INTRODUCTION[]

Order Paraselenodontia contains over 40 species of herbivorous eutherians that range in size from 5 to 300 kg in weight. The largest members of this group have managed carve a place for themselves amongst niches usually reserved for dinosaurs by thriving in harsh or remote environments that all but a few ornithischians find too extreme. Many aspects of their lives are as yet unknown, due in part to their living in remote locations as well as a general bias amongst specresearchers towards dinosaur-related projects.

FEATURES[]

Specerotheres are terrestrial herbivorous quadrupeds found throughout much of the northern hemisphere and certain parts of Africa. They reach their greatest size and diversity in remote environments like the great northern tundra and Himalayas. They can be divided into the small, primitive lagocanimorphs (dogbunnies) and the advanced specerotheres (caripoos, spelks and dunicorns).

They have sometimes been called 'odd-and-even-toed' ungulates, as they walk on 3 or 2 hooves on the manus and 3 or 4 hooves on the pes.

All paraselenodonts possess the following dental formula:

Upper jaw: I1, I2, P3, P4, M1, M2, M3 Lower jaw: I1, P3, P4, M1, M2, M3

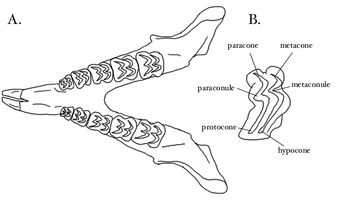

The unique dentition of Paraselenodontia

The first pair of upper incisors and the sole lower incisors are greatly enlarged, giving the lower jaw a diprotodont condition effectively identical to that of certain Ozarel (Home-Earth Australia) marsupials. A wide diastema usually separates the incisors from the closely packed cheek teeth.

Paraselenodont cheek-teeth are generally high-crowned with a unique ridge pattern of that has given their clade its name. Like the selenodont teeth of HE-artiodactyls, the cusps of paraselenodont molars and premolars are arranged in pairs of crescent-shaped ridges, forming a long-lasting grinding surface. However, because of the different chewing actions of these Specworld mammals, these ridges are arranged breadthwise rather than lengthwise (as if an artiodactyl molar had been turned 90 degrees clockwise).

Unlike the side-to-side chewing of Arel ungulates, the jaw action of paraselenodonts is primarily propalinal (back-to-front). This chewing motion is somewhat akin to Arel rodents and is facilitated by an immensely strong medial masseter that attaches to either the zygomatic arch (in lagocanimorphs) or to the side of the snout (in specerotheres). Also like rodents, many paraselenodonts possess large cheek pouches.

All these mammals possess a complex, sacculated stomach which contains a rich bacterial flora to aid in the breakdown of plant foods. Specerotheres also practice rumination or 'chewing the cud'.

HISTORY[]

Precisely where these creatures fit amongst the placental mammals remains a mystery. They bear a number of remarkable external convergences with various Arel mammals but are both genetically and anatomically dissimilar to all other extant clades of both timelines. Preliminary mitochondrial DNA studies suggest that their ancestors had already diverged from other the living spec-mammalian lineages well before the start of the Cenozoic. Intriguingly, this same genetic research indicates that their nearest (though still very distant) relatives are none other than the rodent-like xenotheridians although there is little evidence, anatomical or fossil, to support this idea. Alternatively, the variety of primitive species on the Himalayan plateau would seem to indicate that the paraselenodonts are of Gondwanan stock, arriving in Eurasia perhaps via the India Subcontinent.

Although they may or may not have originated in a different part of the world, most researchers are in agreement that the Himalayan region was the cradle of paraselenodont evolution and was the source of the current crop of living forms.

While small paraselenodont-like teeth are known from Oligocene Mongolia and India, no diagnostic postcranial remains are known from before the Neogene which makes pinpointing their relationships a difficult task.

In the early Miocene, fossils of rat-sized lagocanimorphs suddenly become quite common in Eurasia (a phenomenon consistent with the 'Out of India' model). These forms are already quite advanced (and are in fact more derived than the most primitive extant dogbunny), a clear indicator of a much older evolutionary history.

During the Pliocene, cat-sized representatives of the more advanced suborder (Specerotheria) appear in south-central Asian assemblages. While never particularly common or speciose (rarely more than one species in any assemblage), they soon spread into much of Asia and northern North America but remained exceedingly rare or absent in most of Europe as well as Africa where none survive today.

The formation of the north polar icecap seems to have given these mammals their lucky break in clearing out many of their dinosaurian competitors in the high arctic. During the Late Neogene and Early Quaternary, the specerotheres shot up in size and diversity in the Holarctic, evolving into the collection of long-legged horned beasts that currently dwell in the frigid north.

LAGOCANIMORPHIA (Dogbunnies)[]

This the older and more primitive suborder of paraselenodonts, that today represents about thirty small species scattered throughout Eurasia as well as parts of Africa. They are long-tailed and walk with a digitigrade posture giving them a distinctly dog or foxlike appearance when viewed from a distance. This, when combined with their large incisors and ears has inspired the name 'dogbunny' for these mammals.

Widely distributed in the Miocene, today the dogbunnies are generally found in cool, rocky environments although a few unusual species can be found in the arid plains of central Asia and the drier parts of Africa.

The feet of dogbunnies possess 3 manual hoof-like toes and 4 on the pes, often with additional vestigial digits. Pending further research, all dogbunnies (extant and extinct) are currently lumped together into a single family, the Lagocanidae although this situation will almost certainly change in the near future.

Red Head Dogbunny (Cynoagouti craniorufus)[]

This is a very small (for a paraselenodont) mammal, only 25 cm long, including the tail and a weight of less than a kilo. The scientific nomer refers to their habit of sitting on their haunches like a HE agouti when tackling a big fruit; chewing with frequent nervous looks for predators. Red head dogbunnies are found in localized areas along the subtropical and warm temperate deltas of the Chinese coast. Feeding on fungi, fallen fruits, nuts, leaves and twigs, these little animals spend their days within territorial allotments of an acre or so. Breeding may be anytime between April through September. Forms usually contain an average of 6 kits. Males generally have territorial ranges of one-three acres, overlapping the ranges of several females. Defending these home ranges from interlopers takes up a good portion of their day. The males will chase out young females that can't hold their own against the resident does. Interloper bucks are dealt with more severely with butting by the nasal bosses. Equally sized males will go at each other with their canines. This savaging is quite extreme for such small animals; often one male will be killed or so badly wounded as to die from their injuries.

Blue-Maned Dogbunny (Lagocanis caeruleocauda)[]

By a wide margin, the blue-maned dogbunny (Lagocanis caeruleocauda) is the largest of the lagocanimorphs. An ethereally beautiful animal, the most remarkable features of this creature are the luxuriant blue fur on its neck and tail. A closer examination reveals that this blue coloration is acheived through the mixture of black and yellow hairs.

The blue-mane dogbunnies inhabit remote alpine grasslands and dwarf-scrubland in the Himalayas to just below the snowline, rarely descending below 3500m. They live as mated pairs, which defend a territory against incursion from other blue-manes with the assistance of their adolescent offspring. They are diurnal, emerging from their lairs in the early morning to feed on grass, leaves and lichen.

The dawn and dusk calls produced by blue-mane dogbunnies as they declare their territorial boundaries is a haunting, high-pitched, surprisingly dog-like howl.

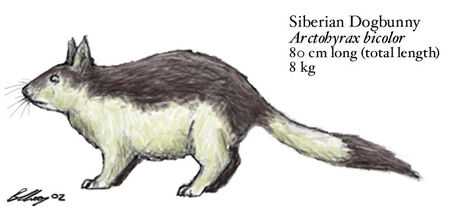

Siberian Dogbunny (Arctohyrax bicolor)[]

The Siberian dogbunny (Arctohyrax bicolor), a small lagocanimorph, lives in cool-temperate northeastern mainland Asia, including the Kamchatka Peninsula. It prefers rocky upland regions where it moves with ease through seemingly inaccessible terrain. It is diurnal, feeding of grass, lichen and plants.

Kitsune (Lagocanis japonica)[]

A close relative of the Blue-maned Dogbunny, the Kitsune can be found throughout the main Japanese archipelago, as well as a few scattered populations in Korea and northeastern China. While a common sight in Japan, Kitsunes are rare on the mainland due to competition with ceratopsians and ealines.

SPECEROTHERIA ("Spelks", Elahrairahs, Dunicorns and Spakas)[]

A dozen or so species of specerothers can be found throughout the Holarctic in the tundra and boreal forests. A few others are scattered around the rest of Eurasia in remote montane or insular environments.

Commonly referred to as caripoos and spelks ("Spec elks"), euspecerotheres are medium-to-large sized mammals with long snouts and short tails. They possess 2 manual and 3 pedal hooves on their feet. Many species possess an unusually fleshy and mobile upper lip. Specerotheres walk with an unguligrade posture.

Most specerotheres possess a variety of horns or hornlike structures on the head. Nearly all possess one or more bony extensions on the temporal ridge that supports a keratinous horn or crest. Many specerotheres also possess facial horns or bosses made out of epidermal tissue.

UNICORNOIDIDAE[]

This monotypic family contains the dunicorn, an unusual desert species from Central Asia.

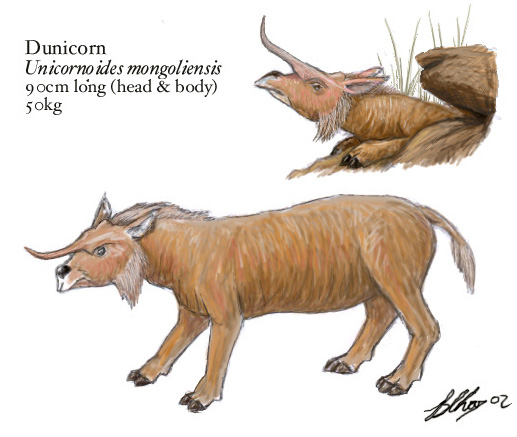

Dunicorn (Unicornoides mongoliensis)[]

This strange, heavily-built specerothere has been characterized as a cross between a dachshund and a rhinoceros. It is a solitary inhabitant of the desert and arid steppe of Spec-Mongolia. Although poorly equipped for major excavation, the dunicorn spends most of the day in a burrow - either finding one abandoned by a a burrowing reptile or mammal or the dunicorn will aggressively evict the occupants. It clumsily descends into the burrow tail-first usually allowing its snout to protrude from the entrance. Its sharp horn acts as a deterrent against predators or the original tenants of the burrow should they return.

After sundown, the dunicorn emerges to feed on grass, seeds and roots as well as the occasional insect. It manages to extract the bulk of its water requirements from these foods and rarely needs to drink.

Mi'raj (Miraj mirabilis)[]

These unicornids are much smaller than their Asian relatives at roughly 15 kilos. Mi'rajs are predominantly members of the maquis and conifer forests of northern Africa and the Levant. They are herding specerotheres that resemble the spelks of the more temperate climes further north. They are one of the few herbivores that will eat death thorns, though they prefer the new growth that hasn't yet acquired their symbiotic fungi.

SPECEROTHERIIDAE (Annelks and Spelks)[]

The members of this family are the largest and most familiar of the specerotheres. They bear a strong external resemblance to the artiodactyls of Arel with long, slender legs with an unguligrade posture and prominent flamboyant horns on their heads. They can be divided into 2 subfamilies.

The Specerotheriinae includes the spelks of the genus Specerotherium and Annelka. These are creatures range from 15-70 kg and are primarily forest and woodland dwellers. They live as solitary individuals or pairs that defend a territory. Spelks often have bizarrely ornamented bony horns or crests that are used for visual threat displays. When this fails, the single sharp epidermal horn on the forehead is brought to bear.

The Tricerotheriinae comprises the three species of caripoo (genus Tricerotherium) which, at 190-300kg in weight, are probably the largest fully terrestrial mammals ever to exist on Spec. Unlike the forest-loving spelks, the caripoos roam the great northern tundra in small to moderate-sized herds. Living alongside the great polar therizinosaurs, the caripoos survive by having powerful chewing capabilities coupled with an intensive digestive process that allows them to tackle less palatable foods than the dinosaurs are usually willing to sample. Caripoos possess a short bony horn on the unusually large (for a herbivorous mammal) temporal ridge and two or more epidermal horns.

The caripoos are so named due to their rather unsavory habit of feeding on the dung of arctotitans and other herbivorous dinosaurs. They swallow the undigested vegetation in the dung and spit out the rest, a process nicknamed "wine-tasting" by spexplorers. Indeed, there are some species of tundra-dwelling plants whose seeds will not germinate until they have passed through the gut of both a therizinosaur and a caripoo.

The Saga of the Caripoo

Annelk (Annelka infuriara)[]

The annelk (Annelka infuriara) is one of the smaller specerotheriine spelks. It dwells in boreal forests across Eurasia, generally preferring areas with a fair degree of undergrowth where it browses on leaves, nuts and fallen cones.

As with all spelks, the annelk aggressively defends a home territory against others of it's species, sizing up its opponent by laterally displaying its hand-shaped temporal crest. This aggression does not extend to other species and the annelk will quickly disappear into the shadows when faced with danger.

This spelk has a unique, high-pitched coughing call (aheh! aheh! aheh-heh-heh!) that is loudly repeated at dusk and soon becomes extremely infuriating to listen to.

Roe Annelk (Annelka capreolus)[]

Seeking out ferns, grasses and forbs to browse in the cool of the evening hours, this paraselenodont is a skittish exception to the normal spelk tradition of maintaining paired territories. These 20 kg animals live in loose coalitions of extended female herds. The hierarchy of does may reach nearly a hundred with their young in favorable areas. Males live in smaller bachelor herds of roughly 5-20.The winter rut have the males facing off by rearing up and boxing with their forelegs. The females give birth to 4-6 leverets in spring in much smaller families of maternal sisters, mothers and daughters. After the young are capable of following the adults, they are introduced into a crèche. By this time, most of the juveniles are already grazing and browsing by this time and milk is little more than a supplement. Indeed, weaning comes within weeks of the crèches formed.

Royal Spaka (Regispaka velocipes)

[]

The Royal spaka (Regispaka velocipes), commonly seen in the Congo undergrowth and along gihungrongo highways and in other such clearings. It feeds mainly on browse, but is also omnivorous, taking anything it finds in the undergrowth, from fungus to frogs. It can move very fast through the forest and can jump astoundingly high for such a small animal in attempts to evade its predators.

Red Spelk (Specerotherium pulchrum)[]

For sufficiently patient observers, the red spelk (Specerotherium pulchrum) is a relatively common sight in the deciduous and mixed forests from Gibraltar to far behind the Ural, nibbling at leaves, gnawing at fallen nuts, or munching grass in clearings. At a total length of up to two meters and a weight of up to 70 kg, red spelks are much larger than any other mammals that share their habitat. The orange-brown fur serves as camouflage against the forest floor; the temporal crest, which can reach a length of half a meter in the largest bucks, as well as the shorter but sharply pointed epidermal horn serve as deterrents to predators. However, all spelks prefer to flee while they still can; the main purpose of the headgear is for keeping fellow spelks out of their territories.

The birth season is in late March and early April; the single young, camouflaged with speckled fur, remain hidden in undergrowth for the first few days till they can keep up with the mother.

Unicorn Spelk (Unicornops unicornis)[]

The Unicorn spelk (Unicornops unicornis) is the only spelk species found in Africa, it is a denizen of the north African forests around the atlas region. It makes a haunting call somewhat like that of a miniature horse, and eats most forms of vegetation as well as fungus and bark.

Sumatra Spaka (Tragulomys pacarana)[]

These are the only species of Spaka native to Sumatra. They can be seen in the lowland areas ususally traveling with the herds of cenoceratopsians native to the area in order to gain protection from the predators in the area.

Asian Spaka (Tragulomys tragulomys)[]

At 30 to 35 kilos, this is the largest spaka. They are also the most widespread, found in tropical/subtropical rainforest across southeast Asia, even reported in monsoonal dry forests on occasion. Populations are known throughout much of Indonesia, where they are sympatric with the Sumatran spaka along the Indian ocean side. The taxonomic position of many races and subspecies is in dispute. The Philippine population seems likely to be raised to species status in the near future. With the exception of the Philippine members, most experts agree that all these distinct races share less genetic diversity than say the two described species of HE clouded leopards Neofelis.

Reproductive habits are different from the Sumatran spaka in that one male shares territory with up to five different females who usually are related. Females begin crèching their leverets together at roughly 2 weeks of age. The leverets are under the watchful eyes of their father during this time as they are lead around the territory and shown food sources and good hiding spots. Should predators attack, the father will attempt to distract them with vigorous jumping and tail flashing to allow a few critical extra seconds for the mothers and leverets to escape.

Stucarib (Specerotherium abrahmsi)[]

The stucarib (Specerotherium abrahmsi), also known as the space moose, is the second largest terrestrial mammal in North America (after the infamous caripoo). It seems to be able to eke out a living in the middle of numerous herbivorous dinosaurs by specializing in plants (mainly herbs and seeds but also fungi of various kinds) that the they can't stomach. The gut fauna of a stucarib is indeed a marvel in itself.

The stucarib has gained its nickname "space moose" from the coloration of full-grown bucks. Unlike the females, their back fur is almost bluish black with a speckled white pattern common to both sexes. This makes the back of the male look almost like a small piece of deep space in the middle of a forest clearing. (Mind you, this is the commonly accepted explanation for the nickname, but not the only one. The most notable of these alternatives refers to the seemingly "spaced out" state of certain stucarib individuals after they've ingested a large amount of noxious mushrooms.)

The call of the male stucarib is a very recognizable "Aaaaaaaarrr" (though described as "faaaaarst" or even "aaaaaarrse" by others). Both sexes sport facial horns above the eyes, but interestingly the branching crest is fully developed only in males. In females the temporal crest is often just barely noticeable as a small bump.

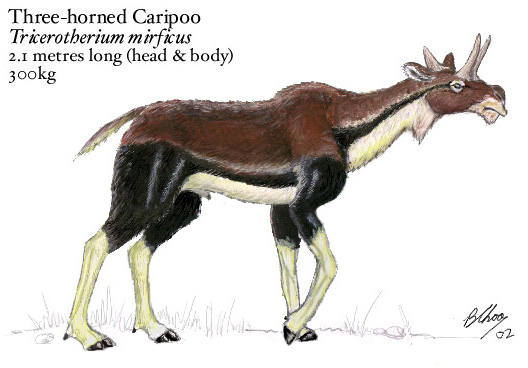

Three-Horned Caripoo (Tricerotherium mirficus)[]

Weighing in at up to 300kg, an adult three-horned caripoo (Tricerotherium mirificus) buck is the largest terrestrial mammal on Spec. Does are slightly smaller, rarely getting above 250kg. They are beasts of the arctic tundra and can be found throughout polar Eurasia as well as northwestern North America where its range overlaps with the closely related American or four-horned caripoo.

Three-horned caripoo gather together in migratory herds of up to twenty animals led by a dominant male. Mating occurs in October. The males in the herd have a brief tussel to see who will be the one to mate with the does in heat this year. However unsuccessful males or those from herds with few females may try to entice does from other herds which can lead to violent confrontations.

During the summer, they graze in the north along with the great arctotitans. With the summer bloom there is plenty to go around for all and the caripoo gorge themselves on a variety of grasses, fungi and aromatic herbs, building up substantial reserves of fat.

During the winter, they are forced southwards, usually trying to remain within visual range of a herd of giant polar therizinosaurs - though usually not getting too close as the carnivorous urgings of its distant ancestry will sometimes surface in an angry or starving tirg. This hazardous association is vital to the caripoo, however, and herds that are unable to find a "patron therizinosaur" almost invariably perish.

Firstly, the dinosaurs provides a limited degree of anti-predator protection. When faced with a drak-attack the caripoo flee towards the therizinosaurs which are usually too focused on the deinonychosaurs to pay much attention to the mammals. Even a sabre-tyrant is reluctant to get too close to an angry and alerted lammox or arctotitan.

The therizinosaurs are, however, far more important to the caripoo as a cheap source of food during this harsh time. With their massive claws, the theropods have digging capabilities of a magnitude that no mammal (save man) has ever possessed. Thus these dinosaurs are able to uncover greenery buried deep in the snow as well as tubers and roots in the frozen soil. Whole families of plants rely on this behaviour for their reproduction, producing fruiting bodies just before the onset of winter that lie dormant in the snow for the scythe-dinosaurs to find.

Yet, for all their digging prowess, the therizinosaurs are limited in the degree to which they can utilise this resource owing to their relatively weak jaws and simple chewing mechanism. Thus the dinosaurs often leave spilt and discarded scraps at their digsites that the caripoo greedily pick over once the theropods have moved on.

Further more, the dung of therizinosaurs contains a tempting mixture of undigested plant fibres and seeds. After an arctotitan takes a dump, the caripoo rush to the dinopat like pigs to swill. They then noisily consume the steaming faeces, which also provides a valuable source of warmth, fights often breaking out over the choiciest bits of poop.

During this time, the caripoo often display an initially confusing behaviour called "wine-tasting". The mammal will stuff its face full of poo until its cheeks bulge before violently spitting it out. The animal is in fact extracting large undigested seeds and nuts by mixing the fecal matter with saliva before squishing it between its teeth. The seeds are lodged between the animal's teeth and the excess poop is discarded. The caripoo then cracks open the seeds and feed on the contents.

This behaviour has apparently been going on for so long that the seeds of certain polar plants attain on optimal germination rate only after passing through the digestive tracts of BOTH a therizinosaur and a caripoo.

Once their scatophagous frenzy has subsided, the caripoo can often be seen furiously cleaning their mouths out with snow. Although this is probably a safeguard against oral infection, one cannot help but think that they are desperately trying to get rid of the aftertaste.