch in a few weeks.

The young grove-back, unlike the lumbering behemoth it will become, is graceful and fast on its feet. The complex and delicate anatomy of the adult is usually hidden under the soil that covers its carapace.

As first observed by one of the Expedition's human geologists, Dr. Brangwyn, each small young grove-back that hatches and emerges from the sandy soil is covered by sticky amniotal fluids and is pinging feebly. An hour after hatching, the young, which have three functional limbs, dart off in all directions. They are fully independent and seem to delight in their speed, an ironic counterpoint to their slow-paced parent. Only later will their hind limb atrophy to be replaced by the familiar skid, as with the other keeled inhabitants of Darwin IV.

Odd twin fecal trails strewn about come from peripatetic grove-backs. These ruddy, ropey excrescences lie on the ground, on either side of a deep skid-made trench, like double weals, often a meter high and many meters long; before becoming aware of their true origin, some Expedition members had suspected them of being an artifact, possibly of intelligent creatures. They frequently spiral into tight coils or perfect ovoids.

Even in death the grove-back possesses awesome dignity and power. Barlowe was privileged to witness this magnificent specimen's last few minutes of life, and he sketched it just as the first scavengers were arriving to begin their feast.

A sick or aged individual that is dying will awkwardly stumble. It seems to have difficulty with the easy terrain. A dying Grove-back even be struggling feebly to negotiate a small rise.

A dying Grove-back may repeatedly attempt a two-meter rise, almost never quite getting its enormous foot high enough. It will pause a visible tremor passes through it. Suddenly, with a great, roaring exhalation, the huge animal will pitch forward, digging its massive head into the loamy soil. Brittle trees crack and fly, javelin-like, from the animal's back. It seems to take forever for the beast to settle into what will be its final resting place; its feet paw sadly at the ground until at last all is still.

Short moments after a Grove-back's death, something like an Arrowtongue appears, the first of many opportunistic liquivores to arrive at this easy banquet. Soon, at least a dozen larger fierce animals and hosts of smaller scavengers are feeding, all in apparent harmony.