INTRODUCTION[]

No group of dinosaurs best expresses the innovation yet familiarity of Spec’s fauna as ungulapedes. Clearly hadrosaurian in nature, the origins of these dinosaurs extend as far back as the Cretaceous. With over an estimated 150 species, these are one of the most successful groups of dinosaurs in the world of Spec.

HISTORY[]

The ancestry of the ungulapedes was believed to be traceable back to Anserodromeus, a small, crested, basal hadrosauroid from Paleocene-Early Eocene Africa which can has some similar features to basal hadrosaurs from Europe, most notably Tethyshadros and Telmatosaurus.

Africa, like the other two main Gondwanan landmasses, South America and Australia, seems to have kept its duckbills after the K-Pg boundary. Despite a setback in the Late Eocene, when the climatic chaos ended several endemic herbivores, the relatives of Anserodromeus seemingly flourished and diversified, most of the few African Oligocene fossils being quite morphologically disparate ungulapedes. While many forms became bulky giants, echoing the great herds of the Late Cretaceous, one lineage became small, agile miombo runners, gaining their distinctive hand-hoof during the late Oligocene. With the gradual drying of the African continent as the Neogene progressed, the larger, more conservative hadrosauroids went into decline—to the boon of the early ungulapedians, which soon spread into the vacated niches.

While many forms became bulky giants, echoing the great herds of the Late Cretaceous, one lineage became agile woodland runners, gaining their distinctive hand-hoof during the Oligocene. With the gradual drying of the African continent as the Neogene progressed, the larger, more conservative hadrosaurs went into decline to the boon of the early ungulapedes, which soon spread into the vacated niches.

The Pliocene was a time of spectacular evolutionary innovation for the ungulapedes with the Afrohadrosauridae becoming the most numerous and diverse herbivores on the continent. When the long isolation of the African continent ended in the Miocene, great herds of ungulapeds marched across the Sinai into Eurasia. Indeed, these hadrosaurs seem to have driven the large eurolophians to extinction, and may have also helped to drive several other clades of ornithischians and herbivorous theropods extinct. Several North American invasions seem to have occurred, some as recently as the last glaciations, though currently only a few species reside in the nearctic region.

BIOLOGY[]

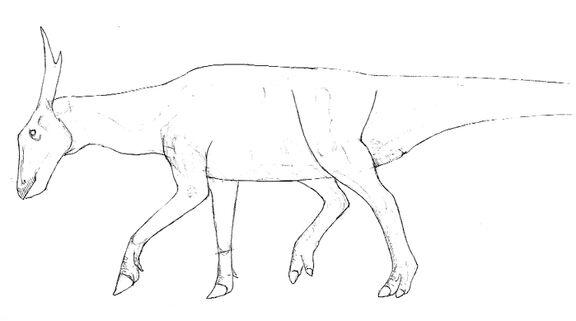

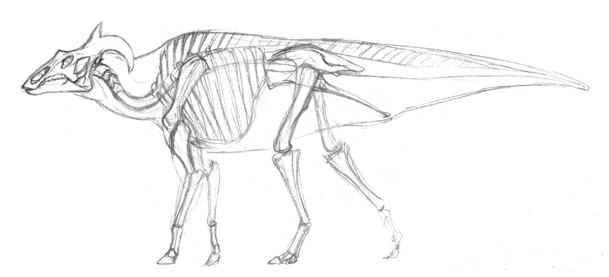

Ungulapedes are most easily recognized by their forefeet. Digits 2 and 3 have become fused and the combined unguals protrude from the flesh to form a single large hoof. Digit 4 is reduced and completely internalized however, the 5th digit remains free in all forms except the elumbe and often bears a large claw.

The most remarkable aspect of these hadrosaurs is not to be found in their feet, however, but involves their reproductive habits. With the exception of the archaic paleungulapodes, the majority of the Ungulapedia has largely or totally abandoned nesting altogether and carries their incubating offspring with them. Most female ungulapedes possess a large, highly elastic gular pouch that can be partially sealed off from the rest of the mouth via muscular contractions. These broodpouches are used for egg-storage and are both highly padded with rubbery tissue both for insulation and to prevent damage to the egg.

The mother ungulapede lays one or two eggs that vary from between 15 to 45 cm in length. Once deposited on the ground, the egg is taken into her mouth and gently maneuvered into the broodpouch. Most species lay either single eggs or produce two but discard or consume one of them. These forms have a simple, single-chambered broodpouch. Some ealines, however will lay and nurture two eggs, their broodpouch having evolved a bifurcated, two-pocketed configuration (bearing a passing resemblance to a mammalian scrotum) allowing them to safely transport both eggs.

With her broodpouch fully laden, the mother is still capable of eating and drinking albeit in a somewhat slow and awkward manner. Sometimes she will remove the egg from her broodpouch and place it on the ground or a brief period while she gorges. Incubation usually takes between 1 and 4 months depending on the species and local conditions.

Upon sensing that hatching is imminent, the mother coughs up the egg and deposits on the ground, sometimes assisting the youngster by breaking the shell herself. Once it finds its feet, the large hatchling is fully capable of fending for itself, although the majority of ungulapede mothers (and some ealine fathers) provides additional protection to their offspring after hatching. The young of highly gregarious species leave their mother's side in a few days or weeks to form juvenile creches, which either head off on their own or stay to enjoy the protection of the entire herd. Those of less gregarious forms tend to stay with their parents for longer periods.

Regardless of parental care, the young feed ravenously and can put on as much as 40 kg in their first month. Most reach sexual maturity in between 2-4 years.

This unique breeding strategy confers many advantages. For most dinosaurs, the nesting period is a dangerous time for both adults and offspring as their mobility is severely restricted. There is the ever-present danger of predators, egg-thieves and natural disasters befalling the nest site. By dispensing with the nest, the ungulapedes have left behind many of these problems at the expense of reduced clutch size. A female with a full broodpouch can still feed, drink, evade predators, tend to her previous generation of offspring or even mate and thus get the next egg ready once the one in the throat hatches.

These benefits become even more vital on the great plains of Africa and Asia where the ungulapedes thrive. Here, vast herds must wander great distances as they follow highly seasonal and irregular food supplies. With this sort of lifestyle, having to spend several months tied down to a static nesting site would be a severe handicap. The development of this brood-pouch is probably responsible for the ungulapeds' tremendous success in Africa and Eurasia where they are they are by far the dominant clade of small herbivores. Indeed, only their intolerance to cold, it seems, has prevented the ungulapeds from spanning the globe. On a recent expedition back to Spec, it was discovered that at least one species has made its way to North America.

Five main clades of ungulapedes are currently recognized:

- Paleoungulapodidae

- Afrohadrosauridae

- Ciraphdadridae

- Ultracornidae

- Formosicornidae

Throat-Brooding Behavior[]

Unlike the viviparous mammalian herbivores of HE Africa, ungulapedes are, as archosaurs, restricted to laying eggs that take time to hatch. Dinosaurs have through the ages of the Mesozoic and Tertiary experimented with varying approaches to caring for their young. Even today, some species simply make a nest and abandon their young to fend for themselves as they hatch and dig their way out of the nest. Most are more caring parents, either actively brooding the eggs with their own body warmth or maintaining a steady brooding temperature in a carefully protected compost-heap like mound nests. Ungulapedes have, however, come up with a completely novel innovation that enables them to take their eggs wherever they go. Only some maniraptorans have come up with comparable strategies.

At some point before the split of modern ungulapedes into afrohadrosaurs and formosicorns, ungulapedes gave up trying to brood a maximum amount of eggs in the hopes that some would survive and took an almost marsupial-like approach: they would lay only a few eggs that would be brooded inside a throat pouch. By investing heavily into a few throat-brooded eggs, the ungulapedes gain in mobility and eliminate the threat posed by nest-robbers. This "brooding revolution" seems to have taken place during the appearance of grasslands and may have been connected to adopting a more migratory lifestyle. Certainly the most notable throat-brooders of today are the migratory African species such as the Sahib saurolope.

African migratory saurolopes commonly lay their eggs during the dry season. When the female gets ready to lay its eggs, the male positions itself behind the female, ready to scoop up the freshly laid eggs into its mouth and into the brooding pouch. In some species only males have the brooding pouch, but some non-migratory species share the responsibility for the eggs, sometimes switching brooders or even sharing the eggs evenly with each other, as is the case in some species that lays up to six eggs, far too many to fit inside one individual's throat pouch. There are even species where the female must brood the eggs, as males have harems of females, and could not possibly brood all their females' eggs.

The eggs laid during the dry season remain in the throat pouch of the parent until the rains come, signaling the beginning of the wet season, a time of plenty for the herbivore. The brooding adult has been proven to communicate with the chicks still inside their eggs with very specific vocalizations that guide the development of the young. If the rains come early, the brooding adult can signal the chick to mature faster and hatch as soon as possible, and if the rains are late, the adult can signal the young to slow down their development and hatch later. The result is that once all the plants spring into life after the long drought, the precocial young are ready to emerge from their shells and begin to feed.

The hatching of the ungulapede young is an occasion similar to that of giving birth to antelopes. The newly hatched young take several minutes before they are ready to walk along their parents, so different species employ different tactics to prevent their young from ending up in the jaws of predators. Some will leave the herd seeking secluded locations for the hatching when the chicks signal their readiness, while others create large congregations where the parents form a living wall between the hatchlings and the predators. After hatching, the young will quickly imprint to their brooding parent, which they recognize based on the communications between the unhatched young and their brooder. The parent will repeat a very similar sound, called the hatching call, to ensure that the hatchling recognizes its parent as soon as it leaves the egg.

The parental care of throat-brooders extends only to providing some protection to the newly hatched young as well as giving them an example of what plants the young should eat. Hatchlings usually start nibbling at plants during their first hours outside the egg. After this they will follow their brooding parent, and within days they are ready to follow the herd and feed by themselves. The hatchlings grow at an incredible speed, being ready to take part in the migration during their first year of life. In non-migratory species growth may be somewhat slower than in migratory species, but the parents usually begin to avoid their young at the beginning of the dry season. After this the young is a completely independent individual, although reaching maturity may still take a year or two.

While saurolopes are the best known throat-brooders, this trait is also found in ultracornids (hornmeister) and formosicorns (ealines and the elumbe). Although ciraphadrids do not throad-brood, it seems likely that they have simply lost this trait due to anatomical changes in the neck. Whether or not the forest-dwelling chotcho throat-broods is still at the moment unknown, as are many other details about this cryptic creature's behavior.

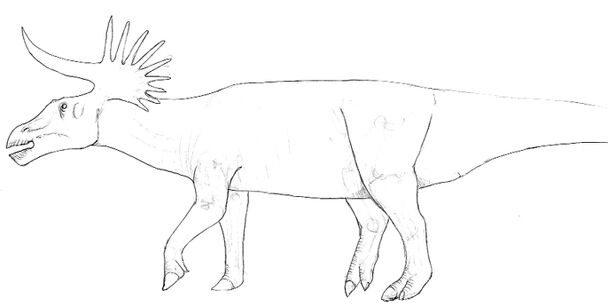

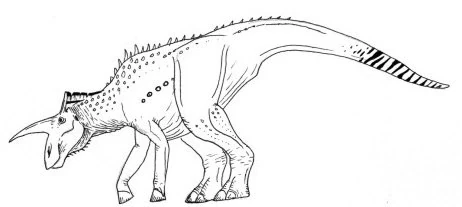

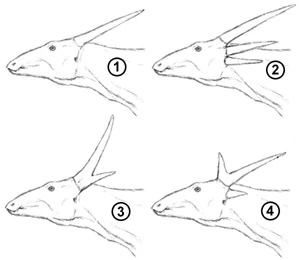

The Four Main Horn Arrangements in Saurolopes:[]

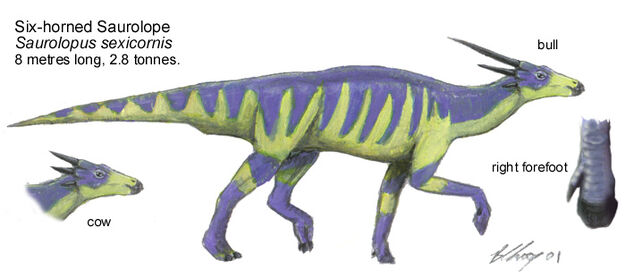

The four main horn arrangements in saurolopes. 1. two-horned saurolope (upper left), 2. six-horned saurolope (Saurolopus sexicornis) (upper right) 3. down-branching saurolope (lower left) and 4. up-branching saurolope.

- Two-horned saurolope (upper left)

- Six-horned saurolope (Saurolopus sexicornis) (upper right)

- Down-branching saurolope (lower left)

- Up-branching saurolope (lower right)

Of these 1 is believed to form a group distinct from the others, while 2, 3 and 4 are believed to share a common four-horned ancestor. 2 seems to have split off first, while 3 and 4 split off later producing various branching structures in their horns. 3 generally has only two pairs of horns, but some taxa retain vestigial second horn pair, while 4 commonly has two well-developed horn pairs. In groups 1 and 2 there is rarely any horn branching, with the exception of some flat-horned taxa within 1.

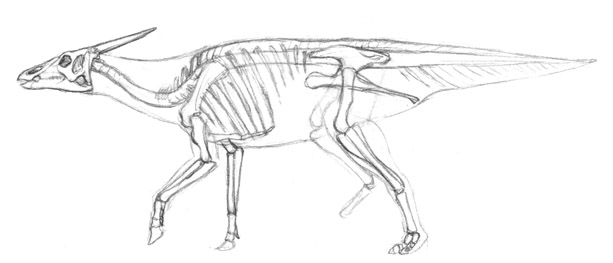

PALEOUNGULAPODOIDAE (Blowhards and oopas)[]

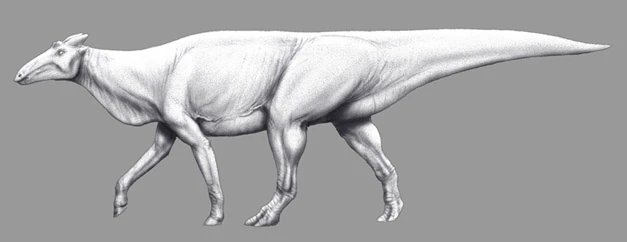

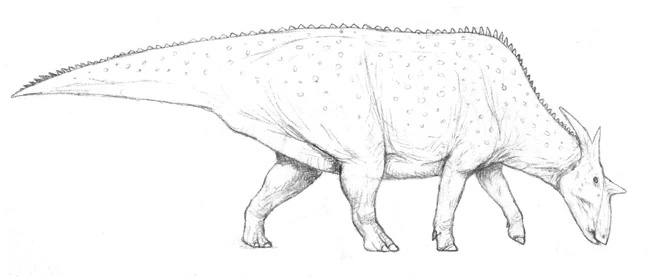

Generally small and completely restricted to southern and central Africa, the paleoungulapods (confusingly it's "pods" not "pedes") are the most primitive extant members of Ungulapedia.

The paleoungulapods are limited to just two species. This relict clade of ungulipedians is apparently quite conservative. Their fossil representatives, which stretch back to late Oligocene/early Miocene times, show essentially the same conservative design. The two surviving species have widely disparate African ranges. Unlike the afrohadrosaurids, the oopas and blowhards have male dominated leks, with the females retreating to dense cover to incubate and raise her chicks alone.

These archaic critters can only be found in ancient habitats such as the eastern Congo or the fynbos of the Cape ranges. Their specializations to these ecosystems may have prevented their extinction from the expanding ranges of their more derived afrohadrosaurid relatives, jackalopes and fuzzy mammals and maniraptors. Both are quite “hairy” critters, with coats of long, fuzzy quills covering most of the body.

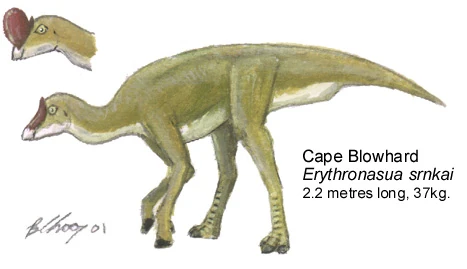

Cape Blowhard (Erythronasua srnkai)[]

The Cape blowhard is a primtive ungulapede that lives in open dry plains of Southern Africa. It feeds on many plant species, eating grass, fruit, tubers and leaves. It is generally solitary, declaring its territory with its distinctive honking call and a comical-looking nasal balloon.

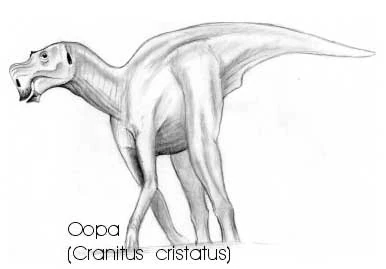

Oopa (Cranitus cristatus)[]

Spec's Congo harbor a number of oddities, relic species from a time when Africa was a lush continent, covered with jungles of which the present greenery is merely a fragment. One of these relics is the primitive oopa, a paleoungulapod most closely related to the blowhards of Africa's southern coast.

Like their smaller cousins, oopas lack horns, sporting enlarged brow ridges and a laterally flattened nasal crest in their stead. These timid herbivores are solitary in their habits, although young calves with trail behind their mother for up to a year before heading off on their own. Males, larger than females and more brightly-colored, can be quite ill-tempered and deliver vicious kicks with their front hooves to any creature stupid or unlucky enough provoke them.

AFROHADROSAURIDAE (Saurolopes, Eendbeests, Lanceheads, Bowhorns and Angarangs)[]

Some 48 described species are known, with an estimated 40 total of species altogether. The saurolopes represent the most successful of the dinosaur herbivores of the Old World Tropics. They range from delicate dorcasaurs to gigantic hornmeisters, elumbes and brutons. These critters represent the vast bulk of Ungulipedia and hereafter, will be referred to by their common clade nomer, the saurolopes.

Afrohadrosaurids have had explosive radiations time and again since the early Miocene. They first disembarked from Africa into Eurasia around 20 million years ago, rapidly traversing much of the Eurasia continent. Many varied tribes waxed and waned over the next few million years. The diversity and number of saurolope species was much greater than at the present day. Fossils have been recovered north of the Arctic circle as recently as the early Pleistocene, and skulls from southernmost Nevada suggests a late Miocene North American range. The Pleistocene glaciers have since weeded out most of their diversity from temperate Laurasia, but several formosicorns still wander the forests and steppes of Eurasia and North America.

They are overwhelmingly creatures of open landscapes. They may be found in miombo woodlands and the driest deserts to grassy highlands. These animals engage in never ending migrations within and without geographical regions in search of food and suitable chick rearing sites. Most species make seasonal migrations of up to 100 miles round trip every year. Some many times that. The duckbucks include the true saurolopes, the lanceheads, whifflebooms and bowhorns. Unlike the other clades, they are monogamous instead of polyandrous. The creatures may be solitary outside of the mating season or form life-long pair bonds (with triads of a female with two males being very common). Most species tend to form small herds in more forested areas, especially close to water in the form of marshes, lakes and rivers. They are more selective browsers, though must graze on grasses intermittently.

AFROHADROSAURINAE[]

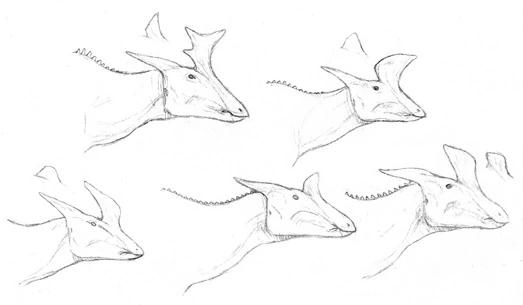

Afrohadrosaurines are generally fairly gracile animals with long square-tipped snouts. Most species have between 2-6 narrow squamosal horns but lack any sort of cranial or nasal ornamentation. All are at least partial grazers; none survive on a completely leafy diet.

Dorkk (Antillosaurus agilis)[]

The dorkk, though more antillopine than many other saurolopes, is still very much like its kin in general anatomy and habit. They are exceedingly common on the savanna, where they range in numbers similar to the impala of our timeline.

Harlequin Duckbill (Genus unknown)[]

There is plenty of room on the savannah for the harlequin duckbill. Being a true member of the afrohadrosaurid family, even considered to be a larger cousin of Oryxosaurus, this species seems to target the lower-growing fibrous species; just like the dietary preferences of the zebra and gnu back on home earth.

Sahib Saurolope (Genus yet to be described)[]

The sahib saurolope is one of the largest oryxosauroid saurolopes. These animals congregate in large herds that take part in the great African herbivore migrations. These animals congregate in large herds that take part in the great African herbivore migrations." But that's about it. The male has an orange and white face but the body colour fades towards a muddy brown in the neck. Despite genetic studies confirming it to be a member of the hartanasini clade of afrohadrosaurs, just like the halequin duckbill, no name has been given to its species yet hence why it is placed in the afrohadrosaur indeterminate.

Eendbeests (Bestianas sp.)[]

Wide-ranging, members of this genus can be found across the entire of open Africa. Some species even range up into the highlands of the Atlas and Drakensberg mountains, while some have invaded Eurasia. They are all dedicated migrants, never remaining longer than a month in any one area. This is reflected within their offspring, who have the fastest growth rates of any ornithischian dinosaurs known.

Eendbeests often follow the great herds of grassbags, lagging several days or so behind them to crop the new grass. They in turn are followed by scores of local jackalopes, other afrohadrosaurids and herbivorous mammals. They are also the focal point for a wide collection of predators and scavengers, ever eager to attend the dying and the dead, walking or not.

Common Eendbeest (Bestianas lesothoensis)[]

First of the saurolopes described, this wide-ranging 700 kilo animal is a beauty of the veldts and Drakensburg highlands. They are extremely cold hardy, often seen tolerating freezing temperatures and summer snow when migrating from pasture to pasture, having thicker quill coats than their relatives. The winter season lasts roughly four months and drives them to valley lowlands, where they hatch out this year’s generation of chicks. During this time, the herds split up into small harems of several dominant females and their egg carrying husbands.

The Common Eendbeests gradually make their way back up the montane slopes in spring, reaching the lush, well watered grassy highlands by early summer. The harems collect together in vast herds traveling along well worn paths centuries, if not millennia old. The surviving chicks are usually over 80 kilos in weight by this time and capable of shivering the cold nights and storms away with relative ease. The main advantage besides the fresh grass is the relative lack of predators compared to the lowlands. Few abelisaurs chance the chill and steep lands, especially if chicks are in tow. Draks, errotyrants and metacanids are generally too puny to threaten any but wayward chicks.

Kenyan Eendbeest (Bestianas kikuyu)[]

Eendbeests are widespread across open sub-Saharan Africa, with some four species and many regional variants described. The Kenyan eendbeest can be found in herds hundreds of thousands strong migrating across the eastern African savannas. These are the smallest of the clade, only 400 kilos adult size. They are the nexus of a vast community of predators and scavengers. Herbivores also depend on the their grazing to expose forbs and tender grass shoots.

Steppe Eendbeest (Bestianas tatarica)[]

Occurring in the cold steppes of Central Asia, the Steppe Eendbeest is one of the most common herbivores in the region, forming massive herds. Not limited to nesting sites like panhas and jackalopes and with a more efficient mastication than spelks, the Steppe Eendbeest showcases ungulapede efficiency in a place where they are ironically less specifically to the catoblepines. Subfossil remains show that these animals ranged to Alaska and Yukon during the glaciations, making them the only afrohadrosaurids to have touched North American ground. A few populations still remain on the arctotitan steppe of the Siberian Arctic and Wrangel Island, far removed from their more populous steppe cousins.

HARTANASINI (Saurolopes, Lanceheads, Bowhorns and Thornderks)[]

The duckbucks include the saurolopes, the lanceheads, whifflebooms and bowhorns. Unlike the other two clades, they are monogamous instead of polyandrous. The creatures may be solitary outside of the mating season or form life-long pair bonds (with triads of a female with two males being very common). Most species tend to form small herds in more forested areas, especially close to water in the form of marshes, lakes and rivers. They are more selective browsers, though must graze on grasses intermittently.

Six-Horned Saurolope (Saurolopus sexicornis)[]

The six-horned saurolope is a creature of scrub and savanna; rarely far from water although it is not closely associated with it. It lives in herds of up to 30 individuals led by an elderly bull with young males forming separate herds of the same size. They feed on grasses and other vegetation.

Green Lancehead (Oryxosaurus chloris)[]

5 species of Oryxosaurus can be found throughout Africa. The green lancehead is found across the eastern savannas, corresponding to our world's Eritrea-to-northern-Angola. It lives in herds of 10-50 individuals, often associating with sauropods or other saurolope species, and feeds on grass and leaves. Green lanceheads can go for long periods without water.

Dappled Lancehead (Oryxosaurus makgadikigadius)[]

The five or so closely related species of the lancehead are found from roughly Kenya south into all the open but fairly well watered country of Africa. Huge concentrations of dappled lanceheads are found within the Okavango basin region. The east African Lakes host at least two species and several variants of lanceheads.

Blazeback Lancehead (Oryxosaurus ornatus)[]

The blazeback lancehead (Oryxosaurus ornatus), is a common, seven meter oryxosaur saurolope of the African savanna. It is a grazer, much akin to the zebra in niche. Herds are usually lead by a monarchic male and female blazeback.

Bowhorn (Quadricornis magnificus)[]

The only member of its genus, the bowhorn is a rather odd saurolope, allied with the lanceheads (genus Oryxosaurus), but distinguished by its branching squamosal horns (as in the megacornid hornmeister). Along with this ornamentation, bowheads also sport a pair of smaller, triangular horns in the region of the cheeks.

Unlike most other saurolopes, bowhorns are solitary creatures, mostly preferring to browse near rivers and forest margins by themselves or in small groups. During the mating season, however, just before the rains fall, large groups of bowhorns may gather together, males displaying their fantastic branching horns and brilliant orange and blue facial markings.

Thornderk (Megavacca spinifer)[]

The thornderk (Megavacca spinifer) is a 2 tonne browsing/grazing saurolope often seen in arid habitats. These medium sized saurolopes can be traveling in herds of up to 50 members or more, roaming the deserts of North Africa and the Middle East all the way down to central Sub-Saharan Africa in search of food.

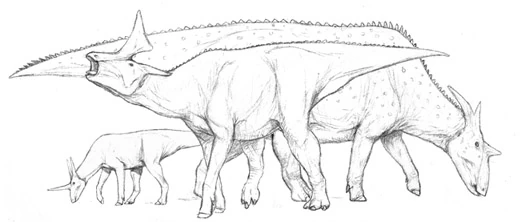

Angarangs (Tonitrobalus sp.)[]

The 3 species of angarangs differ from the other saurolopes in collecting into vast herds out on the open grasslands proper. They may receive most of their water from morning dews and succulent forbs so may rarely drink except during the dry season. Herds hundreds of thousands strong migrate across the land in search of fresh pastures, often following herds of eendbeests who in turn have followed herds of grassbags. The twice cropped prairies expose the forbs and tender shoots that the angarangs prefer.

Although the herds can be huge, angarang females rarely have more than two or four males as mates at a time. The competition between females and the need for males to remain near their harem mistress is exhausting and limits females choices. However, they breed twice a year, usually collecting different males as mates each time. A successful female may “father” up to 200 chicks in her roughly 15 year breeding lifetime. It is not uncommon for nearly half of those chicks to reach breeding age. Compared to other female ornithischians who may lay dozens of eggs every year but see only a handful survive to breeding age in her entire lifetime, it is not hard to understand why the cloacal brooding strategy has favored female afrohadrosaurids as egg dispersers and males as egg protectors.

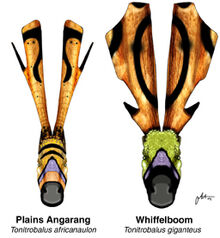

Whiffleboom (Tonitrobalus giganteus)[]

Most angarangs average between 500 to 1,200 kilos in weight. Female whifflebooms may reach over 2,500 kilos. These gigantic duckbucks are found primarily in the Sahel from the Atlantic east to the Indian Ocean. They browse more frequently than other duckbucks, though take grasses during the wetter seasons.

Comparison of the plains angarang (Tonitrobalus africanaulon) and the whiffleboom (Tonitrobalus giganteus)

Plains Angarang (Tonitrobalus africanaulon)[]

The plains angarangs must rank as the most successful of the duckbucks. Several closely related species and regional variants can be found across the warmer open areas of Africa from the Mediterranean south to Cape Horn and into the Levant and India. Herds may exceed a million individuals during the migrations.

Along with other saurolopes, jackalopes and many varieties of maniraptors and even some mammals, angarangs form the basic dietary staple for innumerous species of predators and scavengers ranging from crunchercrocs and african oviraptorids, to cheetaurs and moloks.

Lowland Angarang (Tonitrobalus africanaulon notios)[]

The Swahili or lowlands angarang is a denizen of the grassy areas of Africa’s eastern coast. They tend to live in herds of a few hundred to several thousands migrating constantly in search of fresh pasture. They may head inland many dozens of kilometers but most frequently are found less than 20 kilometers from the sea. They may be seen beachcombing for washed up seaweeds on occasion. Lowlands angarangs are often regarded as a subspecies of the plains angarang, though new research strongly indicates they may well constitute a separate line not only as a species, but as a sister species to all other angarangs.

DORCASAURINI (Dorcasaurs and Bristlehorns)[]

The dorcasaurs or “duck gazelles”, are the smallest of the Afrohadrosaurinae. They typically average between 2 to 4 meters and 80 to 300 kilos. They easily number some 20 species between four genera. dorcasaurs tend to be denizens of the open plains although some species are known from miombo and even xeric Saharan montane woodlands.

Dorcasaurs are the most gracile of the afrohadrosaurines, capable of reaching speeds of between 60 to 110 kilometers per hour. Related siblings tend to form herds of roughly 4 to 20 individuals and monopolize a female or two during the breeding season. The chicks are equally shared throughout the group.

Unlike other saurolopes the “husband guarding” of the larger female is not as effective, since the males often are quite concentrated on each other for the right to mate. They also aren’t as capable of detecting through scent whether a female has recently mated or not. Cuckoldry is much more common in this clade than among other saurolopes, with females sneaking off into the bush with wandering males unrelated to the kidnapping herd of males. These trysts are usually late at night or during crepuscular hours. The majority of other saurolope clades have much better olfactory and visual capabilities in this regard and cuckolded males will promptly eject the eggs and crush them in “spite”. That has resulted in fairly faithful polyandrous “monogamy” among other saurolopes.

Nevertheless, the sibling male harems usually ensure at least 70% of all eggs throat brooded are genetically theirs. There is a good reason for the continuance of “cheater” males, they overwhelmingly are low status males from nearby harems trying their luck elsewhere.

Dorcasaurs prefer tender grasses and forbs overlooked by their much larger relatives. They also specialize in more toxic forage than jackalopes and glucks are willing to sample. This combination of dietary habits has allowed them to expand into smaller size and more densely wooded areas. They actually seem to have displaced some of the nascent larger African jackalopes present during the Pliocene.

These dinosaurs are a favorite prey base for cheetaurs. Juveniles are frequently ambushed by metacanids and weaselcrocs. Azhdarchid pterosaurs have been seen plummeting down into a congregation of adults with their chicks to snatch a baby away. Nevertheless, predation among chicks is not as bad as starvation and simple accidental death, both of which contribute to most of first year chick mortality. By comparison, predation makes up a puny 20% of chicks dying. Should they survive their first year, most dorcasaurs can expect to live an average of 12 years.

Cape Dorcasaur (Dorcasaurus gracilis) []

The cape dorcasaur is the fastest and smallest of the saurolopes. They seldom exceed 2.5 meters in length, and are known to attain speeds comparable to those of springbok and American pronghorn antelopes. Cape dorcasaurs are mixed browser-grazers, and are notoriously skittish, and outrun all but the fastest abelisaurian predators.

Guelta Dorcasaur (Dorcasaurus pansaharansis)[]

The guelta dorcasaurs seems to have originally been limited to xeric montane woodlands in the western Sahara. However, the wet period lasting from 10,000 to 4,000 years ago allowed an explosive advance across the entire of North Africa, even into the Levant and Arabia (where it is the only dorcasaur present). Loose herds numbering up to 500 paternally related individuals may roam over vast home ranges centered around permanent “gueltas” in the form of rivers, lakes or spring fed oasis.

Savanna Dorcasaur (Dorcasaurus vulgaris) []

Abundant throughout the east African savannas, this dorcasaur has close relatives in the Sahel and the open grasslands south of the Congo and Rift valley. They form huge herds of up to several hundred thousands during harsh droughts. These herds migrate to fresher pastures, following the seasonally migrating eendbeests and grassbags. Occasionally, they have to cross rivers; where they become prey to crocodilians and terrestrial predators encouraged by the confusion.

Jazelle Dorcasaur (Dorcasaurus velox) []

This speedy little savanna saurolope, the jazelle dorcasaur is one of the fastest ornithiscians alive, reaching similar speeds to the American antelope (Antillocapra sp.). This species of dorcasaur grows up to lengths of 3 meters and weighs around the same amount as as the viris of the Americas.

Kalahari Dorcasaur (Sothodorcasaurus kalahariensis) []

The Kalahari dorcasaur is well adapted to the infrequent rainfall and harsh seasons of this land, herds hundreds, thousands strong roam in never ending migrations for pasture. They tend to have a more varied diet than other dorcasaurs, often browsing from scrub and desert adapted cycads, manglar shrubs and palms among other plants.

African Bristlehorn (Xenocornis major)[]

The African bristlehorn, largest of all saurolopes, rivals the great hormeister and elumbe in size, and is quite dangerous. These large-bodied marshdwellers are generally solitary, shunning their own kind out of breeding season. They are sometimes seen browsing alongside herds of mokele for protection.

Asian Bristlehorn (Xenocornis pseudosivatherias) []

The Asian bristlehorn was long an enigma among the afrohadrosaurids. It was first believed to be a formosicornine, something in part aided by its Indian location and robust bulk. However, it has shocked everyone by proving to be a dorcasaur. This semi-aquatic dorcasaur isn't just the largest of the dorcasaurs, it is the largest afrohadrosaurid period, competing in size with the hornmeister. Adult females can reach a staggering 11 tons, even larger than their African cousins. The Asian bristlehorn is further shocking by nesting firmly within the mainly African based dorcasaurs, this also applies to its African relative, related to both Dorcasaurus and Sothodorcasaurus.

Whatever their clade placement, these gigantic herbivores can be found in tall grass marshes across much of the Indian sub-continent west into China, all the way into the Yangtze estuary. Their greatest concentrations are to be had around the Himalayan foothills. The perfect combination of abundant rainfall, well drained floodplains and intense dry season fires creates the most magnificent tall grass prairies Earth has ever known in either timeline. It is still a mystery as to why this dorcasaur developed the path it did. No fossils are known, and the dorcasaur fossil record as a whole is rather spotty, with a few remains known as far back as the late Miocene.

Female bristlehorns pursue male mates for weeks at a time. The receptive male releases pheromones signaling his readiness to incubate eggs. The male will trot for many days at a time, this ensures that the female he mates with doesn't sneak any fertilized eggs from other males as well as prove her fitness to defend him within the territory if he calls on her.

CIRAPHADRIDAE (Cirafs) []

Not as widespread or specious as the related afrohadrosaurids, the ciraphadrids are somewhat more diverse. Occupying both moose-like, swamp-dwelling forms, as well as deep-forest browsers and the familiar high browser of the savannah, the evolutionary success of the ciraphadrids is indisputable.

Miocene fossils demonstrates this clade was once far more widespread than today. These oddly hornless afrohadrosaurids - a somewhat disappointing feature, considering Afrohadrosauridae’s most spectacular members, extinct or alive - could be found in significant numbers across Africa and much of Europe until the Pliocene. Today, they are limited to just six to seven species with hugely disparate ranges.

All ciraphines engage in more browsing behavior than any other afrohadrosaurids. Grasses tend to make up a very marginal part of their diet, usually just for nutritional deficiencies. Ciraphines also are pair bonders, they never congregate in herds of unrelated individuals as a general rule except during seasons of harsh stress. Genetic studies reveal that these animals diverged from the rest of Afrohadrosauridae as far back as the Oligocene, and indeed they possibly the first saurolopes in the fossil reccord, if the mid-Oligocene Eocirapha.

Chotcho (Tussisaurus timmledorfi) []

Th chotcho (Tussisaurus timmledorfi), recently discovered in Africa's Congo Basin, bears a close resemblance to the probable generalized browsing ancestor of Ciraphidae. It is the smallest member of Ciraphadridae and was originally mistaken for a paleoungulapod because of its size and lack of proper evidence, save for occasional brief sightings, only found in the deep Congolese rainforest. Once recovered, the holotype specimen proved beyond any doubt that this cryptic animal was an unusual ciraphadrid. Chotchos are often found near waterways and may use water to escape from predators. They are named after the loud coughing sounds that they make when frightened or otherwise agitated. Chotchos have small horn-covered bumps similar to those of the ciraf, which may hint of a close relation.

Ciraf (Ciraphadrus longicervix) []

The ciraf, African high-browser of the smallest type, is often dwarfed by the titanosaur giants with which it lives. In the Africa of our home timeline, however, this 7.5 m long ungulaped would be one of the largest animals of the savanna. These animals tend to live in extended families of a mated pair and their offspring of varying years.

Congo Ciraf (Miombociraphihadrus paraokapia) []

Despite its common nomer, the Congo ciraf is actually a denizen of the rich miombo woodlands surrounding the Congo rainforest. Although it is rarely sighted, spoor and freshly killed carcasses shows this 2 ton animal is actually quite common. They are frequently taken by large abelisaurs roaming the woodlands. One would wonder how such a high rate of predatory attrition would be offset. This riddle was solved when it was discovered that males and females carry up to four eggs within their cloacal brooding sacs.

Cyprus Ciraf (Nicosiaciraphadrus nanus)[]

Aside from formosicornines, few afrohadrosaurids are known in the European realm. The rare Cyprus ciraf is one of them. This tiny 150 kilo animal is a browser of the montane forests and scrublands. These red and white striped critters are poorly studied, as their scrubby montane home doesn’t lend themselves to easy observation. It is believed that they arrived sometimes during the Miocene, when the Mediterranean dried into a salt desert, and the ancestral ciraf shrunk down to the relatively tiny dinosaur of today.

Greenbeestle (Chlorotherium cornuta) []

The highest browsing forest saurolope is the greenbeeste, a dense forest cousin of the ciraphs, endemic to the otherwise undaur-dominated Asian rainforests. With black and green mottling all over its body, it moves gracefully through the forest periphery, almost imperceptible against the green curtains surrounding it.

Okapp (Cryptociraphadrus ornatus) []

Also known as the buluebeeste, this might be the rarest of the ciraf clade. It has only been seen a few times, which have lead some to doubt the existence of this enigmatic creature. The animal is said to be patterned with a very cryptic coloration, and is extremely hard to find in the Congo jungles.

ULTRACORNIDAE (Hornmeisters) []

This monotypic family contains the giant browsing hornmeister, the only ungulapede to combine a unicorn-spike and four squamosal horns. Fossil ultracornids both larger and smaller than the extant species are known from Mio-Pleistocene Africa and Eurasia. Phylogenetically, the hornmeister falls midway between the Afrohadrosauridae and the formosicorns, and seems to represent an early sidebranch on the evolutionary line to Formosicorna. As of now, only one species of Ultracornidae is known to exist.

Hornmeisters (Ultracornis benseni) []

The largest African ornithischian, this 10-meter animal is still dwarfed by the giant grassbags with which it often associates. A creature of savanna and and open forests throughout eastern and southern Africa, the hornmeister lives in large herds, usually of around 30-50 individuals but occasionally up to 200. Old males tend to be solitary. It feeds on leaves and tender branches and sometimes digging for tubers. Old females tend to be solitary. These giant cows are much sought after by males when they enter heat; only the largest males win the right to mate and brood her eggs. They feed by dredging up corms and stems from aquatic plants as well as grazing along shorelines. Hornmeisters also reach up to nearly 4 meters to rip down branches for select trees. Fathers frequently will “walk down” saplings and high scrubs to feed both themselves and their offspring.

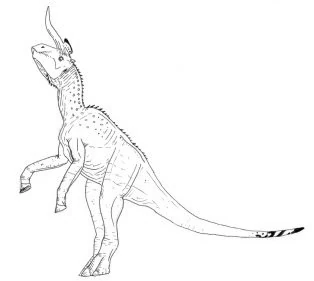

FORMOSICORNIDAE (Elumbes, orths, catoblepines, and ealines)[]

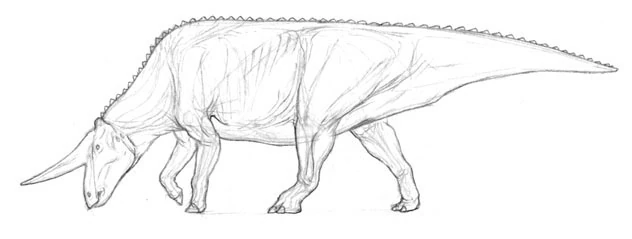

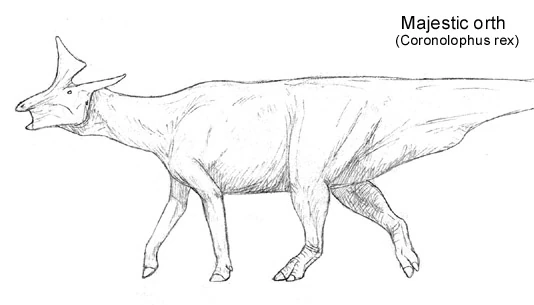

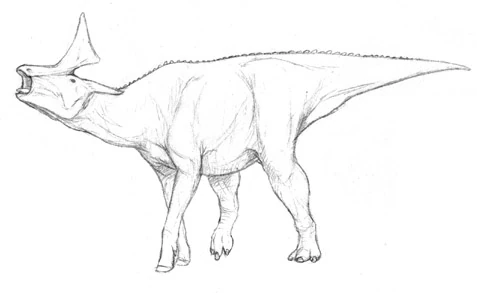

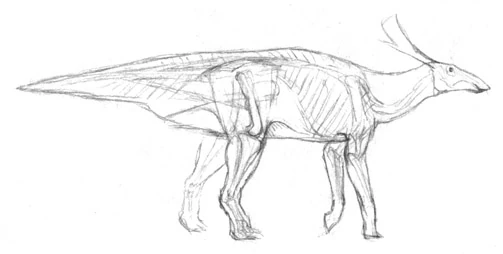

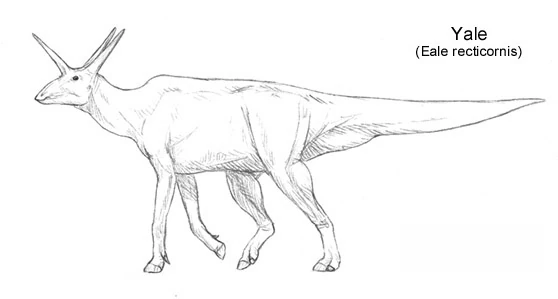

The three branches of Eurasian Formosicornidae to scale. From left to right: yale (ealine), majestic orth (coronolophid), and bruton (catoblepine).

Formosicornidae is a largely Eurasian ungulapede radiation somewhat related to Ultracornidae. The taxonomy of the formosicorns has been a nightmare of duplicity and classificatory juggling with different species grouped in the families Cornucantinae, Ultracorninae (in part), Afrohadrosauridae (in part), Catoblepidae and Ealinae. At one point, the formiscornids were even given their own sub-class, Formosicornia, ridiculous as that may sound. Recent DNA-hybridization data and exhaustive anatomical and palaeontological studies have shown strong support for the monophyly of these seemingly disparate forms in a single family-level clade, Formosicornidae. Formiscorns differ from the African ungulapeds in having larger nasal cavities, the presence of circumnarial depressions and a maximum of 2 squamosal horns. They and the African hornmeister share a distinctive "unicorn horn", a spiky protruberance on the forehead whose horny base is formed by a fusion of the frontals (and sometimes the nasals) into a rugose lump. Formosicorns generally exhibit a lesser degree of sexual dimorphism than the other large ungulapeds, with both sexes often sporting spectacular horns. With the exception of some catoblepids, the formosicorns do not form herds of the same as magnitude as the African saurolopes.

Formosicorns originated in Africa from basal "proafrohadrosaur" stock in the Early Miocene. While their afrohadrosaurid cousins became grazers, the early formosicorns stayed fairly generalized and were amongst the first species "off the boat" when the link with Asia was formed. They proved to be the most adaptable of the invading ungulapeds and soon diverged into dozens of species. With the exception of the bulky grazing cornucantids, most of these were lightly-built browsers living in the shadow or the now extinct giant afrohadrosaurs and ultracornids. With the onset of the Ice Ages, the formosicorns proved to be better able to handle the cooler conditions than the their cousins. In a very short space of time, the family underwent another explosive diversification event producing a host of new Pleistocene forms, including the armored grazing catoblepines. While they lost ground to the saurolopes in their ancestral African homeland, the formosicorns wasted no time in becoming the dominant Eurasian ungulaped clade. The last glaciation period hit Europe's ornithischians hard, driving the last of the local ultracornids, saurolopes and cornucantines to extinction. The modern ungulaped assemblage largely repopulated Europe from other parts of Eurasia. Such immigrants include the tricorns and catoblepines (which extended their annual migrations to Southern Europe even during the glaciation, but didn't spend the winters there). Since the climate has again started to get colder predicting a new cycle of glaciation, the hadrosaurs are no longer found north of the Baltic. 6000 year old bone findings, however, prove that catoblepines once roamed near the Arctic Circle.

CORNUCANTINAE (Elumbes) []

In Africa, with the afrohadrosaurid saurolopes now dominating most of the large herbivore guilds they are restricted to the giant elumbe, a few small ealids on the North coast and a some plesiomorphic old-endemic forest forms.

Elumbe (Cornucantus belli)[]

The elumbe is a recent immigrant from Europe, the largest and last survivor of the Cornucantidae, basal formosicorn behemoths (closely allied to the catoblepids) that flourished in Plio-Pleistocene western Eurasia, but succumbed to extinction in Europe during the last Ice Age. At up to 8.5 m in length and weighing in at a little under 7 tonnes, it is by far the most massive of the ungulapeds.

Notable features of the elumbe include the loss of digit 5, the enormous "unicorn-horn" whose base is formed from the fusion of the frontals and posterior nasals, equal-sized pedal digits (the middle toe is enlarged in extant Eurasian formosicorns) with relatively small unguals and reduced squamosal horns. It feeds primarily on grasses but will also take some leaves and tubers. It also drinks a lot, staying close to reliable water sources. The elumbe is a solitary, territorial animal, coming together only to mate. The single calf is raised by the mother alone. They are nearsighted and bad-tempered, charging at anything that moves, a trait shared with some of the cenoceratopsians native to Spec-Africa. Extremely hardy, elumbes can concentrate water from dew to a great extent. The beasts can even extract a huge quantity of moisture from desert succulents and even get water from carbohydrates consumed from dry twigs and grasses. However, that does not explain their willingness to cross such terrifying areas such as the Empty Quarter and the desolation of the Western Sahara lowlands.

A clue might be in the intense pair bond of elumbes: both sexes pair for life, raising the single chick born every three years between them. Elumbes also seem to have an unerring sense of water, they will often dig many meters below sand and even rocky soils to access springs. They don't just stop there; the nascent water hole is further evacuated with repeated visits until it is a sustained spring. These newborn oases are rapidly seeded with plant life from dormant and windblown seeds who continue to draw up water from the water table. Other animals besides elumbes move in to shit out more plant seeds and graze the rich foliage. The end result is that desert paleowaters from subterranean springs dot the landscape even in the deepest sandy hells every 40 to 100 square kilometers or so.

This makes the elumbe a keystone species of staggering proportions. Flora and fauna extends much further into the subtropical deserts than would be expected. Even rainfall patterns are more rich: desert monsoon rains are nearly double than what HE receives, although even that is a paucity for many areas. Even the deepest desert will receive at least an inch or two every year. The evaporation of water from the gueltas isn't detrimental, most of it will return with the seasonal monsoons back into the sands and soils to rejoin the ancient aquifers under the desert surface.

However, that doesn't make the deserts a rich Eden. Knowing the sources of food and water is an intensive learning process passed on from parent to child. Elumbe for all their size are remarkably cognizant, with deep memories. Parents may lead herds containing their offspring of several years for many decades around their local territory of many square kilometers. This is invaluable knowledge, allowing them to find the best food sources, when to enlarge a guelta, even when to settle in during the worst of the summer seasons.

Desert Elumbe (Cornucanthus belli belli)[]

Smallest and least aggresive of the elumbes, the desert elumbe grows no bigger than 6 meters long and stands as tall as a man, and can be found roaming the Sahara Desert, the Middle East and areas near the Nile River. Unlike the largely solitary elumbe and Sahel elumbe, the desert elumbe can be seen traveling in small family herds of up to 15 members, usually led by a dominant bull and cow. Spexplorers familiar with desert elumbes loved how they could actually walk with a family, even petting them while trudging across the sands.

Sahel Elumbe (Cornucanthus belli shaelensis)[]

Another subspecies of elumbe can be found throughout the Sahel region, trotting through the savannas, grasslands and shrub-lands in search of scrubby vegetation. Behaviorally, they are still elumbes through and though; it was a Sahel elumbe that was responsible for crippling the large male molok which was later killed by the thebirds - suffice to say that even had the molok not encountered the cityfinch colony, it would not have been making any more molokettes.

There is some debate on whether to separate the Sahel elumbe from the true desert elumbe, or whether or not these are actually subspecies of the elumbe, since Sahel elumbes tend to be solitary except for a father and his chick. Desert elumbes are wary, inquisitive creatures while Sahel elumbes tend to be aggressive, bad-tempered animals. The differences between the two variants are so great morphologically and behaviorally that strong calls have been sounded to separate them as two species.

Another possibly distinct elumbe population resided in the last glaciation's massive arctotitan steppes, ranging even into Yukon, but disappeared as the glaciation ended, for reasons poorly understood. The most likely answer being that these species of succumbed to the effects of climate change.

CORONOLOPHINAE (Orths)[]

The diversity of horn shapes among orths, beginning from top left: cuinocco (Cervicerosaurs mirabilis), dwarf orth (Freticornis planalophus), dhar (Stephanolophus indicus), majestic orth (Coronolophus rex) (female), brass orth (Coronolophus orichalcum). The female's horn is drawn beside the head of the male.

The coronolophids, or orths, were the first group of formosicorns that split off as the clade migrated into Europe. These creatures are relatively primative, with rather weak jaw muscles that restrict their diets to tender leaves and shoots. Despite their gastronomic limitations, orths are quite common in western-central Eurasia, with populations extending north to Fennoscandia and the British Isles and into southeastern and eastern Asia. These herbivores are larger than most ealines (though not so large as the catoblepines) and are distinguished by their large, flattened central horn (morpholgically the same as the ealines' "unicorn horn") which is covered with skin. Unusually, most orths hibernate during the winter months. Those who have observed orths and their behavior, it has been noted that they are noted to sound like some one a mistreating brass instrument; as a combination between wapiti and trombone.

Majestic Orth (Coronolophus rex) []

The 8 m long majestic orth is a prime example of the typically European hadrosaurs, the orths. The males' large crest-like central horn is covered with skin which is brightly coloured during the mating season. Males are also larger and more robust than females. Orth males gather a harem of females which they guard from veldraks and other males.

Regina's Orth (Coronolophus regina)[]

The Regina's orth is an 8 meter 3,000 kilo denizen of the abundant miombo and scrub woodlands stretching across much of India, Persia, Anatolia and southeastern Europe. They gather in herds of up to 200 individuals during the dry season as protection from the Ravannas among other predators. Females collect harems of two, occasionally three males once a year. These harems often are lifetime associates, though divorce isn’t uncommon.

Brass Orth (Coronolophus orichalcum)[]

The third species oand rarest of the genus Coronolophus, this recently species of orth can be found through out the forested areas of the Eurasia continent, mostly in Europe though. Sightings of the brass orth have reported in North America, but more search will be conducted into this matter. Unlike the majestic orth and the Regina's orth, these creatures do not live out on the grasslands in large herds, instead preferring to live in smaller family herds in which males and females usually mate for life. Their name stems from their echoing calls, which sound like someone playing a brass instrument in a deep, deep pitch.

Dwarf Orth (Freticornis planalophus)[]

The second-smallest species of orth can be found in both of the British Isles, both Ireland and England. For the Ireland population, adults enjoy a life free from predators while their offspring are more at risk, especially from predatory avisaurs. The British population, however, both babies and adults, face predators in form of avisaurs, mammals and the grendel, a subspecies of forest bruiser. Dwarf orths can also be seen traveling alongside the British population of cuinoccos, another member of the coronolophinae, for protection from predators.

Mediterranean Pygmy Orth (Freticornis exiguus)[]

First observed by famed specexplorer Mette Aumala back in 2002, but never fully described until 2017, the Mediterranean pygmy orth is the smallest species of coronolophe, and is native to the various islands around the Mediterranean Sea, most notably Malta, Sicily, Cyprus, Crete, Corsica and Sardinia. The most likely ancestor of this rare animal is an as-of-yet undescribed species of Coronolophus recently unearthed in Pliocene deposits in Italy, which eventually decreased in size to accommodate its shrinking habitat.

While small subspecies of mokeles browse the trees and aquatic plants through the islands, pygmy orths can be seen browsing the low growing plants in the area, and occasionally beachcoming in order to feed on washed-up seaweed along with the malta yale; another species of ungulipede native to the Mediterrianian. Growing up to lengths of no bigger than 2.5 meters, pygmy orths, up until now, were thought to enjoy a life free from the land based-predators that worry their cousins in Britain and Ireland, though occasionally a sea journey will put them at risk of attack from sharks or mosarks. It was first believed that these small orths enjoy a life free from predators, however, the discover of predatory avisaurs and small abelisaurs says other wise.

Male pygmy orths are much larger than the females, and mating seasons usually takes place between the months of December to February. After a female has chosen a mate, she will give birth to 5 offspring. Unfortunately, most of them will be eaten by a variety of mammals and lizards; in most years, less than 2 to 3 hatchlings live to see adulthood.

Dhar (Stephanolophus indicus)[]

The dhar (Stephanolophus indicus) is one of the several species of ungulapede native to southeastern Asia. As with most cornolophs, their herds (which can range into the hundreds or even thousands of animals) are usually led by a dominant bull. These herbivores follow the massive brachioceratopsians and titanosaurs, though like many orths they rely on herding behavior to protect them from predators.

Dhars have a rather problematic taxonomic history. First described as Incornis mitis after the analysis of a dead specimen, said dead specimen turned out to be a separate genus entirely. Much confusion with the very similar and contemporary kahn orth followed, until finally the dhar was determined to be its own genus.

Phortorth (Photor sappimus) []

Almost as large as a majestic orth at 7.5 meters, but probably more closely related to the cuinocco, the photorth is is a beautiful and secretive denizen of the jungles of south and southeast Asia. Traveling in small family herds. For most predators, the photorth is not an easy prey; with a temperament rivaling the likes of the cenoceratopsians in the area as well. Even the ravannas, tarasques and draks in the area would think twice before attacking an adult photorth during rut season; it doesn't help the fact their is a confirmed account of a young tarasque who tried to attack a full mating pair of photorths during that season, only for it to succumb to wounds from the horns of an enraged pair of photorths in love. Male photorths have three horns on their head, while female sport one large and sharp unicorn horn in the place of an orth's normal decretive crest. The males are aggressive during rut, but the females, with their sharp unicorn horns, are lethal. When the rut season ends, the personality of the photorth returns to that of a docile herbivore.

Cuinocco (Cervicerosaurs mirabilis)[]

Cuinocco, Cervicerosaurs mirabilis (Temperate Eurasia, Scandinavia, Africa (though South of the Nile Eustary), Eastern Asia and British Isles)

The Cuinocco is the largest of the orths. They regularly reach 10 meters and over 4 tons in female specimens and males are not much smaller. Such a large animal also has suitably a very large range, occurring across temperate Eurasia, from Portugal all the way to the Pacific coast of China, from as north as south Sweden and the British Isles to as south as the Nile Estuary in Africa and as Sri Lanka in Eurasia, only absent from extreme desert climates in it’s range. Preffering dense forests, these enormous dinosaurs are quite shy, found mostly in pairs, the exception being on particularly hostile winters where the dinosaus focus on clearings. In the forests of Europe, they are among the largest land animals, and while nowhere as destructive as sauropods, Brutons or ceratopsians, a pair of Cuinoccos can easily shape a forest, devouring great portions of the canopy and eating young trees, creating clearings and small corridors, followed by a myriad of herbivores from spelks to therizinosaurs. During winter months, animals in the colder regions of Europe turn to conifer needles, though otherwise they entire diet is based on angiosperms. Like other cold loving ornithischians, it bears a characteristic integument plasticity: during warmer times, it’s has simple, wire-like feathers, forming a small or even sparse coat, but a week of low enough temperatures sets the development of a dense plumage, with down forming a thick undercoat while longer, harder quills form a bristly external layer.

Ponik (Ponikosaurus potamicus)[]

Moose-like ungulapedes, poniks can be found near rivers and lakes all throughout Europe, feeding on the vast abundance of aquatic plants. Once thought to be a member of the Catoblepinae, more in-depth research has determined that the poink is actually a species of coronolophe.

CATOBLEPINAE (Gonnucs and beluboses) []

The catoblepines are the largest Eurasian ungulapedes. Like their cousins, the ealines, they are primarily grazers which often gather in huge migratory herds. In contrast to the graceful running ealines, however, the catoblepines have become so massive that they cannot manage anything more strenuous than a brisk amble. The middle toe of catoblepines is not as enlarged as those of ealines with no significant reduction of the other toes. The unicorn horn is generally either a short spike or a flattened boss. The horn-base in catoblepines is formed by the fusion of both the frontals and the posteriormost nasal bones. Though their large size and horns already make them formidable adveseries, catoblepines also possess armour protection in the form of numerous small osteoderms. The first catoblepines seem to appear in Asia Minor during early Pliocene, and probably evolved from primitive ealines. Later they evolved into humongous sizes, taking over the niche of the eurolophine rhinolophs, despite the larger eurolophes being gone, the smaller eurolophes managed to survive. Since the climate has again started to get colder, the hadrosaurs are no longer found north of the Baltic. 6000 year old bone findings, however, prove that catoblepines once roamed near the Arctic Circle. Their calls have been known to sound like mongolian throat singing, but about a few octaves down.

Gonnuc (Bonnacon malleocranium)[]

The Indian catoblepine, the gonnuc, hasn't grown nearly as big as its European relatives, because ceratopsians still dominate the large herbivore niches in southern Asia. It lives in small, loose herds, where the dominance among males is determined by butting contests. As a result, the gonnuc's central horn has evolved into a large, flat boss.

These 3,700 kilo herbivores roam the subcontinent in herds of up to 500 hundred strong. Old post-reproductive females are at the fore guard, protecting their mates and chicks from ravanas and draks. The central horn has developed into a large flat boss that is used equally on intraspecifics and predators. Predatory deterrence is much more enthusiastic, with 40 km/h charges ensuring that all ravening predators get the quick chance to either retreat and think twice about attacking; or never retreat at all.

Gonnuc, Bonnacon malleocranium (South Asia) and Belubos, Catoblepas bucinator (Central and Eastern Eurasia)

Belubos (Catoblepas bucinator)[]

The belubos was the first publicized catoblepine, though certainly not the first observed. Often weighing in at over 2,000 to 3,800 kilos, this animal is extensively found throughout the subtropical and warm temperate valleys of the southern edge of the Great Eurasian Mountain Chain from Greece to China, with a population extending northwards around the Black and Caspian seas, and subfossil remains have been found well to the north, up to the Ural Mountains, as recently as 10,000 years ago.

The belubos has a highly disjunct range that is dependant on montane foothills and deep warm valleys. They have been sighted migrating across cold and often icy passes during summer, which possibly may explain why they have readily spread across the warmer regions north during the current interglacial.

Belubos family structure mainly consists of an old dominant female, her daughters and their mates. These animals live between worlds, dealing with hot steaming tropics and chill montane krummholtz every year in the search for food.

Bruton (Catoblepas migratoris)[]

Large herds of brutons roam across central and eastern Europe, spending the summers near the southern shores of the Baltic Sea or the edge of the Russian taiga and returning south for the winter.

The bruton is the most wide ranging catoblepine. They can be found throughout the open grasslands of Eastern Europe to the plains of central Europe. Brutons have the most extensive osteoderms of all the catoblepines, forming an almost ankylosaurine - or vanguardian - surface. They also are the largest of the catoblepines: mature females routinely reach 8 tons in weight.

Brutons are a force on the grasslands they roam. Huge herds up to a thousand strong can graze entire regions literally down to stubble. This action expands the grasslands greatly; most other megaherbivores prefer to clip up and suck down easily accessible vegetation, but the brutons methodically strip the land of almost anything edible. The herds are known to chop away at whole stands of sapling trees just to fell them for their crowns. The impact they have on the local ecosystem is simply unimaginable in scale.

Yata (Anatobison anatobison) []

The yata is currently the only North American ungulapede. A denizen of the open prairies of Central North America, yatas gather in immense herds, ranging across continental America, from Canada to Mexico, with isolated populations in Alaska’s colder grasslands, the highland plains of the Rockies and Florida’s savannas. The yata seems to have taken the ecological niche previously held in America by torgs, which may be evidence of direct out-competition or maybe an opportunistic replacement after they went extinct, somewhere in the mid-Pleistocene. The massive yata herds are often found in association with the humngo herds, following the giant neohadrosaurs to grass on the new buds left by the devastation of the giants. The yata themselves are a transformative force, having a more selective grazing style than the vacuum-cleaning of the hmungos, affecting thus the grass diversity in an area directly. In areas where hmungos are rarer, the myriads of other herbivores of the plains follow the yata herds instead, and some species benefit from its less catholic diet, as it encourages certain species to grow over others.

EALINAE (Yales and Kirins) []

Often referred to as tricorns, ealines are the most widespread and species of ornithopods in Eurasia (about 50 species). They are distinctive in possessing an enlarged middle toe on the pes with a reduction of the other two toes, a long unicorn-horn whose base is restricted to the frontals. Most are grazers that live in pairs or small to moderate sized herds. Unlike the polygamous catoblepines, most ealide species form stable pair or trio bonds. Not surprisingly, the tricorns exhibit conspicuous external sexual dimorphism. These species seem to originate between the late Miocene to Late Pliocene fossil deposits in Spain and France with the discovery of †Proteale tricornis.

Yale (Eale recticornis) []

The Eurasian yales are quite similiar to their distant cousins, the African saurolopes. These lightweight hadrosaurs are fast gallopers, which live in herds that follow the migratory brutons. Several more yale species are found in the Middle East and India.

Malta Yale (Ealoides malta) []

The Malta yale is a diminutive dwarf that shares an ancestry with the mainland yale. The malta yale is quite small, less than 18 kilos for adult males. They have fairly short stout limbs well suited for clambering up rocky faces, where they might meet a spelk. Reproduction tends to quite long. The life long male/female pair generally breeds once every two years. There are few threats to these animals aside from avisaurs and careless sauropods.

Kirin (Kirin chilin) []

Kirins are the yales of eastern Asia. These antelope-like ealinids live in herds of about 10-30 individuals and ruled by an old male. The long, straight central horn of the kirin is a formidable weapon, but mostly used only for intimidation between males or against predators. Only kirin males have a long, forward-pointing horn; the female's horn is shorter and points straight up from the skull. The horn structure is remarkably similar to the giant African elumbe, though it seems to be mere convergence.

Ki-lin (Kirin rex) []

Ealines are much younger residents of Japan than the baku, arriving in Japan during the Pleistocene. Although more species did exist, the ravages of the Ice Ages wiped out all but two species, ki-lin (Kirin rex) and the qilin (Kirin opibus). The more cold-tolerant of the two, the ki-lin ranges from southern Hokkaido to central Honshu, where it interlaps with the larger qilin. They seem to live in small family herds of up to five members.

Qilin (Kirin opibus) []

The larger of the two Japanese species of kirin, the qilin can be found in the heavily forested areas of Japan, ranging southward from central Honshu down to the southern tip of Kyushu. As of now, little else is known about this rare and enigmatic animal.